Gender stereotyping significantly affects the way we evaluate products, according to new research.

A new study finds that in traditionally male-oriented markets—beers, power tools, or automobile parts, for instance—goods women make can stack up pretty negatively.

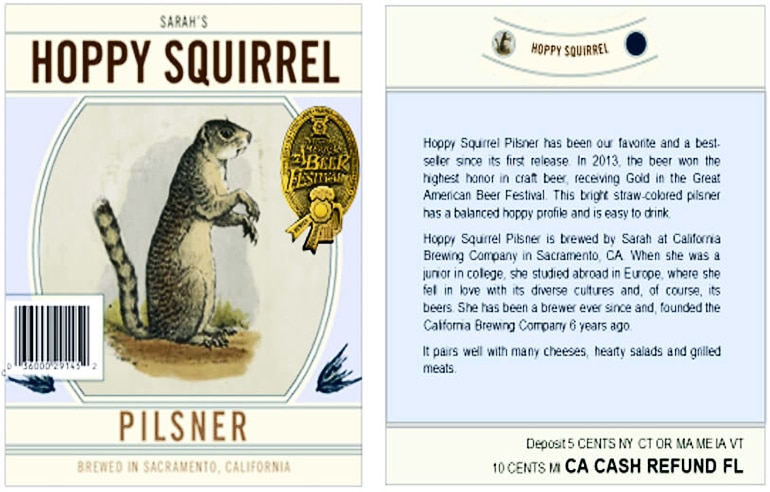

Imagine you’re reading the label of a craft beer. Among the notes you see the name of the brewer: Jane. Does knowing a woman made this beer change your perception of it? Will it taste as good as a beer a man made?

Or say you’re buying cupcakes and you see a man, John, baked them. What’s the impact on your expectations? Are John’s cupcakes likely to be as delicious as, say, Jane’s?

“Our research suggests that customers don’t value and are less inclined to buy traditionally male products if they think they’ve been manufactured by women,” says Shelley J. Correll, a researcher at Stanford Univesity. “There’s an assumption that your woman-made craft beer, screwdriver, or roof rack just won’t be as good.”

Craft beer and cupcakes

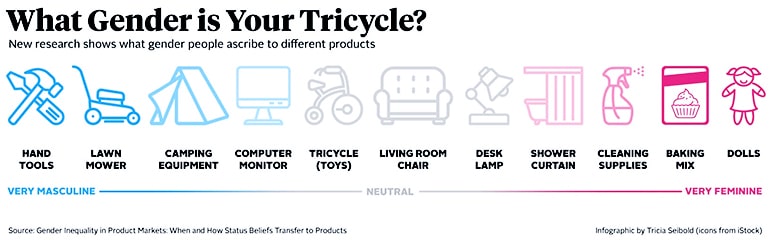

Research shows people typically evaluate women more negatively than men in the workplace, but Correll and colleague Sarah A. Soule wondered whether those gender stereotypes extended to items women make. They first surveyed 150 people—a random mix of men and women—asking them to rate consumer products in terms of how masculine or feminine they believed the items to be.

“We asked them to look at around 360 products on the Jet.com retail platform, from fairly intuitive products like golf clubs and baby clothes, to less obvious things like lamps or air conditioning units or even bottles of water,” says Correll.

“It’s funny how there tends to be consensus about the gender-typing of some products. Bacon, for instance, is almost universally seen as male, while coffee is rated more gender neutral.”

Using these insights, Correll and Soule focused in on two products: craft beer and cupcakes, seen as equally masculine and feminine, respectively.

“…across the board, identical products are cumulatively disadvantaged purely because they are woman-made.”

“After establishing that craft beer is typically viewed as masculine, we wanted to test people’s assumptions about beer that had hypothetically been brewed by either a woman or a man,” says Correll. “And the same for cupcakes, which are rated as more feminine. Would people see a cupcake made by a man as inferior to one made by a woman?”

They asked over 200 volunteers to assess a craft beer label, changing only the name of the brewer in each case, to see if gender affected their perceptions. Similarly, the researchers showed another set of participants a cupcake label, altering only the name of the baker, and surveyed them for their attitudes toward the sweet treat based on the gender of the baker.

The results were striking.

Lower grades

With craft beer, when consumers believed the producer was a woman, they claimed they would pay less for the beer, and they had lower expectations of taste and quality.

But for the cupcake, there was little noticeable difference in attitudes toward producers who were women versus men.

“What we’re seeing here is that woman-made goods for sale in male-typed markets are being penalized for no reason other than the fact they are made by women,” Soule says.

“Imagine that these goods are being graded on a scale of A to F. What you find is that an equivalent product, when made by a woman rather than a man, is knocked down to an A- or a B+ while a man’s product consistently gets an A. The same isn’t true for man-made products that target women. So the result is that across the board, identical products are cumulatively disadvantaged purely because they are woman-made.”

And this effect might apply to more than consumer goods, warns Correll.

“When we told participants that a woman-brewed beer had won an award, they rated is just as highly as if it was brewed by a man…”

“We’ve looked at craft beer and cupcakes, but this could extend to any type of product from academic research to entrepreneurship,” she says. “And that has very serious implications for all of us.”

There are, however, some encouraging discoveries within the research findings.

Industry awards and the degree of consumer knowledge or expertise about a product appear to attenuate and even eliminate the gender bias altogether.

“When we told participants that a woman-brewed beer had won an award, they rated is just as highly as if it was brewed by a man,” says Correll. “It seems that awards vouch for the competence of the woman.”

The gender of the brewer also doesn’t affect beer snobs, notes Soule.

“We find that individuals who have some degree of expertise or who really know about a product tend to focus on its features and don’t care whether it’s manufactured by men or women,” she says.

How to change things

So what’s the answer for women looking to thrive in male-oriented markets? Should they focus on awards, target connoisseurs, or simply conceal their gender?

The long-term solution, say Correll and Soule, doesn’t lie in women modifying their behavior. The answer is in changing people’s stereotypical thinking at a societal level and building awareness of inherent biases that we all bring to our purchasing and other behaviors—an enormous challenge, they both acknowledge.

Meanwhile, organizations and industry associations would do well to be mindful of the importance of gender bias and build specific expertise in things like employee evaluation and hiring processes.

“As our research finds, the more expert you are about a product, the less gender bias affects your thinking. For businesses, there’s a key imperative here to build leaders’ expertise in things like employee review and appraisal to minimize gender stereotyping,” says Correll.

Industry organizations too should be cognizant of the fact that awards can eliminate bias, notes Soule. She suggests that awarding committees consider making sure that they give prestigious awards proportionately to eligible men and women.

“We’re not recommending awards ‘quotas’ per se, but these organizations need to understand the important and helpful role they can play in changing perceptions and driving us forward toward a society where the odds are not quite so stacked against women.”

Source: Stanford University