If the average fertility rate in 1970 still held true, the global population would be 14 billion, or twice what it is today. So what’s behind the change? Choices by women, according to a new report on global fertility rates.

This is, in fact, one of the most important but least recognized achievements in human history, says Peter McDonald, professor of demography at the University of Melbourne and chief investigator of the new report from the United Nations Population Fund, the State of World Population for 2018.

Falling fertility rates

The report shows fertility rates first declined in France from the first half of the 19th century.

Despite strong opposition from governments and established religions, the birth rate began to fall in English-speaking countries and Nordic countries from around 1870. Over the following 50 years, other European countries followed.

In Australia, among married women, the peak number of children that they had over their lifetimes fell from eight for those women born between 1851 and 1856, to four for those born just 10 years later—between 1861 and 1866.

Previous research shows that the Australian decline was associated with the agency of women increasing through the universal education of girls. This meant that women, rather than men, were putting themselves in charge of fertility decision-making, McDonald says.

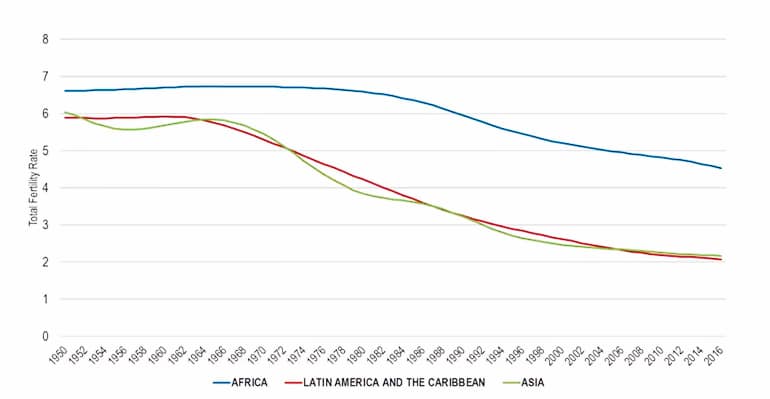

From the 1970s onward, the birth rate also began to fall throughout Asia and Latin America. In Asia, this was often the result of government sponsored family-planning programs that in some places went beyond the bounds of human rights in forcing women to accept some methods of contraception.

The government was also involved in some countries in Latin America but generally less forcefully. This correspondence in the trends between these two very different parts of the world suggests the more draconian approaches in some parts of Asia were unnecessary, McDonald says.

In Africa, fertility fell first in the countries of Northern and Southern Africa, followed more recently by East African countries, like Rwanda and Kenya. While fertility remains high in West and Central African countries, a decline is underway in almost all these countries as women’s education levels increase.

Emerging issues

The importance of the link between women’s education and the decline in birth rate is an obvious one, McDonald says. It can be seen in the correlation between the Total Fertility Rate, which is the total number of children born or likely to be born to a woman in her lifetime, and the education level of women aged between 25 and 29 across many countries between 2010 and 2014. It was extremely high at -0.87.

But now, there are new issues emerging, McDonald says.

Although fertility has stabilized at levels above two children per woman in some countries, in the countries of Central Asia, the fertility rate (which had been close to two) has risen to around three children per woman. This is linked to the fact that many women there are having the number of children they want to have.

The future direction of fertility is also unclear in countries where the fertility rate has only recently fallen to around the replacement level—this is the point at which a population exactly replaces itself from one generation to the next, without migration.

These countries are mostly in Latin America and South Asia; but also in countries where Islam is the main religion. Some of these countries are concerned that their fertility rates may fall to the very low levels—that is below 1.5 births per woman—which are becoming the norm in some European and East Asian countries.

Reproductive rights

There’s also an interesting split in fertility rates happening in Europe, English-speaking countries, and the East Asian countries. Current rates are very low in the countries of Southern and Eastern Europe, the eastern part of Western Europe and in East Asia.

But in Northern Europe, the western part of Western Europe and in the English-speaking countries it sits higher, between 1.6 and 2 children per woman.

This split is attributed to the extent to which some governments and employers provide support for families with children, this includes policies that support the combination of work and children, McDonald says.

But, the big picture, what’s important is that reproductive rights are extended to all women and men, he says.

Each country needs to define the mix of services and resources it requires to uphold reproductive rights for all citizens, ensuring that no one is left behind, and to dismantle social, economic, institutional, and geographic obstacles that prevent couples and individuals from deciding freely and responsibly the number and timing of pregnancies, McDonald says.

Source: University of Melbourne