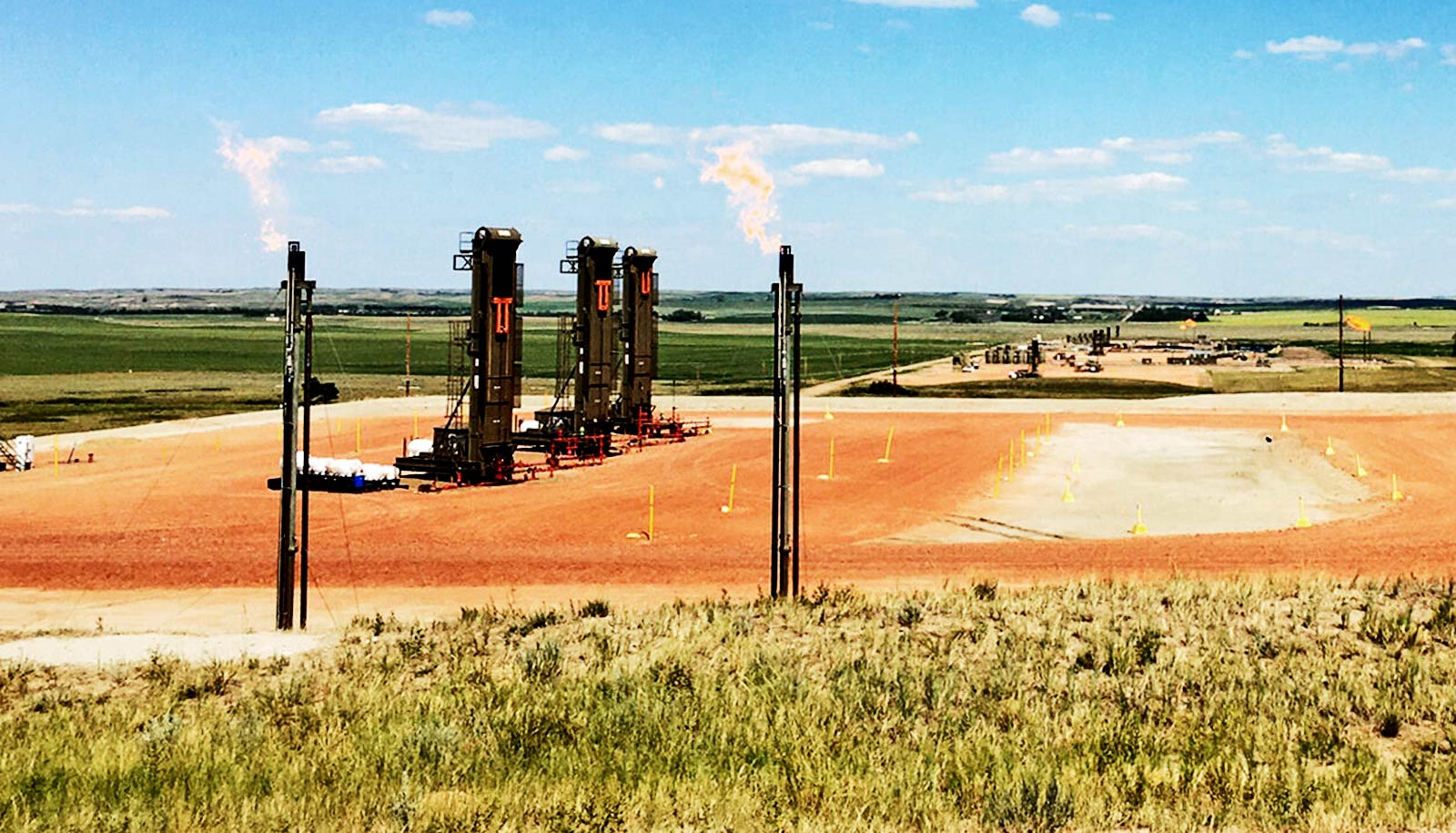

Oil and gas producers rely on flaring to limit the venting of natural gas from their facilities, but new research shows that this practice is far less effective than estimated.

The findings show that the practice releases five times more methane in the US than previously thought.

Methane is known to be a powerful greenhouse gas, but burning it off at oil and gas wells was believed to effectively keep it from escaping into the atmosphere.

Unfortunately, the data in the journal Science shows we overestimate flaring’s effectiveness and, as a result, underestimate its contribution to methane emissions and climate change. But if we fix flaring issues, the payoff is huge: the equivalent of removing 3 million cars from the roads.

Industry and regulators operate under the assumption flares are constantly lit and that they burn off 98% of methane when in operation. Data taken via aerial surveys in the three US geographical basins, which are home to more than 80% of US flaring operations, shows both assumptions are incorrect.

Researchers found flares were unlit approximately 3%-5% of the time and, even when lit, were operating at low efficiency. Combined, those factors lead to an average effective flaring efficiency rate of only 91%.

“There is a lot more methane being added to the atmosphere than currently accounted for in any inventories or estimates,” says Eric Kort, associate professor of climate and space sciences and engineering at the University of Michigan, principal investigator of the F3UEL project, and senior scientist on the new research.

Removal efficiency of flaring

Oil production can come with methane as a byproduct, and when it’s not cost-effective to capture it, the gas must be safely disposed of. Burning methane by flaring as it is released converts it to carbon dioxide, another greenhouse gas but one that is less harmful on a pound-by-pound basis.

Over the course of three years, researchers made 13 flights in planes equipped with air monitoring equipment to assess how much methane is released from flares across oil and gas production basins. Flights were conducted in the Permian and Eagle Ford oil and gas fields in Texas, as well as the Bakken oil and gas field in North Dakota.

Planes flew downwind of flaring sites—crisscrossing the direct pathways of the air plumes released by flaring. Tubes and pumps drew air into the onboard instrumentation, where laser scanning at a specific frequency measures the amount of carbon dioxide and methane it carries.

Measuring both gasses simultaneously allowed researchers to estimate the destruction removal efficiency of flaring at an individual site.

“If the flare is operating as it should be, there should be a large carbon dioxide spike and a relatively small methane spike. And depending on the relative enhancement of those two gasses, we can tell how well the flares are performing,” says lead author Genevieve Plant, an assistant research scientist in climate and space sciences and engineering.

Global Methane Pledge

In November, the US, European Union, and additional partners—103 countries in all—launched the Global Methane Pledge to restrict methane emissions. That commitment focused on keeping global temperatures within the 1.5 degree Celsius increase limit set by the scientific community to offset the worst impacts of climate change.

And last year, United Nations officials identified methane reduction as “the strongest lever we have to slow climate change over the next 25 years.”

“This appears to be a source of methane emissions that seems quite addressable,” Plant says. “With management practices and our better understanding of what’s happening to these flares, we can reduce this source of methane in a tangible way.”

Recent research led by nonprofit EDF similarly found that roughly 10% of flares are unlit or malfunctioning.

“This study adds to the growing body of research that tells us that the oil and gas industry has a flaring problem,” says Jon Goldstein, EDF’s senior director of regulatory and legislative affairs. “The Environmental Protection Agency and Bureau of Land Management should implement solutions that can help to end the practice of routine flaring.”

Additional coauthors are from Stanford University; the Environmental Defense Fund; Scientific Aviation of Boulder, Colorado; and Utrecht University’s Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research.

The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the Environmental Defense Fund, Scientific Aviation, and the University of Michigan funded the work.

Source: University of Michigan