Food insecurity is estimated to affect up to 24% of US military veterans and risks are significantly higher for people of color and women, according to a new study.

Food insecurity is defined as a limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate food.

The research also shows that veterans with medical and trauma-related conditions, as well as unmet social needs like housing instability, are more likely to experience food insecurity.

“If we don’t specifically ask veterans about their food needs, we are going to be missing people who are experiencing hardship.”

Researchers analyzed data with a focus on revealing the characteristics of veterans at the highest risk of food insecurity. If researchers know what populations to target, tailored interventions can be developed to address veterans’ needs and mitigate the long-term impacts of food insecurity on health and well-being.

“There’s not a one-size-fits-all solution for addressing veteran food insecurity,” says Alicia Cohen, assistant professor (research) of family medicine and of health services, policy, and practice at Brown University. Cohen is also corresponding author of the new paper in Public Health Nutrition.

“So findings from studies like this can be used in many ways, from helping to identify the most at-risk groups to helping address veterans’ immediate food need to connecting veterans with programs and resources that can hopefully help improve their food security over the long term.”

Many veterans face economic and employment challenges following military service, Cohen says, stemming both from service-related mental and physical health issues as well difficulty reintegrating into civilian life—actors that can increase the risk of food insecurity.

Yet food insecurity is often missed in clinical settings, says Cohen, who is also a primary care provider in the women’s health clinic and homeless clinic at the Providence VA Medical Center. “You can’t tell by looking at a patient if they’re struggling to put food on the table.”

And like civilian patients, veterans often will not initiate a conversation with their health care provider about their food needs.

“If we don’t specifically ask veterans about their food needs, we are going to be missing people who are experiencing hardship,” Cohen says. “There are a number of resources within the VA and in the community to help address food insecurity, but we can’t offer these resources if we don’t know that a veteran is in need.”

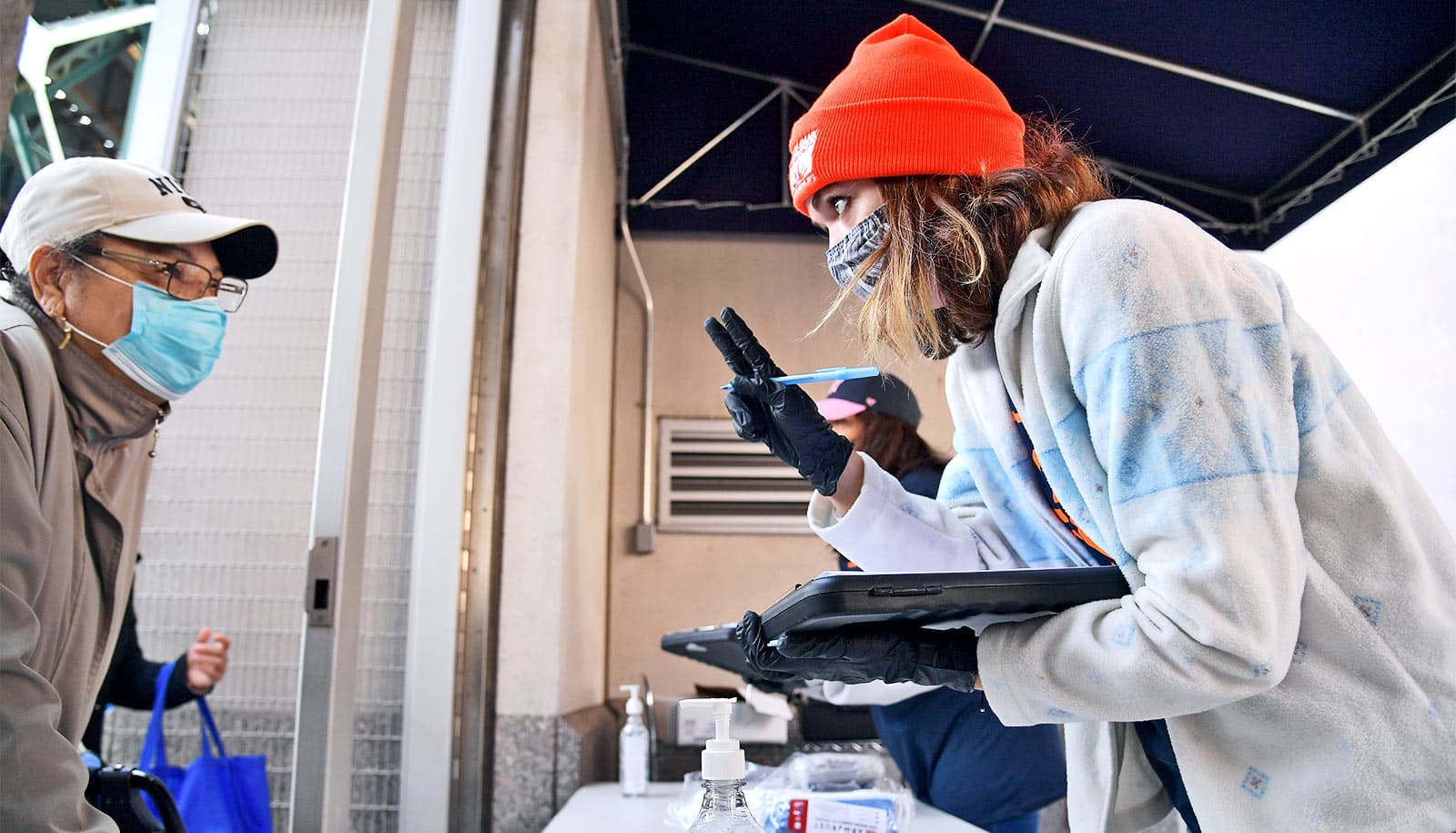

That’s one of the reasons the Veterans Health Administration developed a systematic screening system in 2017 in which staff are prompted to ask veterans seeking health care specifically about food insecurity.

Women veterans bear a ‘much higher burden’

This new study is the first to examine findings based on those screening questions. The researchers analyzed data from the screenings to identify demographic and medical characteristics associated with a positive food insecurity screen.

Between July 2017 and December 2018, 44,298 veterans screened positive for food insecurity. In their analysis, the researchers found that food insecurity was associated with identifying as non-Hispanic Black or Hispanic, non-married or partnered, and low-income. Veterans were also at higher risk for food insecurity if they had experienced homelessness or housing instability in the prior year, or if they had a diagnosis of diabetes, depression, and/or PTSD.

Prior military sexual trauma was associated with a significantly higher risk of food insecurity among both men and women. Notably, though, women screening positive for food insecurity were eight times more likely than men to have experienced military sexual trauma (49% of women vs. 6% of men).

This is a strong example of how sexual trauma experienced while in the service can have a range of serious downstream effects for veterans, Cohen says. “And as these results show, women bear a much higher burden.”

Food insecurity interventions

As a clinician who treats veterans, Cohen is familiar with how not having reliable access to nutritious food can cause serious health problems and exacerbate existing conditions. “I regularly see the negative impacts of food insecurity on my patients,” she says.

Some of the very factors that make veterans susceptible to food insecurity, like diabetes or depression, can be worsened by not having healthy food to eat, Cohen notes. The stress of not being able to afford food for oneself or one’s family compounds the situation.

The study findings can inform the development of tailored, comprehensive interventions to address food insecurity among veterans, Cohen says. For example, if a clinician is treating a veteran with diabetes who is experiencing food insecurity, they can review the patient’s medical history to see if there are any medications they might have difficulty affording or that might put the veteran at risk for low blood sugar.

In a team-based model of care, the clinician can refer the patient to a dietitian to provide nutritional counseling based on the patient’s medical and social circumstances. VA social workers can help meet a veteran’s immediate food need the day of their visit by providing a meal ticket or referring them to a food pantry, as well as provide assistance applying for any benefits for which they may qualify, such as federal food assistance programs.

The findings can also help start a conversation about refining screening practices, Cohen says. “For example, they may help us identify specific groups that would benefit from more targeted or more frequent screening for food insecurity, as well as expanding where we conduct routine food insecurity screening to include settings like mental health clinics.”

Additional coauthors are from the Providence VA Medical Center and Brown. The VA Health Services Research and Development Center of Innovation in Long Term Services and Supports, the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases funded the work.

Source: Brown University