A new study shows just how much of a psychological toll the murder of George Floyd took on people in America, particularly among Black Americans.

Following the murder of Floyd, an unarmed Black man killed by a white police officer, more than one-third of Americans reported feelings of anger and sadness in the week after his death.

Black Americans experienced grief at a much higher rate: Nearly one-half of all Black Americans reported feeling angry or sad in the wake of Floyd’s death, and nearly one million more Black Americans screened positive for depression, according to a new analysis of US Gallup and census data.

“People realize ‘that could have been me or a member of my family.’ It touches the emotional core of who we are.”

“Coming out of the COVID-19 crisis, national surveys were tracking how the mental health of the population was developing. When George Floyd was murdered, these data collections caught the dramatic psychological impact, giving us a glimpse of how this collective moral injury impacted emotions and mental health,” says Johannes Eichstaedt, an assistant professor (research) of psychology at Stanford University and lead author of the new paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

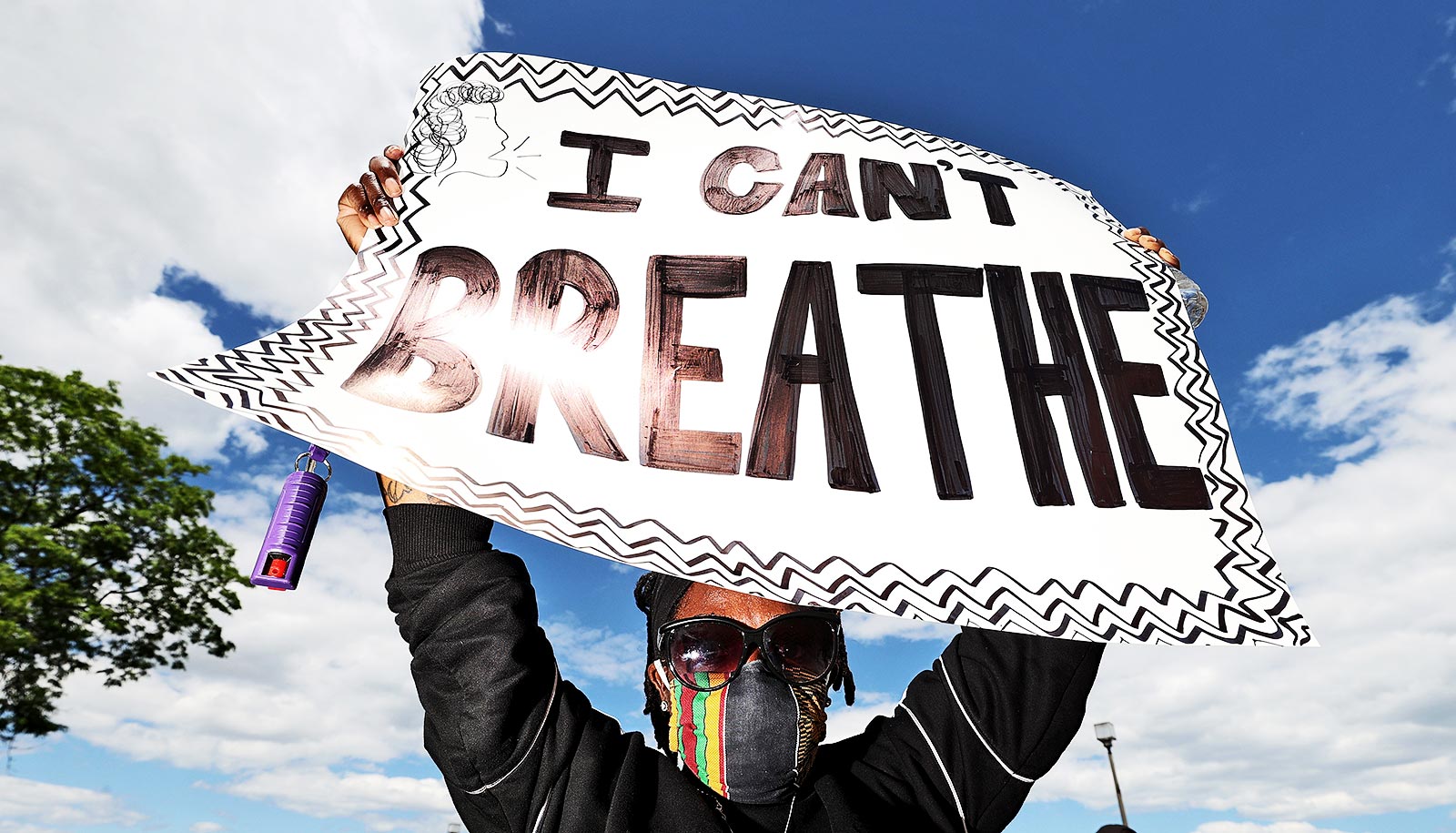

In the weeks after Floyd’s murder on May 25, 2020, protests erupted across the country after millions of people watched the chilling video footage of his murder. His violent death, along with the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and other victims of police brutality, galvanized a nationwide movement—the largest in the country’s history—about the many ways structural racism and bias is embedded in American lives.

“To see that movement manifested at the psychological level is powerful, showing that people were not only socially invested in change, but that they were emotionally invested as well,” says coauthor Steven O. Roberts, an assistant professor of psychology.

Anger and sadness

To examine the rates of anger and sadness following Floyd’s murder, researchers used the Gallup COVID-19 Panel survey from four weeks before and after his death.

Data showed that immediately after Floyd’s death, feelings of anger increased by about half in the population: Roughly 38% of Americans said they experienced anger. Sadness increased about a third, with 38% also reporting feelings of loss, despair, and grief.

Feelings of anger and sadness were particularly acute in the Black community in the wake of Floyd’s death.

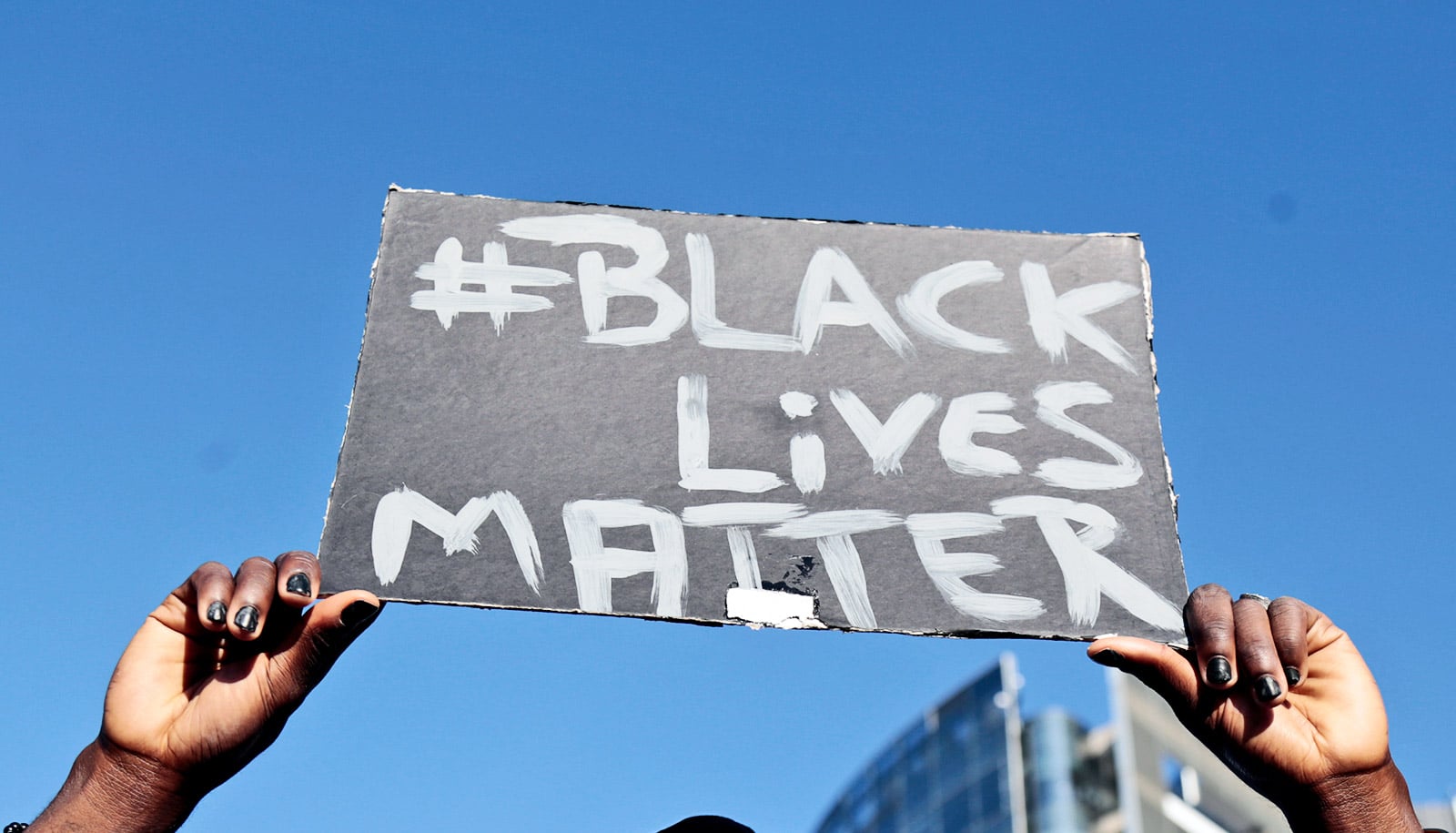

“In order to have a more equitable society in which Black Lives Matter, we must acknowledge that the mental lives of Black Americans matter as well.”

Nearly 1 in 2 Black Americans reported feelings of anger (48%), representing a 2.1-fold increase from the week before. Sadness also soared to 47% of Black Americans reporting feelings of loss, despair, and grief. Among white Americans it was about 1 in 3: Some 34% said they experienced anger and 36% sadness.

“Seeing a member of one’s group killed engenders a feeling of threat and vulnerability,” says Eichstaedt, who also directs Stanford’s Computational Psychology and Well-Being Lab. “People realize ‘that could have been me or a member of my family.’ It touches the emotional core of who we are.”

These spikes are the largest Gallup has observed since 2009, when the public opinion firm began tracking emotions, the researchers say.

“Data from a representative Gallup survey of Americans suggest that anger and sadness in the US population increased to unprecedented levels after his death,” they wrote in the paper. While Gallup did not consistently measure anger and sadness during the previous decade, the highest levels of anger and sadness previously recorded occurred after the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, with 16% reporting feelings of anger and 22% sadness—less than after Floyd’s death reported here.

The researchers also found that when compared to other states, depression and anxiety were higher in Minneapolis, Minnesota, where Floyd’s murder occurred. This finding is consistent with previous scholarship that showed that location matters: the traumatic impact of racial violence and police brutality is larger in the communities in which they occur.

‘Racism gets under the skin, literally’

The researchers also wanted to examine how people’s mental health may have suffered. During the pandemic, rates of depression and anxiety had increased in the population—but the murder of George Floyd added additional mental health burden, particularly for Black Americans, the researchers found.

In their analysis of US Census Household Pulse data gathered in the five weeks before and the week after Floyd’s death, the researchers found that among Black Americans, depression increased 3.2%: 26.7% to 29.9%. For white Americans, it increased 1.2%.

The researchers estimate that for Black Americans, this 2% difference in increase is equivalent to an additional 900,000 individuals screening positive for depression. The researchers estimate that these additional depression screens are each associated with three to seven days of mental unhealth, thus translating to between 2.7 and 6.3 million additional mentally unhealthy days among Black Americans.

For the researchers , the racial disparities revealed in these data show the disproportionate burden that witnessing police violence bears on the Black community.

Previous research has shown that police killings of unarmed Black Americans can be a vicariously traumatizing experience for other Black Americans. Eichstaedt and Roberts’ study confirms the unevenness those spillover effects have in American society.

“Racism gets under the skin, literally,” says Roberts, who also directs the Social Concepts Lab at Stanford. “Not only are Black Americans at increased risk of encountering racial discrimination in the real world—including police brutality—they are also at increased risk of carrying around the psychological burden of that unfortunate reality.”

That psychological burden can often translate into physical ones. Trauma has been shown to have damaging effects on people’s physical health, including an increased risk of heart disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, and obesity, among other effects, the researchers note in the paper.

“In order to have a more equitable society in which Black Lives Matter, we must acknowledge that the mental lives of Black Americans matter as well,” the scholars write.

The death of George Floyd also occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic that saw Black and brown communities shouldering a disproportionate burden of the disease. Floyd’s death brought on a new level of fatigue, Roberts says.

“We need to understand and appreciate that Black Americans—in addition to dealing with the pandemic and work and family responsibilities—have had to carry the weight of George Floyd’s murder,” he says. “Being a Black American necessitates strength and perseverance, and that was especially true in 2020.”

Additional coauthors are from the University of Pennsylvania and Stanford.

Source: Stanford University