Researchers have created a method for haptic communications that lets users receive messages through the skin on the forearm by learning to interpret signals such as a buzzing sensation.

Hong Tan, founder and director of the Haptic Interface Research Laboratory at Purdue University, says that, while the research lends itself to use by hearing-impaired and visually impaired users, the method could work well for any number of possible uses.

“We are collaborating with Facebook through the company’s Sponsored Academic Research Agreement. Facebook is interested in developing new platforms for communication and the haptic research we are doing has been promising,” she says.

“I’m excited about this… imagine a future where you’re able to wear a sleeve that discreetly sends messages to you—through your skin—in times when it may be inconvenient to look at a text message,” Tan says. “I’m really hoping this takes off as a general idea for a new way to communicate. When that happens, the hearing-impaired, the visually-impaired, everyone can benefit.”

How it works

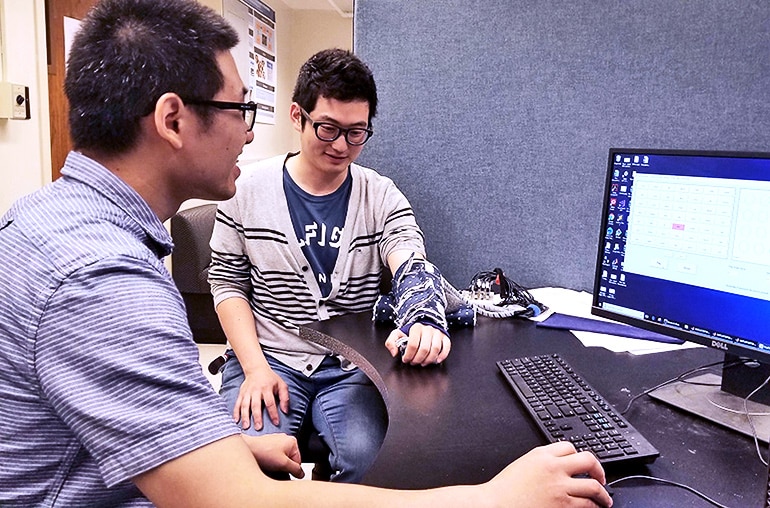

In the study, subjects used a material cuff encircling the forearm from the wrist to below the elbow. The instrument, wrapped around the test subject’s non-dominant arm, featured 24 tactors that, when stimulated, emitted a vibration against the skin, changing quality and position in the process.

Tan says the researchers mapped the 39 phonemes (units of sound in a language that distinguish one word from another) in the English language using signals from specific tactors. They made sounds of consonants such as K, P, and T stationary sensations on different areas of the arm and vowels indicated by stimulations that moved up, down, or around the forearm.

“We used anything that can help you establish the mapping and recognize and memorize it,” Tan says. “This is based on a better understanding of how to transmit information through the sense of touch in a more intuitive and effective manner.”

Twelve subjects learned haptic symbols through the phoneme-based method at a schedule of 100 words in 100 minutes for the research, while 12 others learned using a word-based system with the haptic signals on their arm.

Research results show the phonemes worked better than a word-based approach by providing a more consistent path for user learning in a shorter period of time. Performance levels varied greatly among the test subjects for each method, but with the phoneme-based approach at least half could perform at 80 percent accuracy while two subjects reached 90 percent accuracy.

Learning is key

Tan says using phonemes was more efficient compared to letters, noting there are less phonemes in a word compared with the number of letters.

She says the reasoning behind the project is the thought that there are many ways to encode speech into feelings. The project goal is to demonstrate one way that actually works.

Keyboard tech speeds browsing for blind internet users

“For this research, the learning progress is one of the key things,” Tan says. “With this, not only do we have a system that works, but we’re able to train people within hours rather than months or even years.”

For the study, the researchers developed a concentrated, intense training regimen where the test subjects worked for about 10 minutes a day. The researchers then tested the participants on their progress.

“It is more efficient than if they sit here for three hours to study,” Tan says. “You can’t keep good concentration for that long.”

“People who are hearing-impaired may be motivated to spend additional time to training themselves, but the general public probably doesn’t have the patience,” she adds.

The researchers presented their work at the EuroHaptics 2018 conference in Pisa, Italy. Facebook Inc. funded the research.

Source: Purdue University