Children who live fracking sites at birth were two to three times more likely to be diagnosed with leukemia between the ages of 2 and 7 than those who did not, according to a new study.

The study, which appears in Environmental Health Perspectives, took into account other factors that could influence cancer risk.

The registry-based study included nearly 2,500 Pennsylvania children, 405 of whom were diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the most common type of cancer in children.

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, also referred to as ALL, is a type of leukemia that arises from mutations to lymphoid immune cells. Although long-term survival rates are high, children who survive this disease may be at higher risk of other health problems, developmental challenges, and psychological issues.

Unconventional oil and gas (UOG) development, more commonly referred to as fracking (short for hydraulic fracturing), is a method for extracting gas and oil from shale rock. The process involves injecting water, sand, and chemicals into bedrock at high pressure, which allows gas and oil to flow into a well and then be collected for market.

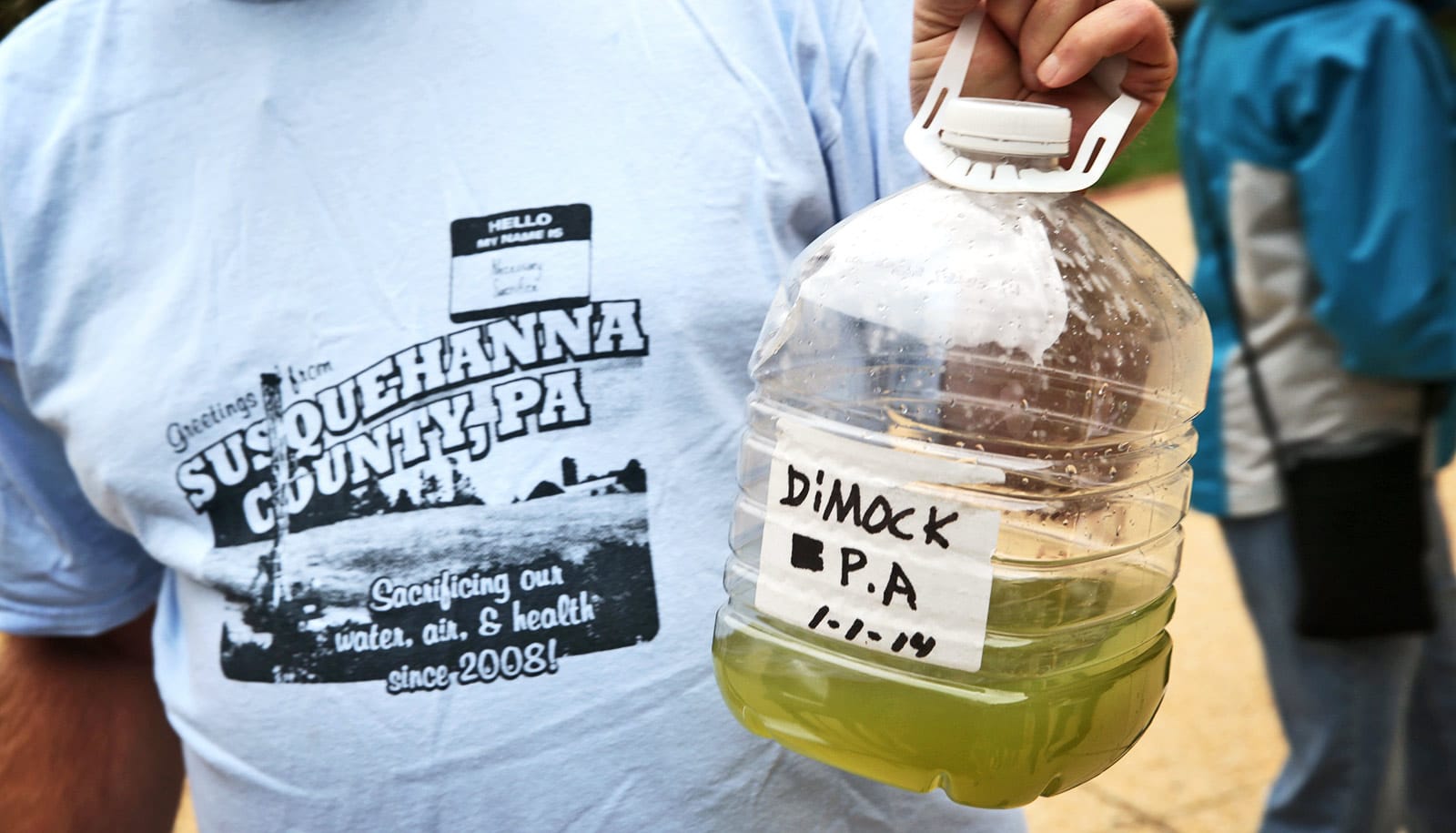

For communities living nearby, UOG development can pose a number of potential threats. Chemical threats include, for example, air pollution from vehicle emissions and well and road construction, and water pollution from hydraulic fracturing or spills of wastewater.

Hundreds of chemicals have been reportedly used in UOG injection water or detected in wastewater, some of which are known or suspected to be cancer causing. The paucity of data on the association between UOG and childhood cancer outcomes has fueled public concerns about possible cancer clusters in heavily drilled regions and calls for more research and government action.

“Unconventional oil and gas development can both use and release chemicals that have been linked to cancer, so the potential for children living near UOG to be exposed to these chemical carcinogens is a major public health concern,” says senior author Nicole Deziel, associate professor of epidemiology at the Yale School of Public Health.

“Studies of UOG exposure and cancer are extremely few in number. We set out to conduct a high-quality study to further investigate this potential relationship,” says first author Cassandra Clark, a postdoctoral associate at the Yale Cancer Center. “Our results indicate that exposure to UOG may be an important risk factor for ALL, particularly for children exposed in utero.”

The study also found that drinking water could be an important pathway of exposure to oil and gas-related chemicals. The authors applied a new exposure metric in this study that they call “IDups” (which stands for “inverse distance to the nearest upgradient unconventional oil and gas well”).

This means that the researchers identified UOG wells that fell within a child’s watershed area—the zone from which a drinking water well serving their home would likely draw water—and calculated the distance from the home to the nearest of those UOG wells. UOG wells falling within the watershed area are expected to be more likely to affect the home’s drinking water supply, they say.

“Previous health studies have found links between proximity to oil and gas drilling and various children’s health outcomes,” says Deziel. “This study is among the few to focus on drinking water specifically and the first to apply a novel metric designed to capture potential exposure through this pathway.”

This work adds to a growing body of literature on UOG exposure and children’s health used to inform policy, such as setback distances (the required minimum distance between a private residence or other sensitive location and a UOG well).

Current setback distances are the subject of much debate in the US, with some calling for setback distances to be lengthened to more than 305 meters (1,000 feet) and as far as 1,000 meters (3,281 feet). The allowable setback in Pennsylvania, where the study was conducted, is 500 feet, or 152 meters.

“Our findings of increased risk of ALL at distances of two kilometers or more from UOG operations, in conjunction with evidence from numerous other studies, suggest that existing setback distances, which may be as little as 150 feet, are insufficiently protective of children’s health,” Clark says. “We hope that studies like ours are taken into account in the ongoing policy discussion around UOG setback distances.”

Source: Yale University