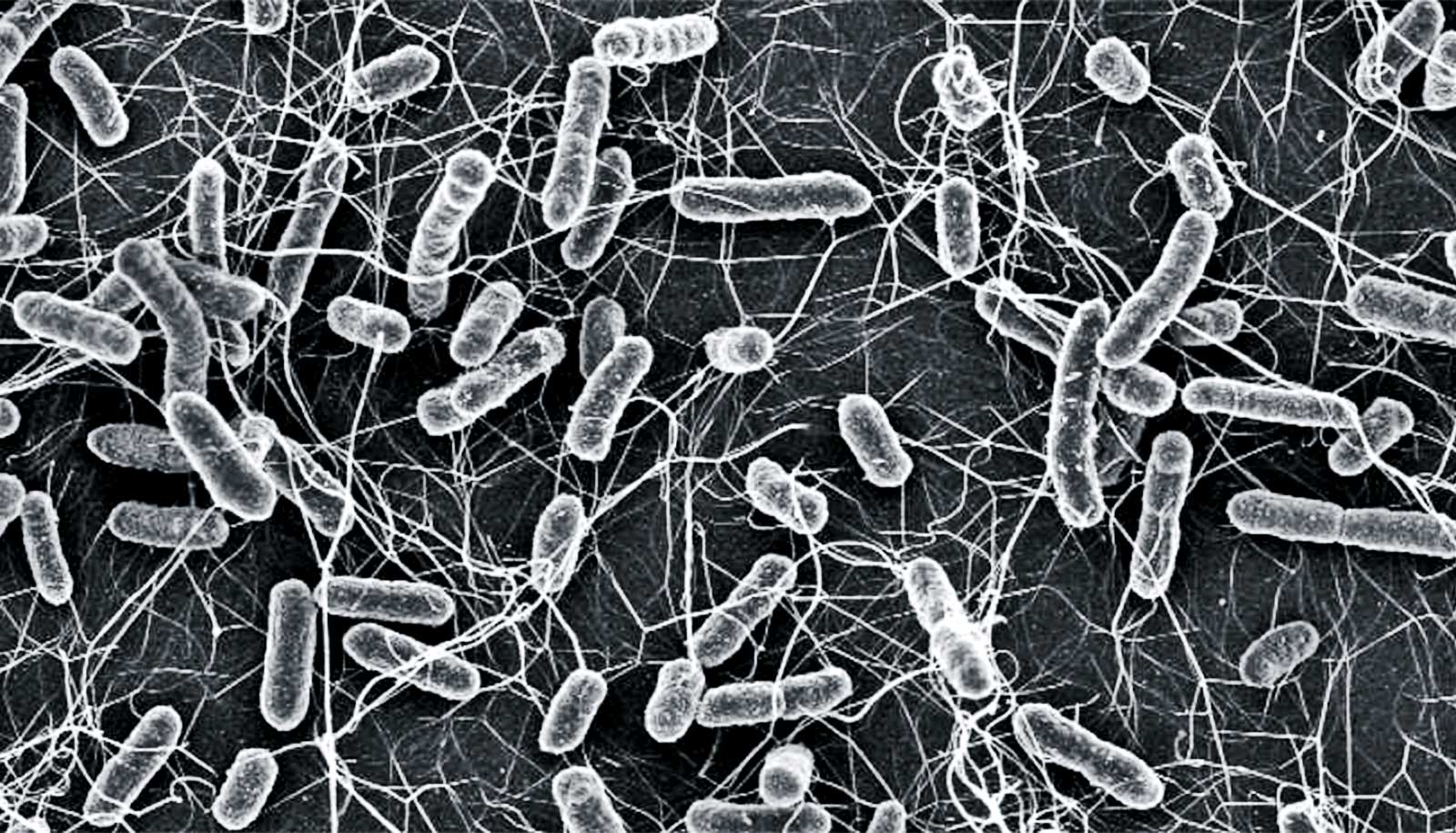

Antibiotics change the composition and metabolism of gut bacteria in mice, and food can make things better or worse, according to new research.

Antibiotics save countless lives each year from harmful bacterial infections—but the community of beneficial bacteria that live in human intestines, known as the microbiome, frequently suffers collateral damage.

Peter Belenky, an assistant professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at Brown University, studies ways to minimize this side effect, which can lead to C. diff infections and other life-threatening imbalances in the microbiome.

The new findings are a step, Belenky says, toward helping humans to better tolerate antibiotic treatment.

“Doctors now know that each antibiotic prescription has the potential to lead to some very harmful microbiome-related health outcomes, but they do not have reliable tools to protect this critical community while also treating deadly infections,” Belenky says. “The goal of my lab is to identify new ways to protect the microbiome, which may alleviate some of the worst antibiotic side effects.”

Why gut bacteria are important

The gut microbiome is an ecosystem comprising trillions of bacteria that have specifically coevolved with its host. This community helps the host in many ways such as breaking down dietary fiber and assisting in the maintenance of overall intestinal health—by ensuring the intestinal cells form a tight barrier and competing for resources with harmful bacteria, Belenky says.

Lead study author Damien Cabral, a doctoral student in the pathobiology program, treated three groups of mice with different antibiotics, then monitored how the composition of bacteria in the mouse guts changed and how the bacteria adapted at a metabolic level after antibiotic treatment.

Amoxicillin, commonly used to treat ear infections and strep throat, drastically reduced the kinds of bacteria present in the gut and changed the genes used by the remaining bacteria. The researchers also studied ciprofloxacin, used to treat urinary tract infections and typhoid fever, and doxycycline, often applied in treating Lyme disease and sinus infections. The changes associated with those drugs were less pronounced.

One type of potentially beneficial bacteria common in the human gut, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, actually flourished after amoxicillin treatment. Following treatment, this bacteria increased its reliance on enzymes that digest fiber, a change that appears to both allow it to thrive in the changed ecosystem and somehow protected it from the antibiotic, Belenky says.

In general, the bacteria decreased the use of genes involved in normal growth, such as making new proteins and DNA. At the same time, they also increased use of genes critical for stress resistance.

Protection via food?

Interestingly, Belenky’s team found that adding glucose to a mouse’s diet—which is typically high in fiber and low in simple sugars—increased Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron’s susceptibility to amoxicillin. This hints that diet can protect some beneficial gut bacteria from the ravages of antibiotics.

“For a long time we’ve known that antibiotics impact the microbiome,” Belenky says. “We have also known that diet impacts the microbiome. This is the first paper that brings those two facts together.”

Belenky cautions that the study involved in rodents, and there is still much to learn about the interplay among host diet, microbiome metabolism, and vulnerability to different antibiotics.

“Now that we know diet is important for bacterial susceptibility to antibiotics, we can ask new questions about which nutrients are have an impact and see if we can predict the influence of different diets,” he says.

Belenky’s team is exploring how different kinds of dietary fibers impact how the microbiome changes after antibiotic treatment, and how diabetes might impact the microbiome’s metabolic environment and antibiotic susceptibility.

Additional researchers are from Brown and the Mayo Clinic. The Department of Defense, National Science Foundation, and National Institutes of Health COBREs supported the research.

Source: Brown University