The amount of water that hydraulic fracturing uses per well surged by up to 770 percent between 2011 and 2016 in all major US shale gas and oil production regions, according to a new study.

If this rapid intensification continues, fracking’s water footprint could grow by up to 50-fold in some regions by the year 2030.

The volume of brine-laden wastewater that fracked oil and gas wells generated during their first year of production also increased by up to 1,440 percent during the same period, the study shows.

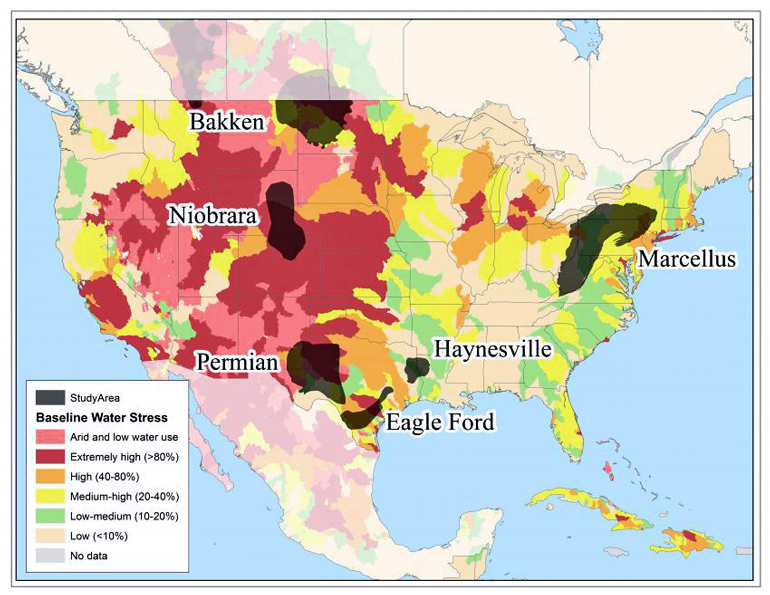

If this rapid intensification continues, fracking’s water footprint could grow by up to 50-fold in some regions by the year 2030—raising concerns about its sustainability, particularly in arid or semi-arid regions in western states, or other areas where groundwater supplies are stressed or limited.

“Previous studies suggested hydraulic fracturing does not use significantly more water than other energy sources, but those findings were based only on aggregated data from the early years of fracking,” says Avner Vengosh, professor of geochemistry and water quality at the Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University.

“After more than a decade of fracking operation, we now have more years of data to draw upon from multiple verifiable sources. We clearly see a steady annual increase in hydraulic fracturing’s water footprint, with 2014 and 2015 marking a turning point where water use and the generation of flowback and produced water began to increase at significantly higher rates,” Vengosh says.

“While the extraction of shale gas and tight oil has become more efficient over time as the net production of natural gas and oil from these unconventional wells has increased, the amount of water used for hydraulic fracturing and the volume of wastewater produced from each well have increased at much higher rates, making fracking’s water footprint much higher,” he adds.

To conduct the study, the researchers collected and analyzed six years of data on water use and natural gas, oil, and wastewater production from industry, government, and non-profit sources for more than 12,000 individual wells located in all major US shale gas and tight oil producing regions. Then they used these historical data to model future water use and first-year wastewater volumes under two different scenarios.

The models showed that if current low oil and gas prices rise and production again reaches levels seen during fracking’s heyday in the early 2010s, cumulative water use and wastewater volumes could surge by up to 50-fold in unconventional gas-producing regions by 2030, and by up to 20-fold in unconventional oil-producing regions.

“Even if prices and drilling rates remain at current levels, our models still predict a large increase by 2030 in both water use and wastewater production,” says Andrew J. Kondash, a PhD student in Vengosh’s lab who was lead author of the paper.

Fracking chemicals may harm developing immune system

Brines extracted with the gas and oil from deep underground blended with some of the water initially injected into the well during hydraulic fracturing, chiefly comprise a well’s wastewater. These brines are typically salty and may contain toxic and naturally occurring radioactive elements, making them difficult to treat and dispose of safely.

To keep up with the growing volume of wastewater that fracking is now generating, drilling companies increasingly are injecting it back deep underground into wastewater wells. This practice helps keep the wastewater out of local water supplies but has been linked to small- to medium-sized earthquakes in some locations.

“New drilling technologies and production strategies have spurred exponential growth in unconventional oil and gas production in the United States and, increasingly, in other parts of the world,” Kondash says.

“This study provides the most accurate baseline yet for assessing the long-term environmental impacts this growth may have, particularly on local water availability and wastewater management,” he says.

Fracking exposure leads to more fat cells

“Lessons learned from production development in the United States can directly inform the planning and implementation of hydraulic fracturing practices elsewhere as other countries such as China, Mexico, and Argentina bring their unconventional natural gas reserves online,” he says.

The findings appear in Science Advances. Funding for the research came from the National Science Foundation.

Source: Duke University