Fishing reduces carbon sequestration in the ocean, researchers report.

A fish that dies naturally in the ocean sinks to the depths, taking with it all the carbon it contains. Yet, when a fish is caught, most of this carbon is released into the atmosphere as CO2.

The researchers estimate that because of this overlooked phenomenon, carbon emissions from fishing are actually 25% higher than what, until now, was considered to come from fuel consumption alone.

“This is the first time that we have estimated the quantity of this ‘blue carbon’ that is released into the atmosphere by fishing.”

What’s more, part of the carbon extracted from the oceans is in areas where fishing is not economically profitable in the absence of government subsidies.

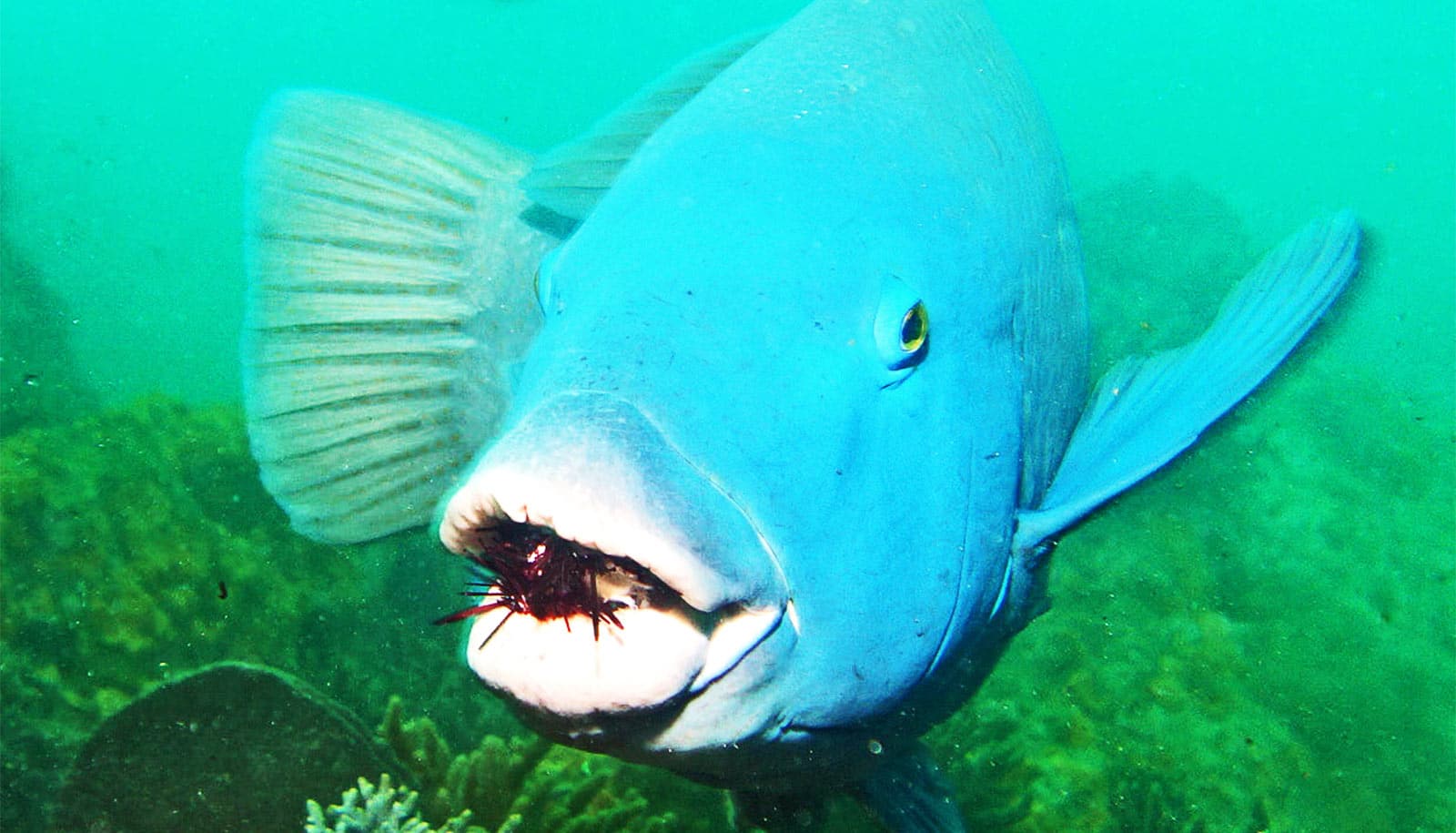

Carbon is a major component in the molecules that make up living tissue. Large fish like tuna, sharks, and swordfish are composed of 10 to 15% carbon. When they die, they quickly sink to the deep sea. As a result, most of the carbon they contain is sequestered for thousands or even millions of years. They are therefore literal carbon sinks, the size of which has never been estimated before.

This natural phenomenon, a blue carbon pump, has been greatly disrupted by industrial fishing.

“When we catch fish for our consumption, we also extract the carbon in their bodies, a fraction of which would have naturally sunk to the bottom of the ocean where it would have otherwise stayed, sequestered for many years,” says coauthor Juan Mayorga, a marine data scientist at the University of California, Santa Barbara’s Environmental Market Solutions Lab.

Scientists had never estimated the amount of carbon extracted and released into the atmosphere as a result of fishing.

“This is a step forward toward more holistic, science-based assessments of the status of fisheries management,” Mayorga says, “and opens the door to innovative financing models including tapping into carbon markets.”

Industrial fishing therefore emits CO2 into the atmosphere in two ways: not only do the boats massively emit greenhouse gases by consuming fuel oil, but in addition, by extracting fish from the sea, they release CO2 which would otherwise remain captive in the ocean.

“This is the first time that we have estimated the quantity of this ‘blue carbon’ that is released into the atmosphere by fishing,” explains coauthor David Mouillot, a professor at the University of Montpellier. This estimate is far from negligible since researchers consider this carbon sequestration deficit in the deep ocean would represent more than 25% of the previous carbon balance of industrial fishing activities.

The findings imply that estimates of carbon emissions from industrial fishing should be revised upwards.

“Three quarters of these real emissions are related to fuel consumption, and one quarter comes from the fact that the carbon contained in the fish caught is released as CO2 into the atmosphere instead of remaining buried in the seabed,” the researchers say.

For the authors of the study, these new data bring another strong argument in favor of more reasoned fishing: “The annihilation of the blue carbon pump represented by these large fish suggests that new protection and management measures must be put in place, so that more large fish can remain a carbon sink and no longer become an additional CO2 source,” says lead author Gaël Mariani, a doctoral student at the University of Montpellier.

Above all, we need to fish better, adds Mouillot. Fishing boats sometimes go to very remote areas, which causes enormous fuel consumption, even though the fish caught in these areas are not profitable and fishing is only viable thanks to subsidies. Researchers estimate that 43.5% of this “blue carbon” extracted by fishing comes from such areas.

“We do not have to stop fishing to regain many of these carbon sequestration benefits,” says coauthor Steve Gaines, director of the Bren School of Environmental Science & Management at UC Santa Barbara. “If we fish in the right places and at sustainable rates, we can rebuild a significant amount of this natural blue carbon sink.”

The study appears in Science Advances.

Source: UC Santa Barbara