A new study provides a glimpse into dinosaur and bird diversity in Patagonia during the Late Cretaceous, just before the non-avian dinosaurs went extinct.

Fossils researchers have discovered represent the first record of theropods—a dinosaur group that includes both modern birds and their closest non-avian dinosaur relatives—from the Chilean portion of Patagonia.

The finds include giant megaraptors with large sickle-like claws and birds from the group that also includes today’s modern species.

“The fauna of Patagonia leading up to the mass extinction was really diverse,” says lead author Sarah Davis, who completed the work as part of her doctoral studies with Julia Clarke, professor at the University of Texas at Austin Jackson School of Geosciences geological sciences department. “You’ve got your large theropod carnivores and smaller carnivores as well as these bird groups coexisting alongside other reptiles and small mammals.”

The study appears in the Journal of South American Earth Sciences.

Since 2017, members of the Clarke lab, including graduate and undergraduate students, have joined scientific collaborators from Chile in Patagonia to collect fossils and build a record of ancient life from the region. Over the years, researchers have found abundant plant and animal fossils from before the asteroid strike that killed off the dinosaurs.

The new study focuses specifically on theropods, with the fossils dating from 66 to 75 million years ago.

Non-avian theropod dinosaurs were mostly carnivorous, and include the top predators in the food chain. This study shows that in prehistoric Patagonia, these predators included dinosaurs from two groups—megaraptors and unenlagiines.

Reaching over 25 feet long, megaraptors were among the larger theropod dinosaurs in South America during the Late Cretaceous. The unenlagiines—a group with members that ranged from chicken-sized to over 10 feet tall—were probably covered with feathers, just like their close relative the velociraptor. The unenlagiinae fossils described in the study are the southernmost known instance of this dinosaur group.

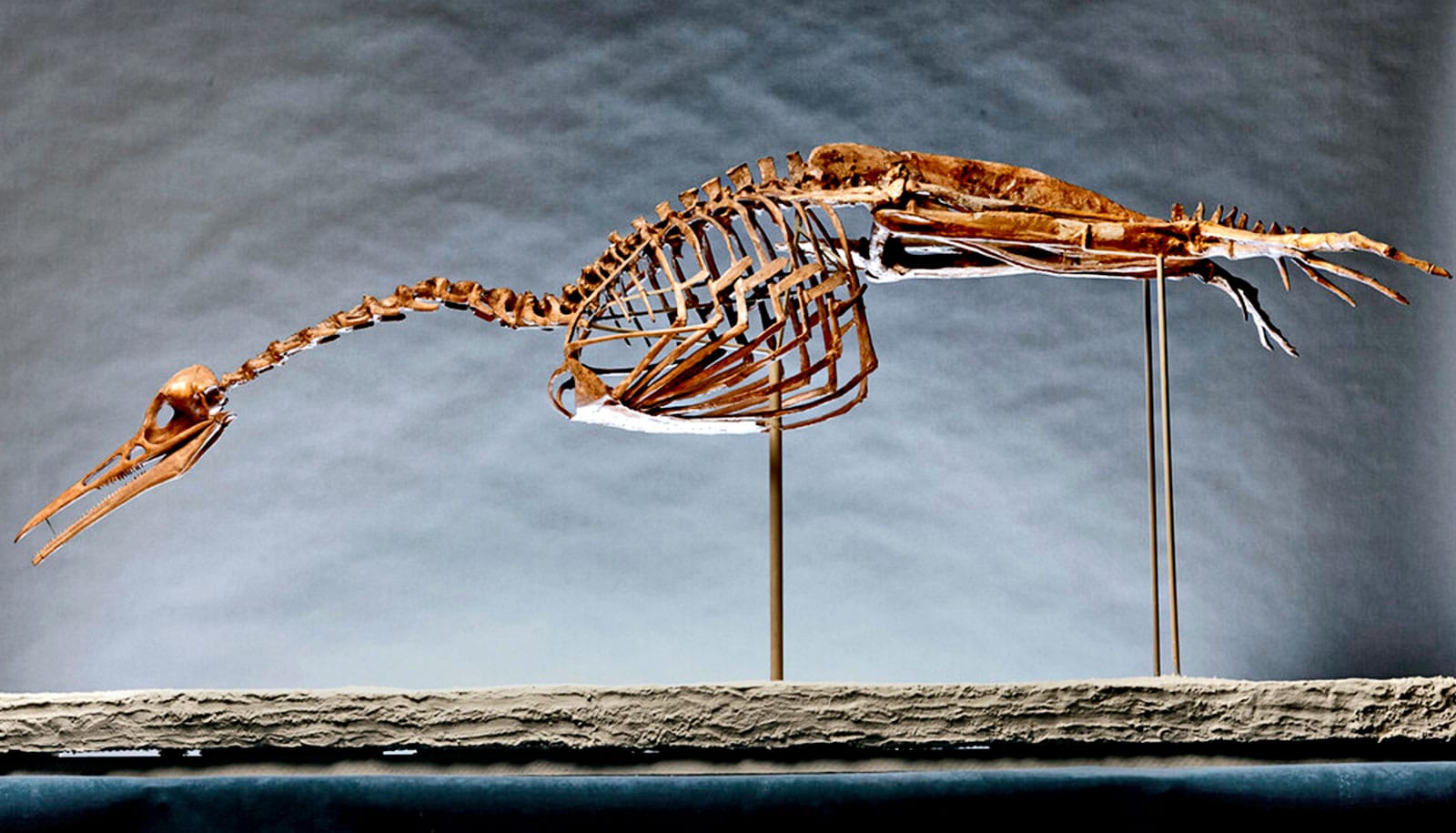

The bird fossils were also from two groups—enantiornithines and ornithurines. Although now extinct, enantiornithines were the most diverse and abundant birds millions of years ago. These resembled sparrows—but with beaks lined with teeth. The group ornithurae includes all modern birds living today. The ones living in ancient Patagonia may have resembled a goose or duck, though the fossils are too fragmentary to tell for sure.

The researchers identified the theropods from small fossil fragments; the dinosaurs mostly from teeth and toes, the birds from small bone pieces. The enamel glinting on the dinosaur teeth helped with spotting them among the rocky terrain, Davis says.

Some researchers have suggested that the Southern Hemisphere faced less extreme or more gradual climatic changes than the Northern Hemisphere after the asteroid strike. This may have made Patagonia, and other places in the Southern Hemisphere, a refuge for birds and mammals and other life that survived the extinction.

Davis says that this study can aid in investigating this theory by building up a record of ancient life before and after the extinction event.

These past records are key to understanding life as it exists today, says coauthor Marcelo Leppe, the director of the Antarctic Institute of Chile.

“We still need to know how life made its way in that apocalyptic scenario and gave rise to our southern environments in South America, New Zealand, and Australia,” he says. “Here theropods are still present—no longer as dinosaurs as imposing as megaraptorids—but as the diverse array of birds found in the forests, swamps and marshes of Patagonia, and in Antarctica and Australia.”

Additional coauthors are from the University of Chile, Major University, the University of Concepción, and the Chilean National Museum of Natural History.

Source: UT Austin