The moral language in Greta Thunberg’s climate change speech at the United Nations may have added to its impact, researchers report.

The 16-year-old accused world leaders of neglecting their duty and foisting the problems one generation created onto the backs of another—today’s youth. Her statement was certainly morally charged, but how exactly did the content of Thunberg’s message change the effect it may have had?

To answer that question, Rene Weber, director of the Media Neuroscience Lab at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and graduate student Frederic Hopp used a system Weber developed in his lab that analyzes real-world moral framing and moral conflict in messages.

“There is mounting evidence that environmental attitudes are firmly rooted in humans’ moral intuitions,” says Weber, who is also a professor in the communication department. “As a result, successfully informing citizens about the consequences of climate change and calling for action will require activists and policy makers to frame their messages according to their audiences’ moral sensitivities.”

Greta Thunberg’s speech and morality

MoNa, the Moral Narrative Analyzer, takes advantage of computer algorithms, large-scale text mining, and evaluations from a large, diverse group of humans to decode the innate moral framing within different texts.

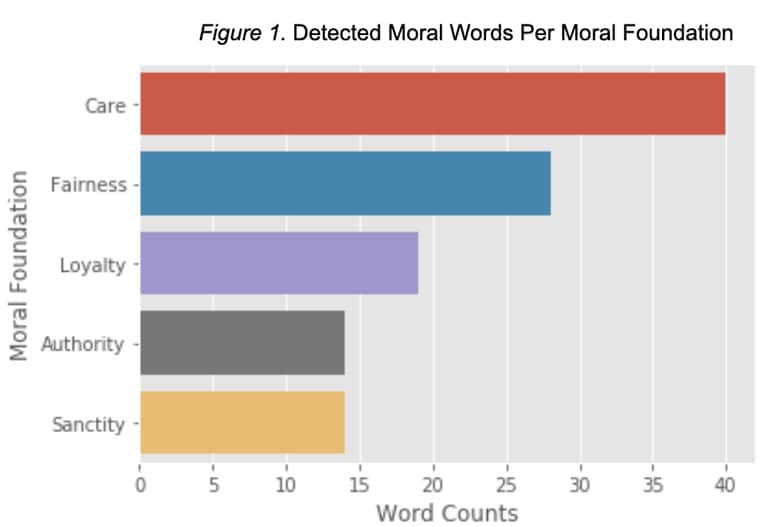

According to Weber, all moral systems humans have developed touch on five fundamental categories.

- Care vs. Harm

- Fairness vs. Cheating

- Loyalty vs. Betrayal

- Authority vs. Subversion

- Purity vs. Desecration

Weber and Hopp were curious about the representation of these categories in Thunberg’s speech, so they used MoNA to decipher how she framed her message.

In line with Thunberg’s strong appeal to the harm and unfairness of the current climate crisis, MoNA identified care/harm and fairness/cheating as the most dominant moral frames in her speech.

“Research has shown that liberals are especially sensitive to violations of care and fairness,” Weber explains, “whereas conservative individuals tend to place greater emphasis on violations of loyalty, authority, sanctity.” In this light, climate messages that stress the notions of care/harm and fairness/cheating will likely prove more persuasive among liberal audiences.

However, Weber continues, Thunberg also framed climate change as a betrayal of political leaders and older generations against the world’s youth, who will have to adapt to and address a crisis they inherited due to the recalcitrance and apathy of those currently in power.

Positive or negative?

Weber and Hopp also used MoNA to analyze the sentiment of the speech’s moral content—whether it was positive or negative. They found some intriguing patterns.

Thunberg relies on more negative words when referring to issues of care and authority, they note, potentially highlighting the violation of these moral foundations by policy leaders. In contrast, she appears to use more positive language when referring to topics of fairness and loyalty, potentially indicating her hope for future adherence to these foundations by world leaders.

For example, stating that “we need to care about the health of our climate” reflects a call for virtue in the care category, whereas stating that “we fail to adhere to our plans and agreements” suggests a vice in the loyalty foundation.

Weber and Hopp express caution regarding the results of their analysis. “Thunberg is relying on words that fall into categories of moral foundations,” Hopp says, but he adds that the broader effects this may have fall outside the scope of their relatively quick analysis. However, with more data, MoNA can help researchers and other interested groups to analyze real-world reactions—like activism, donations, and changes in behavior—to speeches like Greta’s as well as other persuasive language.

“I believe this quick analysis demonstrates MoNA’s capability to extract moral frames from real-world text with high reliability and validity,” Weber says.

Source: UC Santa Barbara