Low oxygen environments set the stage for the creation of exceptional fossils, but it takes a breath of fresh air to catalyze the process, research finds.

Some of the world’s most exquisite fossil beds formed millions of years ago during time periods when the Earth’s oceans were largely without oxygen. That association has led paleontologists to believe that the world’s best-preserved fossil collections come from choked oceans.

“The traditional thinking about these exceptionally preserved fossil sites is wrong,” says lead author Drew Muscente, an assistant professor at Cornell College in Mount Vernon, Iowa who conducted the research as a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Texas at Austin’s Jackson School of Geosciences.

“It is not the absence of oxygen that allows them to be preserved and fossilized. It is the presence of oxygen under the right circumstances.”

The best-preserved fossil deposits are called “Konservat-lagerstätten.” They are rare and scientifically valuable because they preserve soft tissues along with hard ones—which in turn, preserves a greater variety of life from ancient ecosystems.

“When you look at lagerstätten, what’s so interesting about them is everybody is there,” says coauthor Brooke Bogan, an undergraduate student at the Jackson School. “You get a more complete picture of the animal and the environment, and those living in it.”

Creatures locked in shale

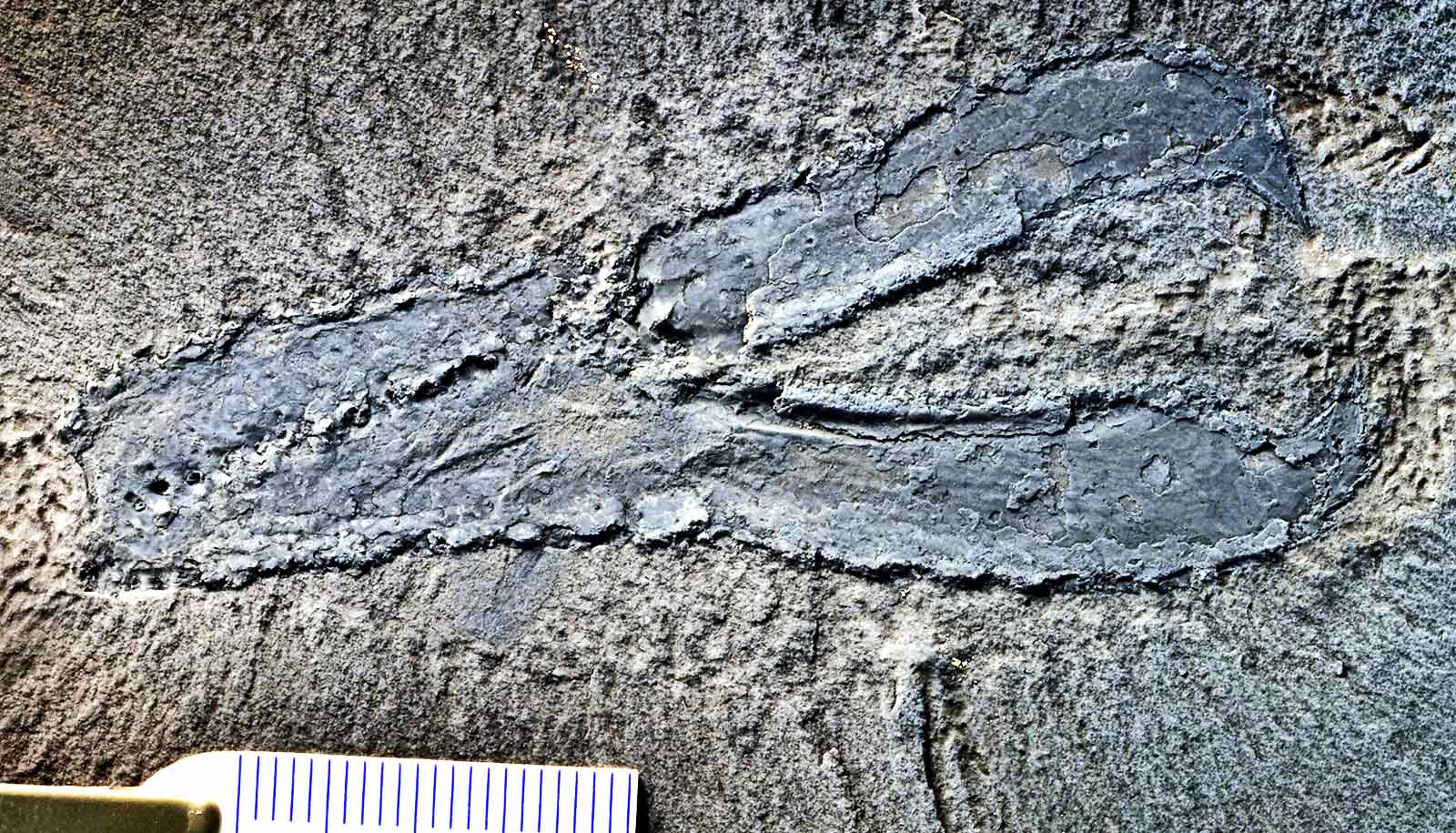

The research examined the fossilization history of an exceptional fossil site located at Ya Ha Tinda Ranch in Canada’s Banff National Park. The site, which coauthor Rowan Martindale, an assistant professor at the Jackson School, described in a 2017 paper, is known for its cache of delicate marine specimens from the Early Jurassic—such as lobsters and vampire squids with their ink sacks still intact—preserved in slabs of black shale.

During the time of fossilization, about 183 million years ago, high global temperatures sapped oxygen from the oceans. To determine if the fossils did indeed form in an oxygen-deprived environment, the team analyzed minerals in the fossils. Since different minerals form under different chemical conditions, the research could determine if oxygen was present or not.

“The cool thing about this work is that we can now understand the modes of formation of these different minerals as this organism fossilizes,” Martindale says. “A particular pathway can tell you about the oxygen conditions.”

Oxygen ups and downs

The analysis involved using a scanning electron microscope to detect the mineral makeup.

“You pick points of interest that you think might tell you something about the composition,” says coauthor Abby Creighton, an undergraduate student at the Jackson School, who analyzed a number of specimens. “From there you can correlate to the specific minerals.”

The workup revealed that the vast majority of the fossils are made of apatite—a phosphate-based mineral that needs oxygen to form. However, the researchers also found that the climatic conditions of a low-oxygen environment helped set the stage for fossilization once oxygen became available.

That’s because periods of low ocean oxygen are linked to high global temperatures that raise sea levels and erode rock, which is a rich source of phosphate to help form fossils. If the low oxygen environment persisted, this sediment would simply release its phosphate into the ocean. But with oxygen around, the phosphate stays in the sediment where it could start the fossilization process.

Muscente says that the apatite fossils of Ya Ha Tinda point to this mechanism.

The researchers plan to continue their work by analyzing specimens from exceptional fossil sites in Germany and the United Kingdom that were preserved around the same time as the Ya Ha Tinda specimens and compare their fossilization histories.

The research appears in the journal PALAIOS. James Schiffbauer of the University of Missouri is also a coauthor of the paper.

Funding for the research came from the National Science Foundation and the Jackson School of Geosciences.

Source: UT Austin