George Orwell not only vocally advocated human rights but also attempted, in the years between writing Animal Farm and 1984, to found an international body that would defend human rights in the tense aftermath of World War II, according to a recent discovery.

Orwell’s partners in this project were also renowned: the philosopher Bertrand Russell and the novelist Arthur Koestler.

In his new book, George Orwell Illustrated (Haymarket Books, 2018), David N. Smith offers an encompassing look at Orwell’s life, writings, and worldview, with illustrations by artist Mike Mosher. Smith, a professor in the sociology department at the University of Kansas, also presents and discusses a previously unpublished document that he found in an obscure archive: a manifesto that Orwell wrote in 1946 in dialogue with Koestler and Russell.

Smith says that two things stood out regarding the manifesto. To begin with, Orwell seldom wrote with coauthors. Second, the manifesto was written for a directly constructive purpose.

“In his essays, Orwell was mainly a cultural commentator,” Smith says, “but in this document, with Russell and Koestler, he called for a new international organization, which they themselves planned to organize.”

Finding the manifesto

Orwell is best known, of course, for the dystopia 1984, which Smith first discussed in Orwell for Beginners—an early version of George Orwell Illustrated that, not coincidentally, was published in 1984.

Interest in Orwell has grown steadily since he succumbed to tuberculosis at the age of 46 in 1950.

“So much attention has been lavished on him,” Smith says, “that Orwell is clearly among the 20th century’s most influential writers.”

Renewed interest in 1984 soars, Smith says, whenever government deceit and overreach come to light, as they were in Edward Snowden’s revelations about National Security Agency surveillance in 2013 and, early in Donald Trump’s presidency, when talk of “alternative facts” and Russian intervention in the 2016 election became commonplace.

Smith discovered Orwell’s manifesto after finding, in the final volume of Orwell’s complete works published in 1998, that Orwell had exchanged friendly letters with Ruth Fischer just months before 1984 appeared. In the 1920s, Fischer had been the general secretary of the German Communist Party, but since then she had been an intransigent opponent of the Soviet Union and German communism.

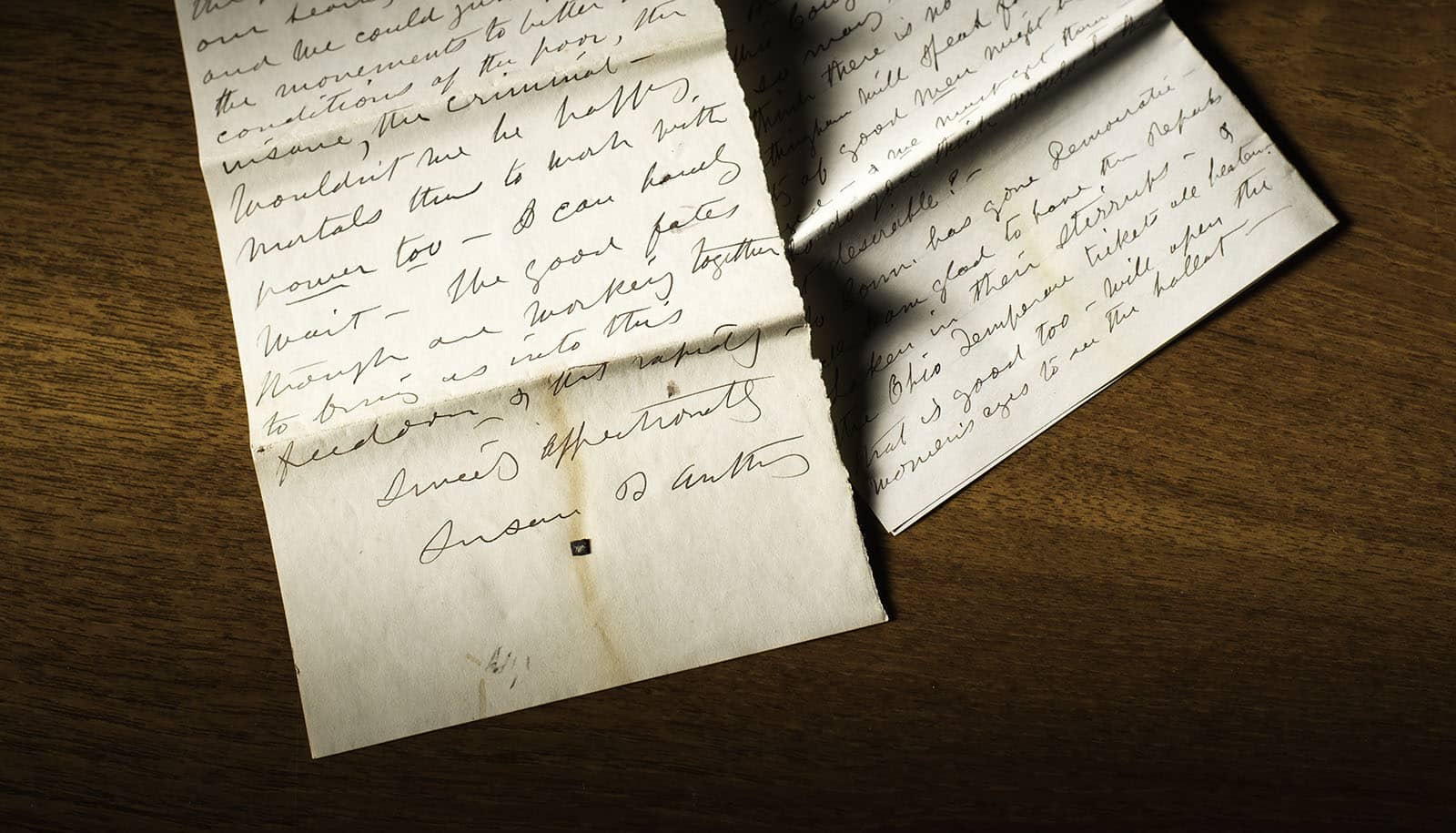

In 1948, Fischer published a critical exposé of Stalin’s betrayal of the German left, which Orwell read and admired. That led to their correspondence, which piqued Smith’s curiosity and led him to rummage through Fischer’s archive at Harvard. There he found the human rights manifesto, which Fischer had received from Koestler in 1949.

Promoting peace and democracy

Orwell wrote the manifesto after spending Christmas in Wales in 1945 with Koestler and his family. It was during that holiday that Orwell and Koestler decided to form a new group that would lobby for the ever-deeper democratization of society.

World War II had just ended, and though the Cold War had not yet begun, tensions between the United States and Soviet Union had begun to rise. Orwell and Koestler feared that even harsher dictatorships and deadlier wars would be the grave outcome of these tensions—not least, Smith says, because atomic weapons had just been used for the first time in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

“Orwell and Koestler felt that it was in everyone’s interest to promote peace and democracy, and they believed they had a small window of opportunity to influence public opinion before the two sides split apart and perhaps started fighting,” Smith says.

“That was the hope that led them to call for a new international organization that would press not only for human rights in the conventional sense but also ‘equality of chance for every newborn citizen’ and unfettered access to ideas and opinions, across every border.”

Divided goals

Ultimately, the project faltered, as Koestler and Russell became more intensely anti-Soviet, while Orwell wanted to maintain a posture of neutrality.

“Orwell was critical of every major power, but he wanted their new organization to be even-handed and neutral, defending human rights everywhere,” Smith says.

When that hope was dashed, Orwell moved to an island near Scotland, where he turned his concern about dictatorship and atomic war into “1984.” Although many of his dystopian fears ultimately proved to be more than justified, Orwell’s aim in “1984” was to sound an alarm—with the hope, Smith says, that dystopia could be forestalled.

Now, Smith says, he sees parallels to Orwell’s human rights views in some of the late-breaking developments in today’s United Nations. Most notable, he says, is Philip Alston’s reporting as the UN’s special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, which, in several ways, resembles Orwell’s manifesto.

Overall, Orwell’s manifesto puts the famed author in a new light.

“Orwell isn’t usually pictured as someone who wanted to have a direct constructive impact on world affairs,” Smith says. “But he did have that wish, and the manifesto makes it clear that he saw his literary work, his novels and essays, as part of that larger mission.”

Source: University of Kansas