It’s possible to use satellite data to measure the threat of climate change to ecological systems that depend on water from fog, researchers report.

Their new paper presents the first clear evidence that the relationship between fog levels and vegetation status is measurable using remote sensing.

The discovery opens up the potential to easily and rapidly assess fog’s impact on ecological health across large land masses—as compared to painstaking ground-level observation.

“It’s never been shown before that you can observe the effect of fog on vegetation from outer space,” says senior author Lixin Wang, an associate professor in the School of Science at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI).

“The ability to use the satellite data for this purpose is a major technological advance.”

The need to understand the relationship between fog and vegetation is urgent since environmental change is reducing fog levels across the globe. The shift most strongly affects regions that depend upon fog as a major source of water, including the redwood forests in California, the Atacama desert in Chile, and the Namib desert in Namibia, with the latter two currently recognized as World Heritage sites under the United Nations due to their ecological rarity.

“The loss of fog endangers plant and insect species in these regions, many of which don’t exist elsewhere in the world,” says first author Na Qiao, a visiting student at IUPUI. “The impact of fog loss on vegetation is already very clear. If we can couple this data with large-scale impact assessments based on satellite data, it could potentially influence environmental protection policies related to these regions.”

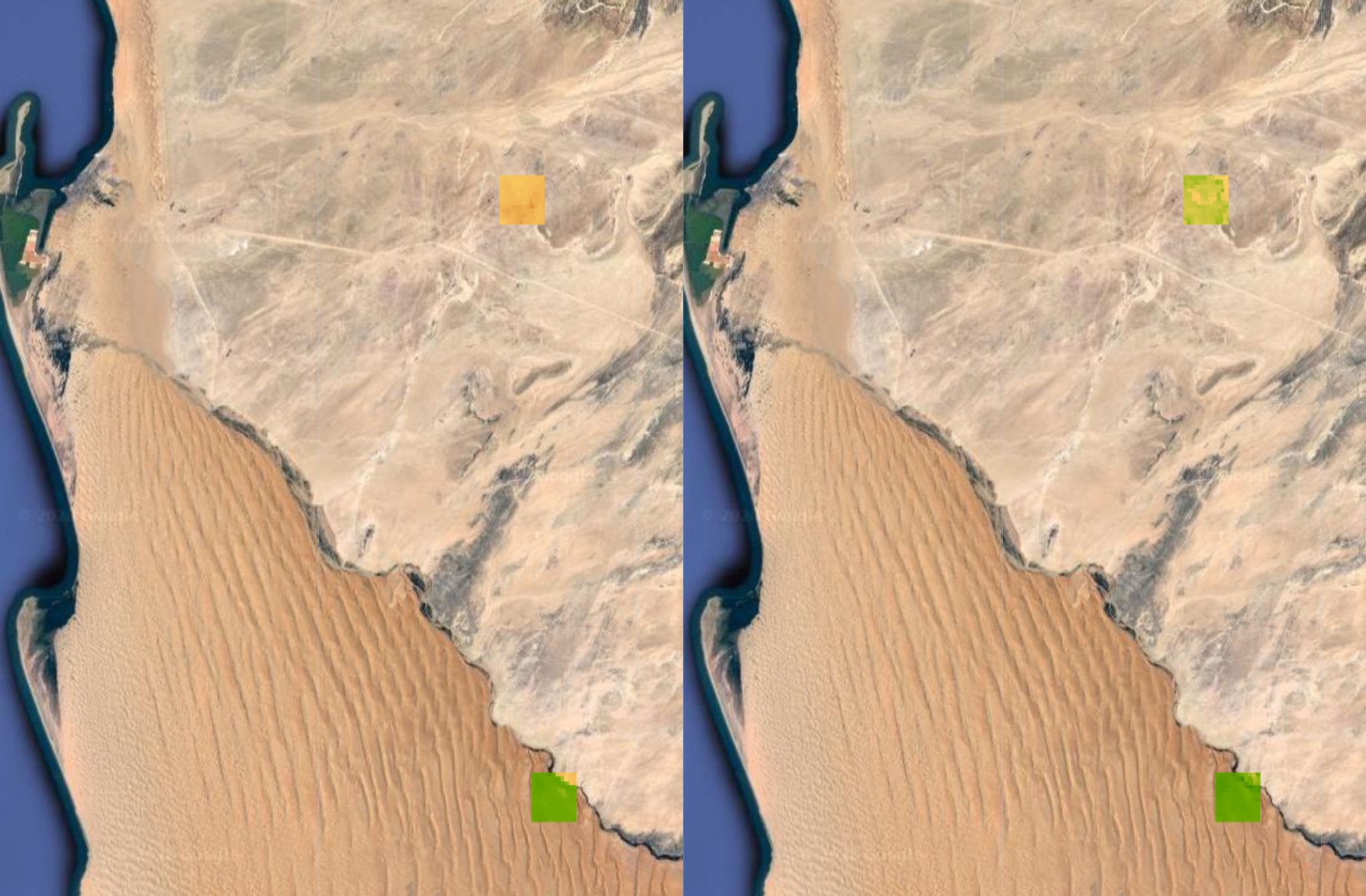

The study is based on optical and microwave satellite data, along with information on fog levels from weather stations at two locations operated by the Gobabeb Namib Research Institute in the Namib desert. The satellite data came from NASA and the US Geological Survey. The fog readings are from between 2015 and 2017.

At least once a year, Wang and student researchers, including both graduate and undergraduate students, travel to the remote facility—a two-hour drive on a dirt road from the nearest city—to conduct field research.

The researchers found a significant correlation between fog levels and vegetation status near both weather stations during the entire time of the study. Among other findings, the optical data from the site near the research facility revealed obvious signs of plant greening following fog, and up to 15% higher measures during periods of fog versus periods without fog.

Similar patterns were seen at the second site, located near a local rock formation. The microwave data also found significant correlation between fog and plant growth near the research facility, and up to 60% higher measures during periods of fog versus periods without fog.

The study’s conclusions are based on three methods of remotely measuring vegetation: two based on optical data, which is sensitive to the vibrance of greens in plants, and a third based on microwave data, which is sensitive to overall plant mass, including the amount of water in stems and leaves. Although observable by machines, the changes in vegetation color are faint enough to go undetected by the human eye.

Next, the team will build upon their current work to measure the effect of fog on vegetation over longer periods of time, which will assist with future predictions. Wang also aims to study the relationship in other regions, including the redwood forests in California.

“We didn’t even know you could use satellite data to measure the impact of fog on vegetation until this study,” he says.

“If we can extend the period under investigation, that will show an even more robust relationship. If we have 10 years of data, for example, we can make future predictions about the strength of this relationship and how this relationship has been changing over time due to climate change.”

The paper appears in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. Additional coauthors are from Indiana University, the Chinese Academy of Science, and the Gobabeb Namib Research Institute.

A National Science Foundation CAREER grant supports Wang’s work with the Gobabeb facility.

Source: Indiana University