Generic drugs manufactured in India are linked to significantly more “severe adverse events” for patients who use them than equivalent drugs produced in the United States, a new study finds.

These adverse events included hospitalization, disability, and in a few cases, death. Researchers found that mature generic drugs, those that had been on the market for a relatively long time, were responsible for the finding.

“Where generic drugs are manufactured can make a significant difference.”

The results show that all generic drugs are not equal, even though patients are often told that they are, says John Gray, coauthor of the study and professor of operations at The Ohio State University’s Fisher College of Business.

“Drug manufacturing regulation, and therefore quality assurance practices, differ between emerging economies like India and advanced economies like the United States,” Gray says.

“Where generic drugs are manufactured can make a significant difference.”

“The FDA assures the public that all generics patterned after the same original drug should be equivalently safe and effective, however, this is not necessarily the case when it comes to generic drugs made in India,” adds another coauthor, George Ball, associate professor of operations and decision technologies and Weimer Faculty Fellow at Indiana University’s Kelley School of Business.

The research appears in the journal Production and Operations Management.

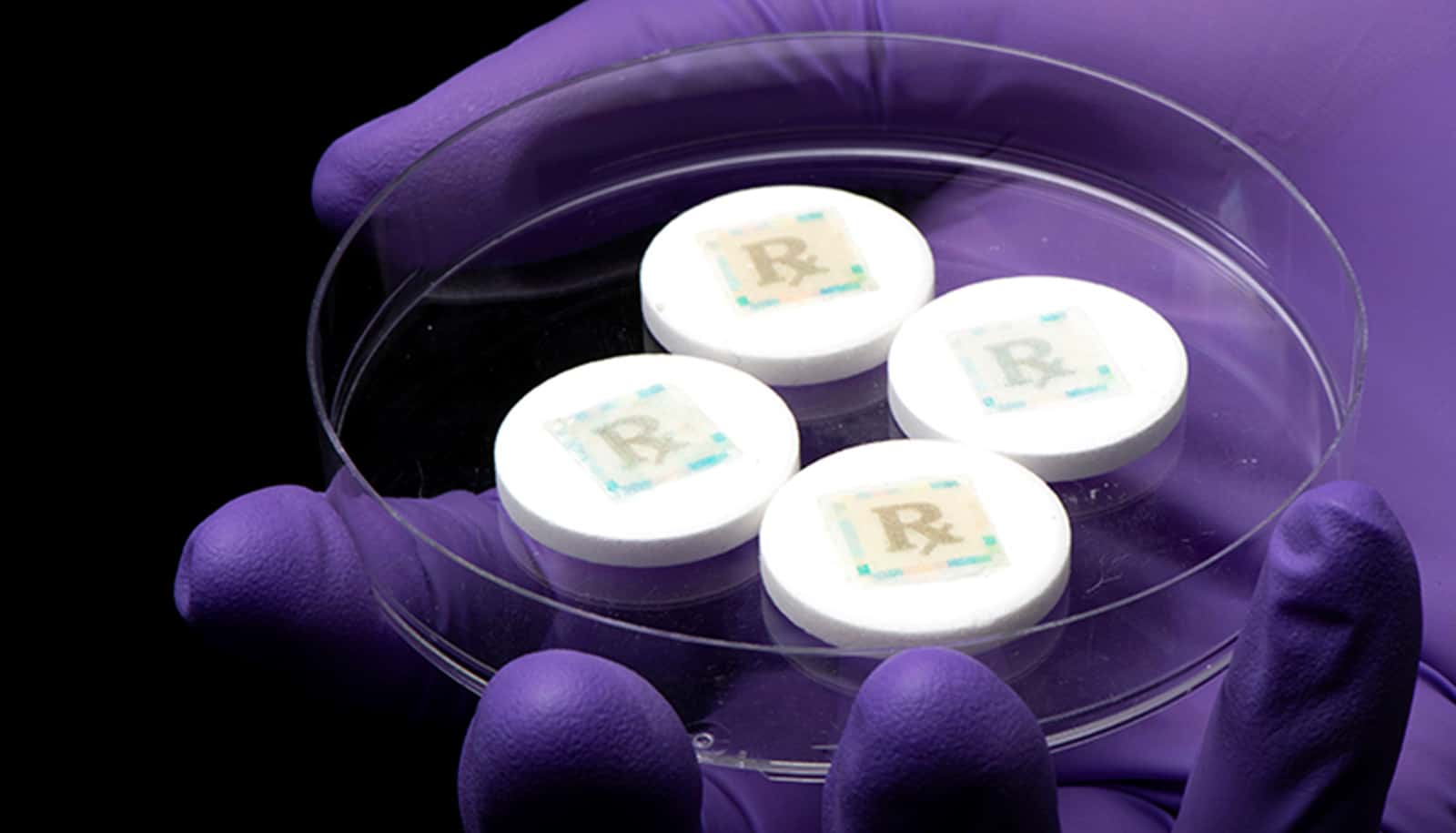

The study is significant because it is the first to be able to link a large sample of generic drugs to the actual plant where they were manufactured. The FDA will not release that information through the Freedom of Information Act process. But Gray says research leader In Joon Noh, who received his PhD at Ohio State and is now an assistant professor at Korea University, figured out how to use what is called the Structured Product Labeling dataset to link drugs to the factory where they were produced.

“Overcoming this lack of transparency of drug manufacturing location is one of the major accomplishments of our study,” Gray says.

Another key to the study is that it matched the drugs made in India to the same drugs made in the United States. The drugs had the same active ingredients, the same dosage form, and the same route of administration.

“That means the drugs are pharmaceutically equivalent and we are comparing apples to apples,” he says.

The researchers matched 2,443 drugs made in the United States and in emerging economies. Although the researchers included other countries in their analysis, 93% of generic drugs from emerging economy countries are made in India, so India data fully explained the results.

The researchers compared the frequency with which drugs were associated with adverse event reports for generic drugs made in India versus the matched drugs made in the United States. These adverse event reports are available in the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS).

Although the FAERS includes all reported adverse events, in this study the researchers only used those with the most serious outcomes, including hospitalization, disability, and death.

Results showed that the number of severe adverse events for generic drugs made in India was 54% higher than for equivalent matched generic drugs made in the United States. That was after taking into account a variety of other factors that could have affected the results, including the volume of drugs sold.

The findings were driven by drugs that had been on the market for a longer time.

“In the pharmaceutical industry, the older drugs get cheaper and cheaper and the competition gets more intense to hold down costs,” Gray says. “That may result in operations and supply chain issues that can compromise drug quality.”

Gray emphasizes that the results shouldn’t be taken as a reason to stop overseas production of generic drugs.

“There are good manufacturers in India, there are bad manufacturers in the US, and we’re not advocating for ending offshore production of drugs or bashing India in any way,” Gray says.

“We believe this is a regulatory oversight issue that can be improved.”

Gray says one key issue is that when the FDA inspects plants that make generic drugs in the United States, the inspections are unannounced. But in overseas locations, the inspections are arranged in advance, which may allow manufacturers to hide problems and make it harder for the FDA to find those that do exist. Making all inspections unannounced could make a big difference, he says.

“A key recommendation we make in this study is for the FDA to make drug manufacturing location, such as the country of manufacture, and drug quality, transparent for consumers,” Ball adds. “This can help create a market in which drug quality is incentivized more than it is today.”

Other authors include Zachary Wright, who will receive his PhD from Ohio State and is now an assistant professor at Brigham Young University; and Hyunwoo Park, a former assistant professor at Ohio State, now at Seoul National University.

Several of the authors on this paper have worked closely with the Food and Drug Administration on federal grants and contracts, though this study was conducted completely independent of the FDA. These authors say working closely with the FDA gave them a deep appreciation for the importance of studying generic drug quality.

Editor’s note: This is a joint news release with The Ohio State University.

Source: Indiana University