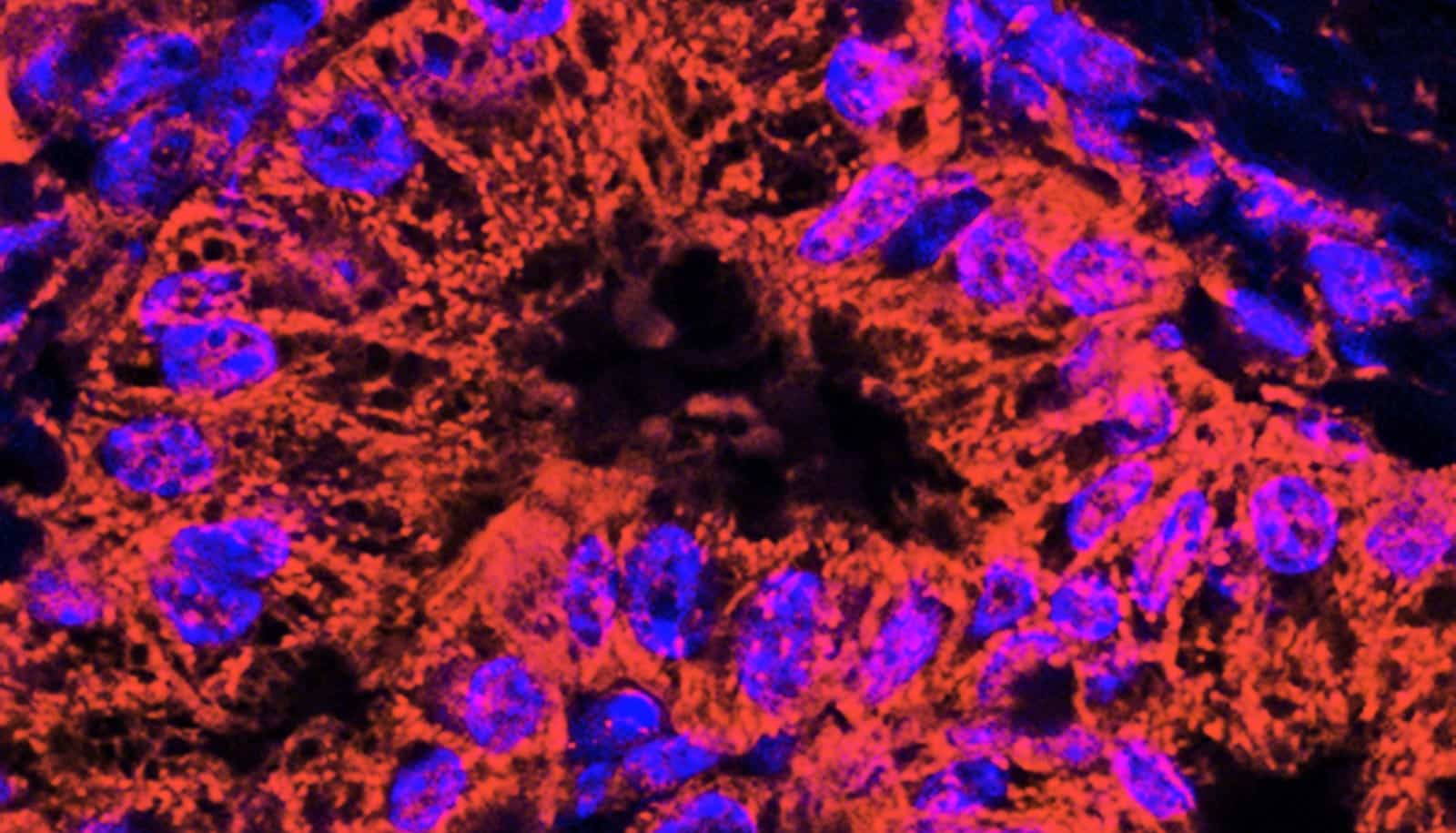

Researchers have successfully shown that a new genetic test can, with high sensitivity, determine which pancreatic cysts are most likely to be associated with an aggressive form of pancreatic cancer.

The successful results are a critical step toward a precision medicine approach to detecting and treating pancreatic cancer, which has one of the lowest survival rates of all cancers.

“This rapid, sensitive test will be useful in guiding physicians on which patients would most benefit from surgery.”

Medical scans increasingly detect pancreatic cysts—small pockets of fluid in the pancreas—by happenstance. For the most part, the cysts are benign. But because some can progress to pancreatic cancer, doctors must determine whether it is surgically necessary to remove the cysts.

“On the one hand, you never want to subject a patient to unneeded surgery. But survival rates for pancreatic cancer are much better if it is caught before symptoms arise, so you also don’t want to ignore an early warning sign,” says lead author Aatur D. Singhi, a surgical pathologist in the anatomic pathology division of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. “This rapid, sensitive test will be useful in guiding physicians on which patients would most benefit from surgery.”

Singhi and his team developed PancreaSeq, which requires the removal of a small amount of fluid from the cyst to test for 10 different tumor genes associated with pancreatic cancer. It is the first such prospective study, testing pancreatic cysts before surgery, rather than analyzing cysts after surgery as had been done by previous efforts.

The study is also the first to evaluate a test that employed a more sensitive genetic sequencing method called next-generation sequencing and the first to be performed in a certified and accredited clinical laboratory as opposed to a research setting.

“This was important to us,” says Singhi. “If PancreaSeq is going to be used to make clinical decisions, then it needed to be evaluated in a clinical setting in real time, with all the pressures that go with a clinical diagnosis.”

In this analysis phase, the test was not intended to be used as the sole factor in determining whether to remove the cyst or not, so doctors relied on current guidelines when deciding on a course of treatment. The researchers tested a total of 595 patients, and the team followed up with analysis of surgically removed cysts, available for 102 of the patients, to evaluate the accuracy of the test.

To screen for pancreatic cancer, take a selfie

The study showed that with 100 percent accuracy, PancreaSeq correctly classified every patient in the evaluation group who had intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN)—a common precursor to pancreatic cancer—based on the presence of mutations in two genes, KRAS and GNAS. Furthermore, by analyzing mutations in three additional genes, the test also identified the cysts that would eventually progress to being cancerous lesions, also with 100 percent accuracy.

The test was less accurate for the less prevalent pancreatic cyst type called mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN)—catching only 30 percent of the cases. Importantly, PancreaSeq did not identify any false positives in either cyst type, making it a highly specific test.

The researchers note that the results could be biased by choice of which patients had their cysts surgically removed, but plan to monitor those who did not have their cysts removed to continue evaluation of the test’s reliability.

An improved version of PancreaSeq that incorporates additional tumor genes associated with pancreatic cancer currently is undergoing rigorous clinical testing, according to Singhi. In the future, the team notes, clinical guidelines will need to be revisited to explore incorporating tests like PancreaSeq.

More magnesium may lower risk of pancreatic cancer

The Pancreatic Cancer Action Network and the National Pancreas Foundation supported the research in part. The research appears in the journal Gut.

Source: University of Pittsburgh