Scientists have discovered a lone mutation in a single gene that causes an inherited form of frontotemporal dementia makes it harder for neurons in the brain to communicate with one another, leading to neurodegeneration.

Unlike the more common Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia tends to afflict young people. People with the illness typically begin to suffer memory loss by their early 60s, but it can affect some people as young as their 40s. There are no effective treatments for the condition, which accounts for an estimated 20 percent of all cases of early-onset dementia.

The new findings zero in on the MAPT gene, which makes a protein called tau, also associated with cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Identifying the downstream effects of the mutation could help identify new treatment targets for frontotemporal dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and other tau-related illnesses, including Parkinson’s disease.

“We have demonstrated that we can capture changes in human cells cultured in a dish that also are appearing in the brains of individuals… with frontotemporal dementia,” says Celeste M. Karch, assistant professor of psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis and a senior author of the paper, which appears in Translational Psychiatry.

“Importantly, the approach we are using allows us to zero in on genes and pathways that are altered in cells and in patient brains that may be influenced by compounds already approved by the FDA. We want to evaluate whether any of these compounds could prevent memory loss, or even restore memory, in people with frontotemporal dementia by improving the function of these pathways that have been disrupted,” Karch says.

Communication breakdown

For the study, researchers gathered skin samples from patients with frontotemporal dementia with a specific mutation in the MAPT gene.

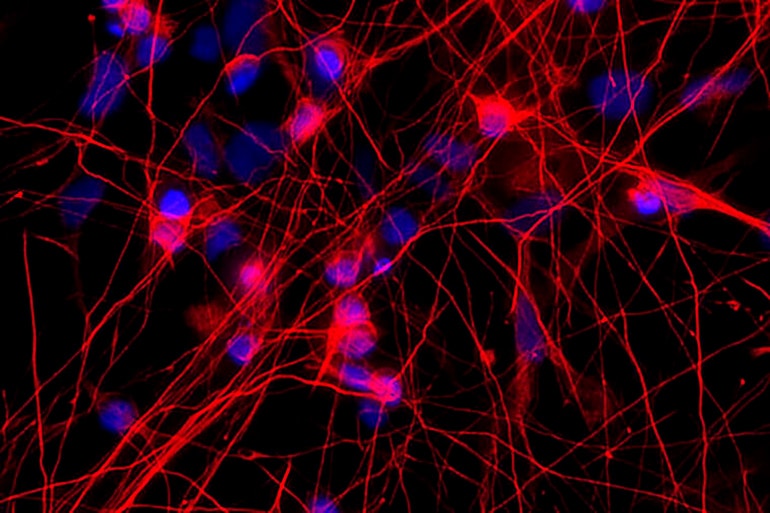

The researchers then converted the patients’ skin cells into induced pluripotent stem cells, which have the ability to grow and develop into any cell type in the body. The researchers treated these stem cells with compounds that coaxed them to grow and develop into neurons, which also had the MAPT mutation. Then, using gene-editing technology called CRISPR, the researchers eliminated the mutation in some neurons but not others and observed what happened.

“We found differences in genes and pathways related to cellular communication, suggesting the mutation alters neurons’ ability to communicate,” says co-senior author Carlos Cruchaga, associate professor of psychiatry.

“The initial mutation in MAPT is the key change that starts the disease, and it is a potential target for therapy, but there are other genes downstream from the MAPT gene that also are good targets that may be used to treat the disease.”

Damage prevention

In neurons with the mutation, the researchers found alterations in 61 genes, including genes that make GABA receptors on brain neurons. GABA receptors are the major inhibitory receptors in the brain, and they are key to several types of communication between brain cells.

The researchers identified similar disruptions in genes that make GABA receptors when they did experiments in animal models and analyzed brain tissue from patients who had died with frontotemporal dementia. They also looked at findings from a genomewide association study of more than 2,000 patients with frontotemporal dementia and more than 4,000 without the disorder. That analysis also pointed to GABA-related genes as potential targets.

“Using our stem cell-derived neurons, we have the opportunity, in human tissue, to target some of those GABA genes in advance of the neurodegeneration we see in the postmortem tissue we study,” Harari says. “So, at least in cell cultures, we can learn whether potential therapies prevent the damage caused by inherited forms of frontotemporal dementia.”

By studying rare, inherited forms of brain diseases, the researchers believe they will learn a great deal about how to treat the more common forms of those disorders.

“Genetic forms of frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease are caused by rare mutations,” Cruchaga says. “But they have much in common with the more typical cases of those diseases. If we understand these cases caused by inherited mutations, we also should better understand the common forms of these diseases.”

The National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health and the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s Network funded the study. The Tau Consortium, the Alzheimer Association, the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases, Raul Carrea Institute for Neurological Research, the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, AMED, and the Korea Health Technology R&D project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute provided additional funding.