A new computational model could offer a way to control Guinea worm disease, which was almost eradicated in humans but became prevalent in dogs a few years ago.

The disease’s prevalence in dogs means it could cross back over into human populations.

“We’ve been developing models of disease in human populations for a long time. We think that developing models for these reservoir species is increasingly important,” says Julie Swann, professor of the industrial and systems engineering department at North Carolina State University and coauthor of a study on the work.

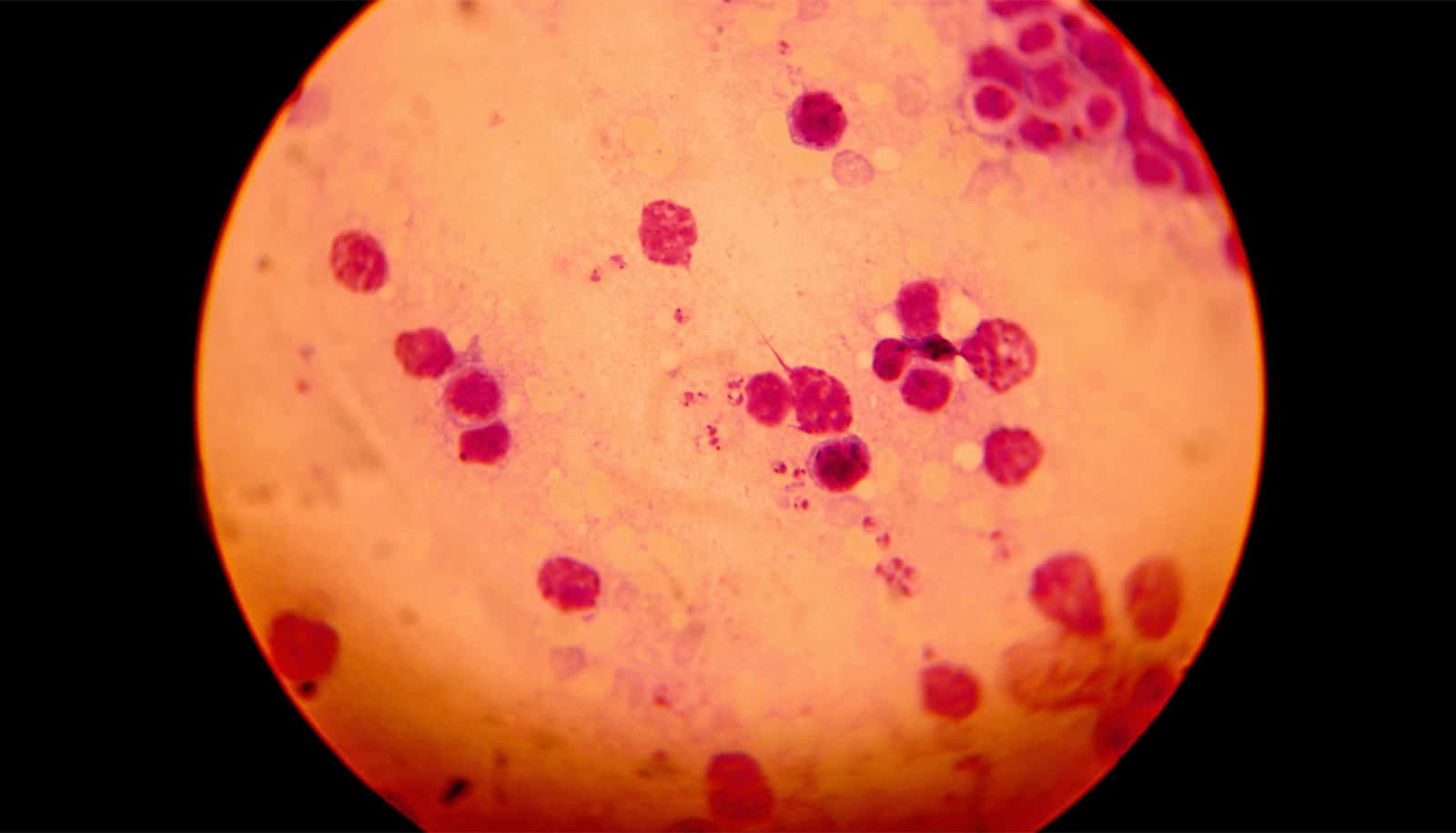

As recently as the mid-1980s, Guinea worm disease (also known as dracunculiasis or GWD) affected millions of people each year. A parasitic worm causes the disease, which leads to fever, swelling, and pain. The disease can be disabling and can also lead to secondary infections.

Due to a concerted public health effort, the number of reported Guinea worm disease cases had dropped to fewer than 30 by 2018. More than half of those cases were in Chad, in north-central Africa.

However, observers reported an increase in the number of cases of Guinea worm disease in dogs—with more than 1,000 confirmed canine cases in Chad. This raises concerns that dogs can serve as a reservoir species for Guinea worm disease. In other words, the parasite responsible for Guinea worm disease may thrive in the canine population and, eventually, could become prevalent again among humans.

To address this concern, researchers are developing models to understand how the disease spreads in the dog population of Chad—and more importantly, how to stop it.

The new paper in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine & Hygiene focuses on a model that essentially serves as a foundation for the work moving forward. The model establishes the parameters of the disease for dogs in Chad, and helps observers determine which variables are most important for controlling the disease.

For example, the model reflects the well-established seasonal nature of the disease—but also lets us know just how effectively a single dog can transmit the disease: in the month when the disease is at “peak infectivity,” an infected dog can infect an average of 3.6 other dogs.

The bad news is that the model makes clear that there are multiple variables at play in terms of determining the likelihood of disease transmission. But even that is a concrete step forward, as it helps researchers better define the problem.

“This work makes clear that eradicating Guinea worm disease is going to take a concerted effort; it’s not something that can be knocked out in a couple of years,” Swann says. “We’re currently developing regionally-specific models for different parts of Chad—which is essential, given the size and diversity of the country. These models will help us identify the most effective interventions for decreasing the prevalence of Guinea worm disease in dogs and, ultimately, help us wipe this disease out for good among humans.”

Additional coauthors are from Georgia Tech, the Carter Center, and NC State.

Source: NC State