A large hole at the base of the skull offers clues to the evolution of bipedalism—walking on two feet—in humans.

Compared with those of other primates, the foramen magnum—where the spinal cord passes through—is shifted forward.

While many scientists generally attribute this shift to the evolution of bipedalism and the need to balance the head directly atop the spine, others have been critical of the proposed link.

A new study validates the connection and provides another tool for researchers to determine whether a fossil hominid walked upright on two feet like humans or on four limbs like modern great apes.

Controversy has centered on the association between a forward-shifted foramen magnum and bipedalism since 1925, when Raymond Dart discussed it in his description of “Taung child,” a 2.8-million-year-old fossil skull of the extinct South African species Australopithecus africanus. Last year, Aidan Ruth and colleagues continued to stir up the controversy when they published a paper offering additional criticisms of the idea.

Gabrielle Russo, an assistant professor at Stony Brook University, and Chris Kirk, an anthropologist at the University of Texas at Austin, now build on their own prior research to show that a forward-shifted foramen magnum exists not just in humans and their bipedal fossil relatives, but also among bipedal mammals more generally.

“This question of how bipedalism influences skull anatomy keeps coming up partly because it’s difficult to test the various hypotheses if you only focus on primates,” says Kirk. “However, when you look at the full range of diversity across mammals, the evidence is compelling that bipedalism and a forward-shifted foramen magnum go hand-in-hand.”

These pre-humans didn’t have ‘nutcracker’ jaws

In the Journal of Human Evolution, Kirk and Russo expand on research published in the same journal in 2013 by using new methods to quantify aspects of foramen magnum anatomy and sampling the largest number of mammal species to date.

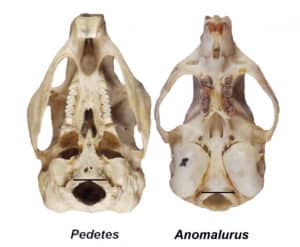

They compared the position and orientation of the foramen magnum in 77 mammal species including marsupials, rodents, and primates. Their findings indicate that bipedal mammals such as humans, kangaroos, springhares, and jerboas have a more forward-positioned foramen magnum than their quadrupedal close relatives.

“We’ve now shown that the foramen magnum is forward-shifted across multiple bipedal mammalian clades using multiple metrics from the skull, which I think is convincing evidence that we’re capturing a real phenomenon,” Russo says.

Further, the study identifies specific measurements that can be applied to future research to map out the evolution of bipedalism. “Other researchers should feel confident in making use of our data to interpret the human fossil record.”

Source: University of Texas at Austin