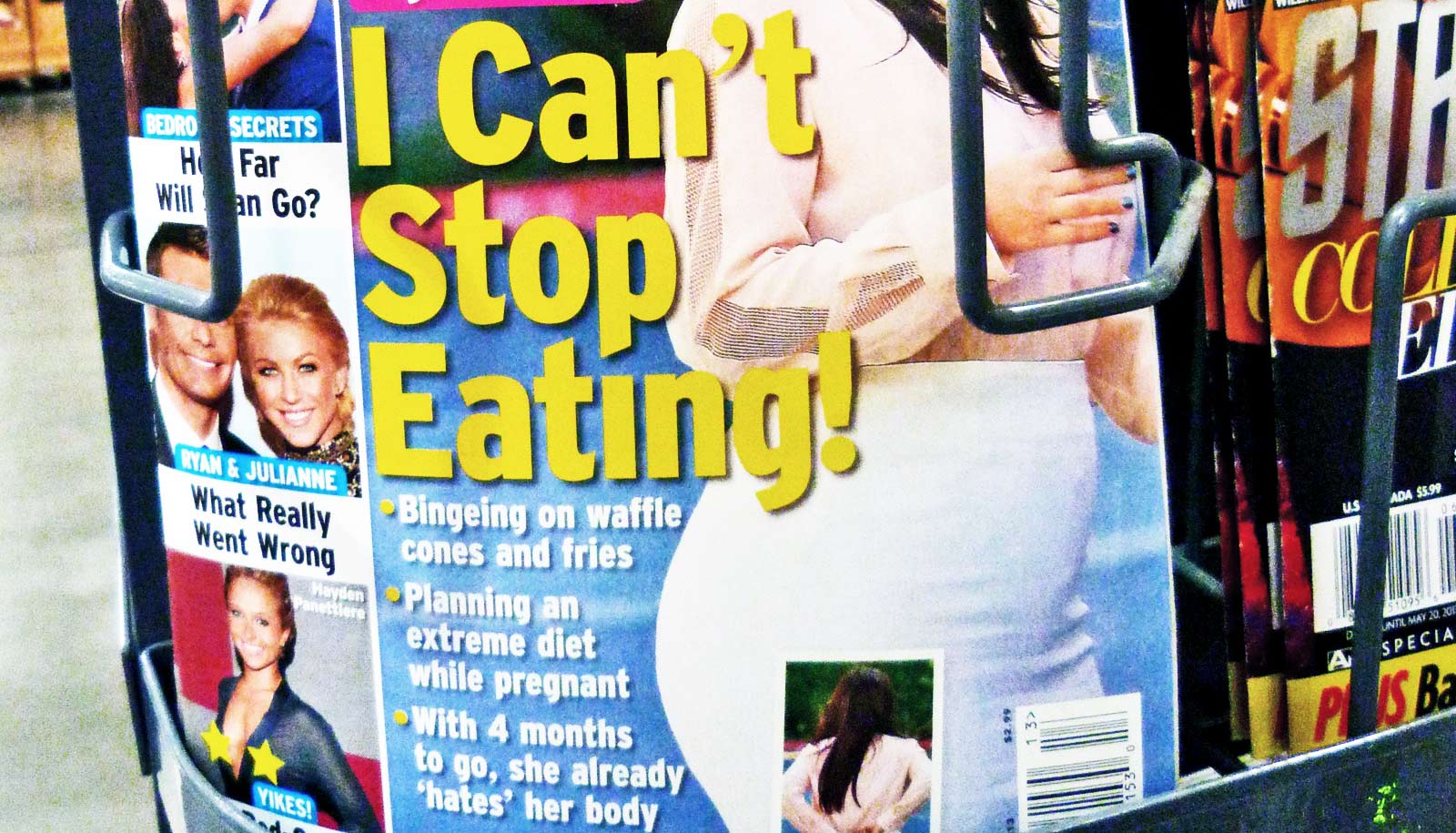

New research links celebrity fat-shaming—critiques of their appearance—with increased implicit negative weight-related attitudes among women.

“These cultural messages appeared to augment women’s gut-level feeling that ‘thin’ is good and ‘fat’ is bad,” says study coauthor Jennifer Bartz, of the psychology department at McGill University. “These media messages can leave a private trace in peoples’ minds.”

Explicit attitudes are those that people consciously endorse and, based on other research, are often influenced by concerns about social desirability and presenting oneself in the most positive light. By contrast, implicit attitudes—which were the focus of this investigation—reflect people’s split-second gut-level reactions that something is inherently good or bad.

The research also finds that from 2004 to 2015, implicit weight bias was on the rise more generally.

Bartz and her colleagues obtained data from Project Implicit of participants who completed the online Weight Implicit Association Test from 2004 to 2015. The team selected 20 celebrity fat-shaming events in the popular media, including Tyra Banks being shamed for her body in 2007 while wearing a swimsuit on vacation and Kourtney Kardashian’s husband fat-shaming her for not losing weight faster after pregnancy in 2014.

They analyzed women’s implicit anti-fat attitudes two weeks before and two weeks after each celebrity fat-shaming event.

Examining the results, the fat-shaming events led to a spike in women’s implicit anti-fat attitudes, with more “notorious” events producing greater spikes.

While the researchers cannot definitively link an increase in implicit weight bias to specific negative incidents in the real world with their data, other research has shown culture’s emphasis on the thin ideal can contribute to eating disorders, which are particularly prevalent among young women.

“Weight bias is recognized as one of the last socially acceptable forms of discrimination; these instances of fat-shaming are fairly wide-spread not only in celebrity magazines but also on blogs and other forms of social media,” says Amanda Ravary, PhD student and lead author of the study.

The researchers’ next steps include lab research, where they can manipulate exposure to fat-shaming messages (vs. neutral messages) and assess the effect of these messages on women’s implicit anti-fat attitudes. This future research could provide more direct evidence for the causal role of these cultural messages on people’s implicit attitudes.

The research appears in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. Funding came from les Fonds de recherche du Québec- Société et culture.

Source: McGill University