A newly rediscovered piece of sheet music honoring Frederick Douglass sheds light on his place in the abolitionist movement and the history of other notable figures in the movement.

In 1847, Frederick Douglass was getting ready to leave England where had lived to avoid being recaptured after his earlier escape from slavery in Maryland. He had crisscrossed Britain for the last 19 months while lecturing on the evils of slavery in his native country. Now that supporters had raised 150 English pounds (about $750 then) to buy his legal freedom, he was able to return to his family in the United States. Yet, his safe passage was by no means guaranteed.

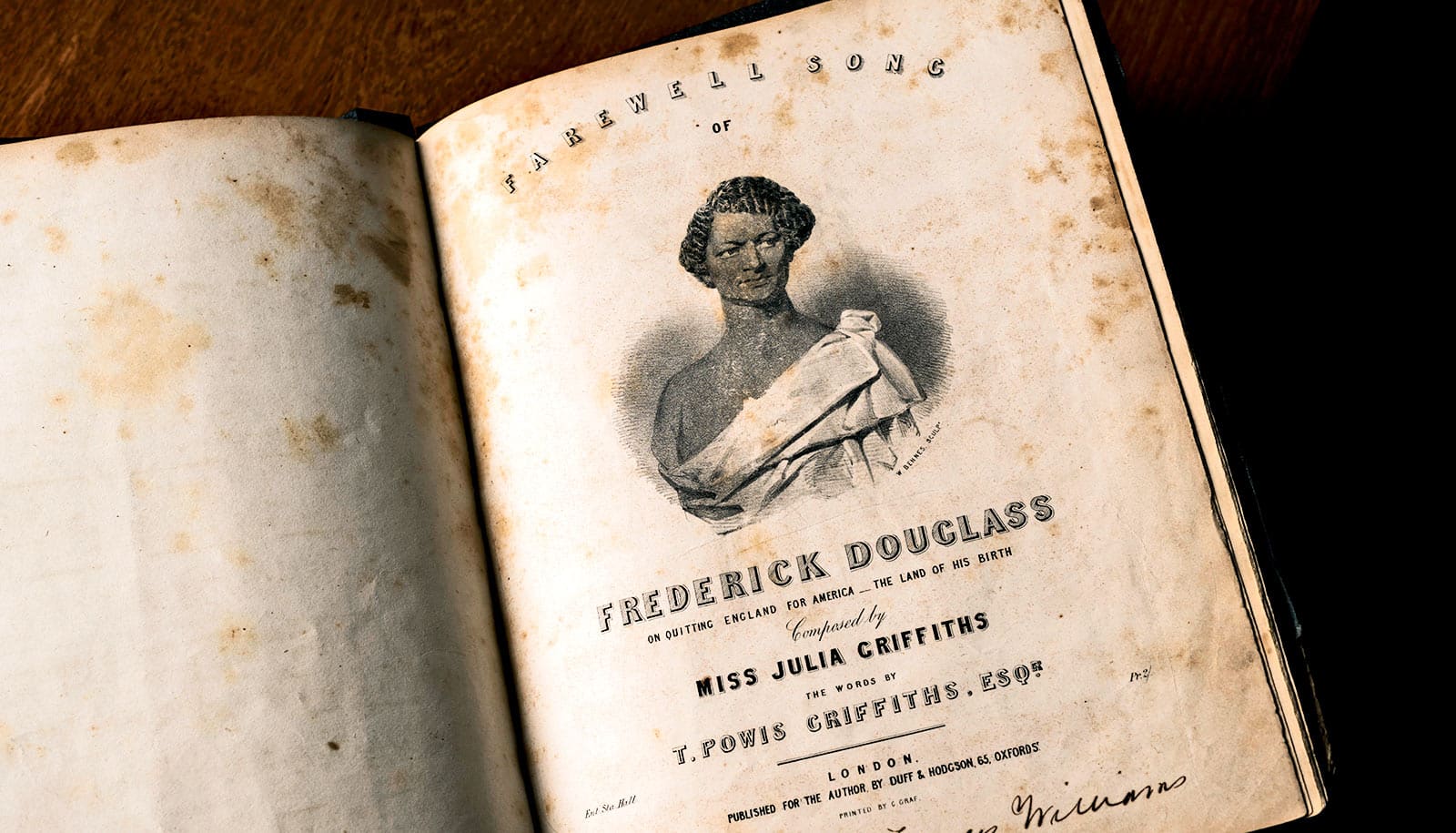

To commemorate the historic event, Douglass’s close companion and fellow abolitionist, Julia Griffiths, an Englishwoman, wrote the “Farewell Song of Frederick Douglass.” She scored the music for voice and piano while her brother, a lawyer named T. Powis Griffiths, penned the lyrics.

Singing history

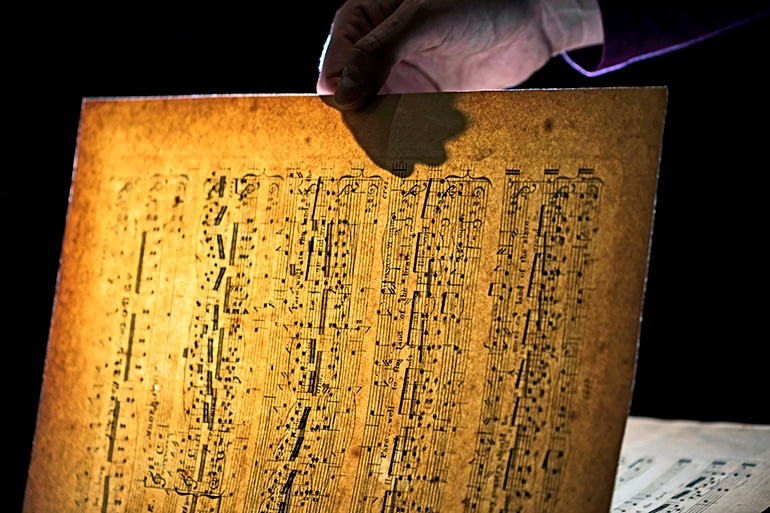

Earlier this year, the University of Rochester libraries’ rare books, special collections, and preservation department acquired a well-worn, black cloth book of bound sheet music. Now referred to as the Francis A. Williams songbook, it bears the name of its former owner stamped in gold lettering on its cover. Tucked inside, among a total of sixteen pieces of music, is the farewell song written expressly for the famous abolitionist and social reformer, who would have turned 200 this year.

Having one’s own sheet music bound was not uncommon in the 19th century, says Autumn Haag, the special collections librarian and archivist for research and collections at the University of Rochester. What makes this book so valuable is that only two known copies of the Douglass song have survived—one at the British Library in London and now one at the University of Rochester.

Subtitled “On Quitting England for America—the Land of His Birth,” the words decry America as a brutish country. The song styles England as the “land of the free, the land of the brave” while the lyrics lament “Alas! that my country should be America! land of the slave.”

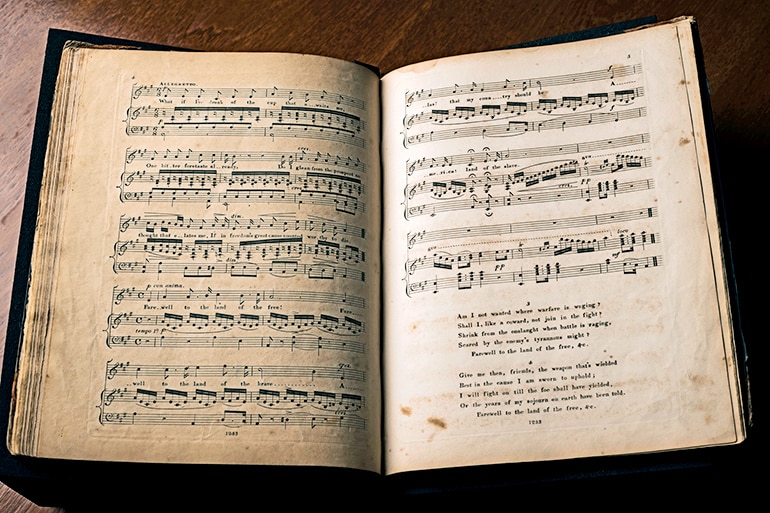

Written from Douglass’s perspective, the four stanzas arrive at the conclusion that the abolitionist leader needs to return to America and join the fight against slavery, even if it could spell his own death.

“Shall I, like a coward, not join the fight? Shrink from the onslaught when battle is raging/Scared by the enemy’s tyrannous might? […] I will fight on till the foe shall have yielded/Or the years of my sojourn on earth have been told,” wrote lawyer Griffiths in Douglass’s imaginary voice.

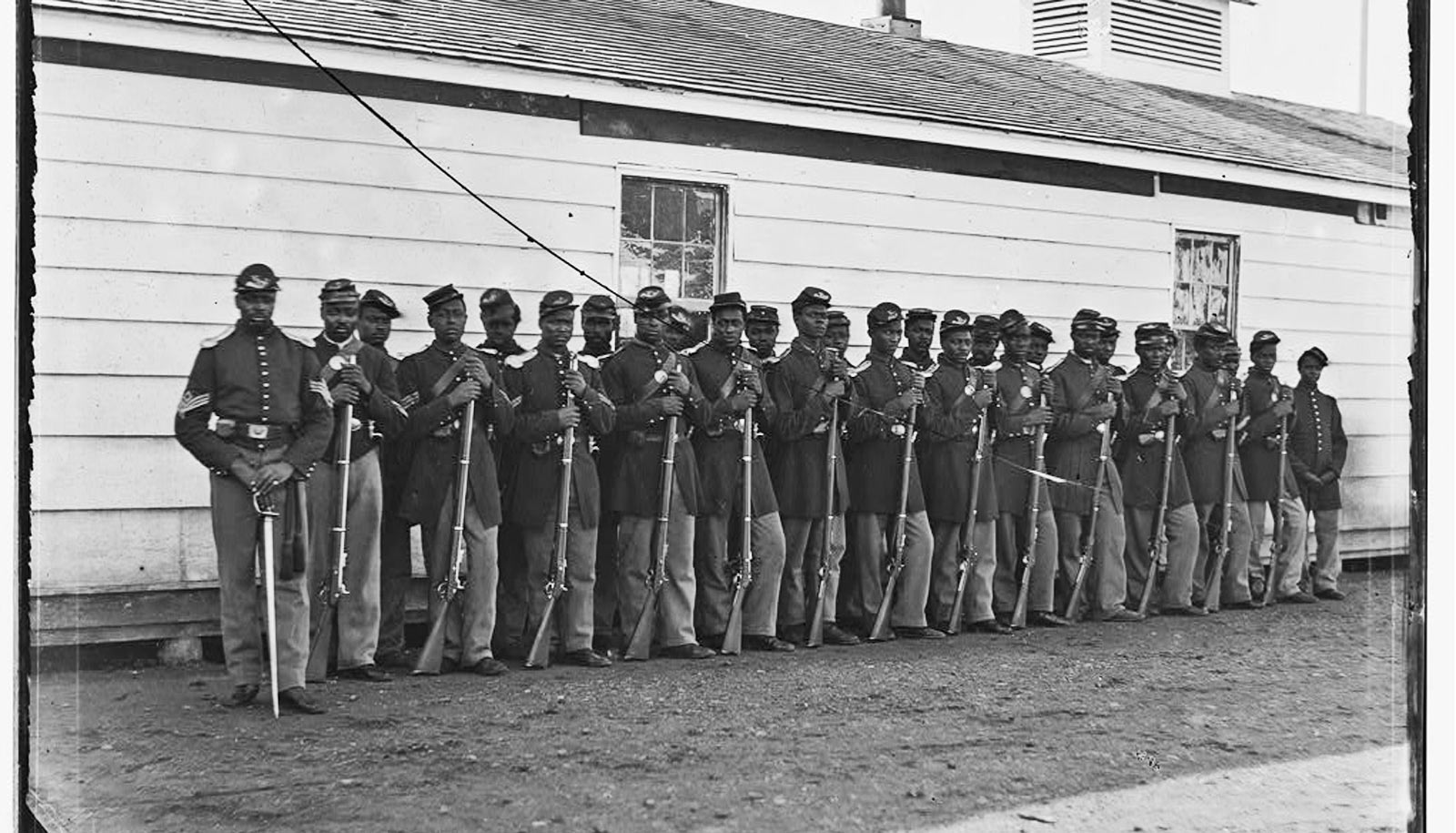

Haag says she is struck by the use of martial imagery and words like “warfare,” “battle,” and “weapon”, especially in the last two verses. “It feels like the lyrics are already foreshadowing the Civil War,” which was to break out barely 14 years later.

The book’s title page shows a stylized image of Douglass, wearing a classical-style toga artfully draped over his left shoulder, meant as an allusion to ancient Greece or Rome. The image, depicting Douglass with a stoic look, sharp jawline, and a bit of a Roman nose is not a true representation of the real Douglass, says Haag.

Was it propaganda? she muses. “Propaganda has sometimes negative connotations, but yes. It was written for a purpose.” It was written to remind Douglass’s supporters in England what he was returning home to, and to highlight to abolitionists in the United States the essential difference between the two countries at the time, says Haag.

Transatlantic journey

How did the rare sheet music end up in America?

Haag has worked to piece together how the book ended up in America. In the back of the bound volume, she found a newspaper clipping of music, cut out from a Cincinnati newspaper—enough for Haag to start a genealogical search for its previous owner, a Francis A. Williams in Ohio.

Soon she discovered that Williams was biracial, and one of the first women to graduate from Oberlin College, where she had studied music. She married a Peter H. Clark, one of Ohio’s most effective black abolitionist writers and speakers.

At this point, the songbook’s provenance and the song’s subject begin to intertwine: in 1853 Douglass appointed Clark secretary of the National Convention of Colored Men. Three years later, the Clarks moved to Rochester and took up residence in the Douglass home with their infant daughter while Clark worked as an assistant on the Frederick Douglass’ Paper (formerly the North Star). Barely a year later, the young family moved back to Cincinnati where Clark found other employment.

“It’s very possible that Francis brought the book along with her to Rochester,” says Haag. “While we don’t know if she performed the song at the Douglass home, we know that Frederick Douglass played the violin and loved music.”

Of course, there’s also a chance that the song’s English author, who seven years earlier had also lived in the Douglass home, had brought another copy. Either way, Haag says, “we feel pretty certain that the music was in Rochester before and we’re bringing it now full circle.”

In early December, the song will be performed live at the Hochstein Performance Hall in Rochester, which incidentally is the same venue where Douglass’s funeral took place in 1895.

“With just two surviving copies, the music probably hasn’t been played in the last 100 years,” says Haag.

The song’s lyrics

Farewell Song of Frederick Douglass

On Quitting England for America—the Land of his Birth

Farewell to the land of the free! Farewell to the land of the brave. Alas! That my country should be America! Land of the slave.

1 What if the Negroes despis’d and degraded

And scorn and reproach are heap’d on his head

Perish the thought that would leave him unaided

American soil shall be that which I tread.

Farewell to the land of the free! Farewell to the land of the brave. Alas! That my country should be America! Land of the slave. [repeat]

2 What if I’ve drunk of the cup that awaits me,

One bitter foretaste already,

Do I glean from the prospect no thought that elates me,

If in freedom’s great cause counted worthy to die.

Farewell to the land of the free! Farewell to the land of the brave. Alas! That my country should be America! Land of the slave. [repeat]

3 Am I not wanted where warfare is waging?

Shall I, like a coward, not join the fight?

Shrink from the onslaught when battle is raging,

Scared by the enemy’s tyrannous might?

Farewell to the land of the free! Farewell to the land of the brave. Alas! That my country should be America! Land of the slave. [repeat]

4 Give me then, friends, the weapon that’s wielded

Best in the cause I am sworn to uphold;

I will fight on till the foe shall have yielded,

Or the years of my sojourn on earth have been told.

Farewell to the land of the free, etc.

Source: University of Rochester