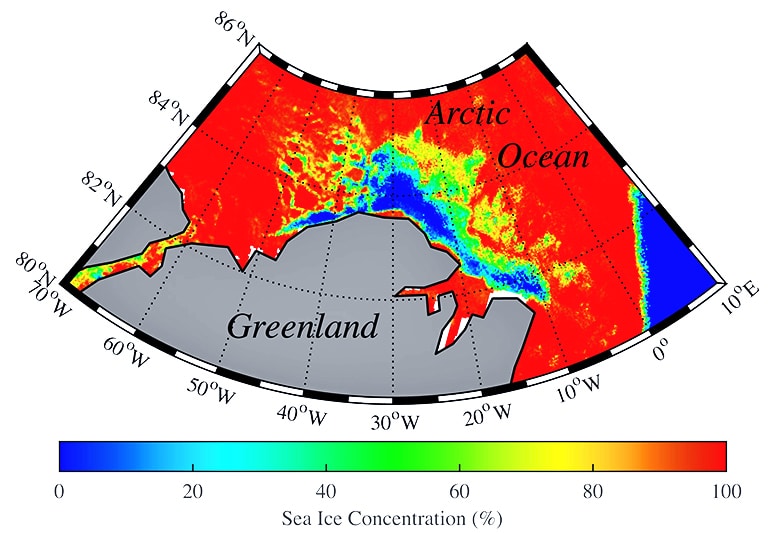

A new analysis shows that odd winds, rather than simple global warming, were to blame for a vast expanse of open water that appeared in the sea ice above Greenland in February 2018.

Although last winter did see unusually warm temperature spikes in the Arctic, researchers say the cause for the big pool of open water in the middle of the ice—known as a polynya—was strong surface winds triggered by a dramatic warming in Earth’s upper atmosphere, known as a “sudden stratospheric warming.” The region normally has sea ice well into the spring.

“During these events, temperatures in the stratosphere—about 30 kilometers above ground level—can warm by 10 or 15 degrees Celsius in just a few days,” says Kent Moore of the University of Toronto Mississauga and lead author of the paper, which appears in Geophysical Research Letters.

Winds, not thinning ice

The sudden warming of 18 to 27 degrees Fahrenheit at some 18 miles elevation shifts air pressure and therefore circulation patterns. In February 2018, it caused winds from Siberia to blow cold air into Northern Europe, creating a weather system that became known as the “Beast from the East.” That same weather pattern drew warmer air north up the east coast of Greenland, and generated persistent strong winds.

“This [wind pattern] lasted a week, and these were the warmest temperatures and strongest winds observed in north Greenland since observations began in the 1960s,” Moore says. “Winds were close to hurricane force and temperatures were above freezing. Once we got that piece of the puzzle, we realized it could be wind rather than warmth that caused the polynya.”

Researchers used the Pan-Arctic Ice Ocean Modeling and Assimilation System (PIOMAS) tool, developed at the University of Washington, to reconstruct sea ice conditions in the Arctic Ocean.

“Letting your intuition guide your hypothesis, then letting yourself be convinced otherwise—that’s science.”

They ran a simulation with the atmospheric conditions of 2018 but with thicker sea ice that was present in the Arctic in 1979, to see if thinner sea ice due to climate change caused the open water to appear. The patch of open water in that area was unprecedented in observations and lasted about three weeks, from mid-February through the first week of March.

“We used to ask the question hypothetically: What would have happened if the ice had been as thick as in 1979?” says coauthor Axel Schweiger, a polar scientist at the University of Washington’s Applied Physics Laboratory. “Now, we simulate it. The answer was that the thinning of the ice didn’t matter much, but strong winds were responsible.”

75% sea ice loss

The findings surprised Schweiger, a longtime sea ice researcher. He thought thinning ice would be the decisive factor.

“But when we looked closer, it wasn’t. Letting your intuition guide your hypothesis, then letting yourself be convinced otherwise—that’s science,” he says.

Scientists commonly use PIOMAS to gauge the total volume of Arctic sea ice in a given month. Overall, it shows the minimum volume of Arctic sea ice, reached in September, has recovered slightly from its all-time low in 2012, but is still following a long-term decline over the past four decades.

“We’ve lost about half of the extent, we’ve lost half of the thickness, and if you multiply these two things, we’ve lost 75 percent of the September sea ice,” Schweiger recently told the Washington Post.

Source: University of Washington