Health experts should only replenish flu vaccines in areas that need them, researchers argue in a new paper.

More than 50 million people died in the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-19. Its 100th anniversary this flu season serves as a reminder to close flu vaccine supply gaps that may be costing hundred to thousands of lives now and could cost many more when the next “big one” strikes, researchers say.

US flu vaccine distribution logistics could use an update, says Pinar Keskinocak, chair and professor in the Georgia Institute of Technology’s H. Milton Stewart School of Industrial and Systems Engineering and director for the Center of Health and Humanitarian Systems. The new study compared the current approach with a proposed allocation method calculated to save many more lives in a pandemic or similarly intense influenza outbreak that taxes vaccine supplies.

Simple fix?

The tweak in the supply chain could also save thousands of lives annually in regular flu seasons in the US, which can be plenty deadly. A flu season can take more lives than murders in the same time period.

“Even seasonal flu kills thousands to tens of thousands of people each year, so we would benefit immediately,” says Keskinocak. “In a pandemic, nearly no one would have natural immunity, so the death toll could be significantly high if we don’t improve vaccine coverage.”

What makes a pandemic a pandemic? The flu virus represents a mutation that human immune systems have not had a chance to build prior resistance to, thus the lack of natural immunity. When the next one strikes, in addition to the many lives saved, the new recommendations could massively prevent flu infections, secondary infections like bronchitis, hospitalizations, and unnecessarily high medical costs.

Lack of logic

When a pandemic or a flu season that taxes the vaccine stocks hits, vaccine supply may become limited but then catch up over time. When that happens, vaccine distributors commonly take the population-based approach.

“Areas with larger populations get more vaccine, proportional to the population. It’s a straightforward approach that seems fair,” says co-principal investigator Julie Swann from North Carolina State University.

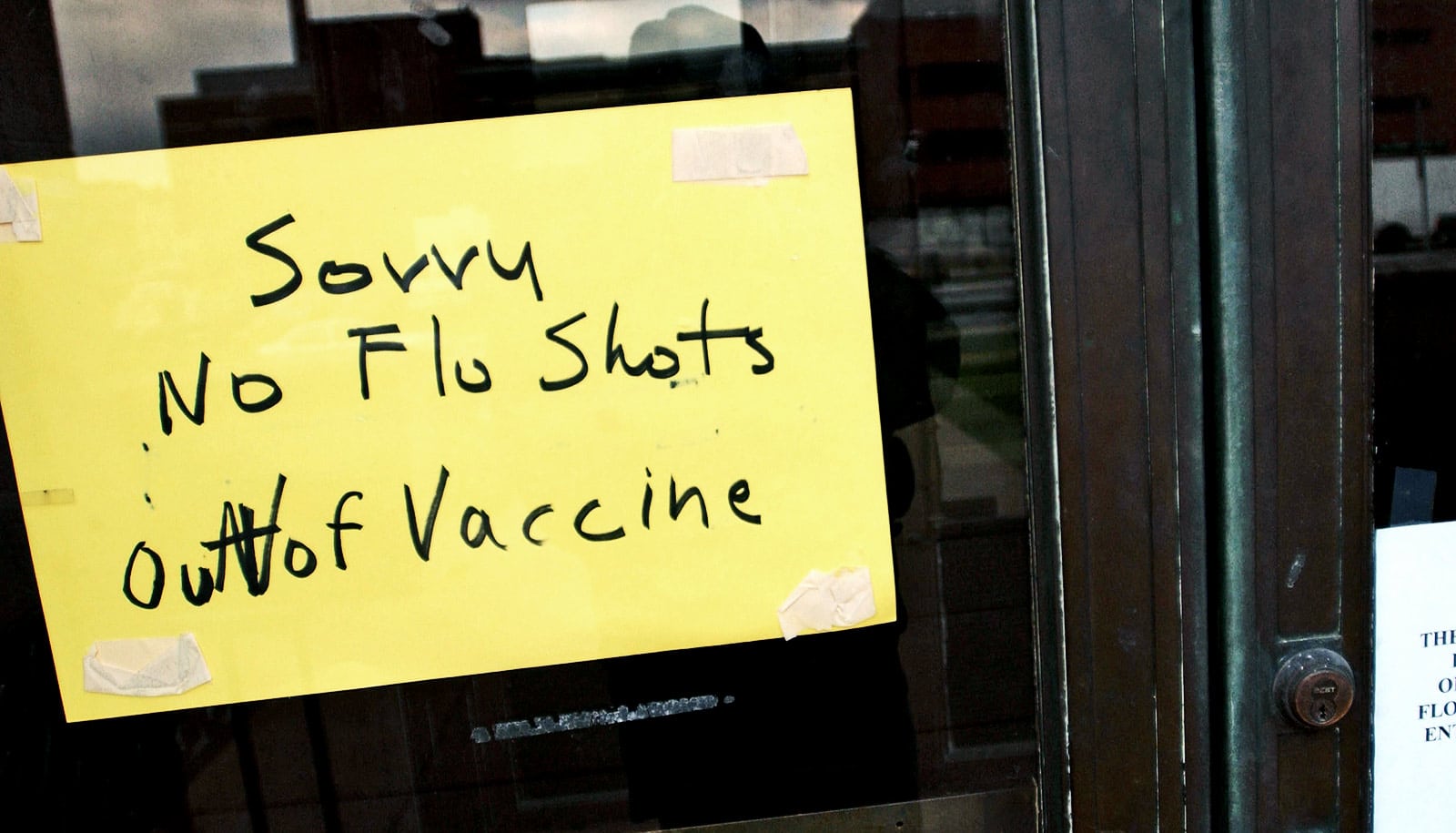

As more vaccine becomes available over time, restocking follows the same principle, and that is where distribution logic breaks down. In some regions, few people get vaccinated, but under population-based allocation, resupply stocks go there anyway and go to waste. Meanwhile, restocking may fall short of demand elsewhere, where people are lining up for inoculations.

As a result, in a pandemic, people eager for a vaccination might not get one despite adequate vaccine production, and the resulting additional unvaccinated people are more likely to get the flu and also spread it to others. That intensifies the outbreak for the entire population.

The wasted vaccine stocks also drain medical finances. The new model would relieve some of that strain even in regular flu seasons.

“Production, storage, and delivery of vaccine are costly, and unused inventory can’t just be thrown away. It costs money to dispose of,” Keskinocak says.

Restocking doses where they are actually used would boost the total number of vaccinated individuals, who would then be less likely to get sick and to infect other people and benefit the entire population. That would tamp down the flu wave for everybody.

Data for better decisions

Leftover inventory could be slashed to about 20 percent of current levels, saving considerable costs, and the data about which areas did not receive resupply could help identify areas where more people need encouragement to get vaccinated.

“The data would tell you where you need continued education about the importance of vaccination, and some of the money saved from unnecessary resupplying could be invested in public health campaigns,” says Swann, who collaborated with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention during the 2009-10 H1N1 Swine flu pandemic.

But the needed data is missing at present in the US vaccine distribution system.

“Surprisingly few states have systems in place that tell them how much vaccine has been administered where and how much is still left in inventory at provider locations,” Swann says.

Another “big one”

The next “big one” flu pandemic will sneak up on humanity someday.

If virtually everyone got a flu vaccine every year, it could cut its death toll more than half and save possibly hundreds of thousands of lives. Currently, fewer than 50 percent of Americans do.

The 1918-19 outbreak, which may have consisted of multiple concurrent influenzas, killed 678,000 people in the US. Other “big ones:” The 1957 “Asian flu” killed 116,000 in the US; the 1968 “Hong Kong flu” killed 100,000. The 2009 bird flu pandemic, which was a less contagious virus, killed 12,500 people in the US and hospitalized some 275,000.

Additional researchers are from Georgia Tech and North Carolina State University. The research appears in PLOS ONE.

The Harold R. and Mary Anne Nash Junior Faculty Endowment Fund, and the following Georgia Tech benefactors: William W. George, Andrea Laliberte, Joseph C. Mello, and Richard “Rick” E. and Charlene Zalesky supported the work. Any findings, conclusions, or recommendations are those of the author(s) and not necessarily of the funders.

Source: Georgia Tech