Neuroscientists have discovered a group of cells in the brain that cause frightening memories to re-emerge unexpectedly.

The finding could lead to new recommendations about when and how often doctors deploy certain therapies for the treatment of anxiety, phobias, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

In the new paper, which appears in the journal Nature Neuroscience, researchers describe identifying “extinction neurons,” which suppress fearful memories when they’re active or allow fearful memories to return when they’re not.

Since the time of Pavlov and his dogs, scientists have known that memories we thought we had put behind us can pop up at inconvenient times, triggering what is known as spontaneous recovery, a form of relapse. What they didn’t know was why it happened.

“There is frequently a relapse of the original fear, but we knew very little about the mechanisms,” says senior author Michael Drew, associate professor of neuroscience at the University of Texas at Austin. “These kinds of studies can help us understand the potential cause of disorders, like anxiety and PTSD, and they can also help us understand potential treatments.”

Fear and memory

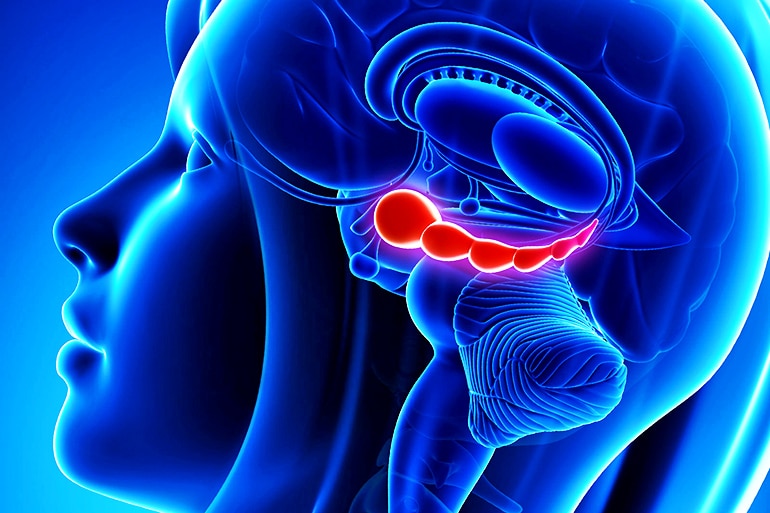

One of the surprises to Drew and his team was finding that brain cells that suppress fear memories hid in the hippocampus. Traditionally, scientists associate fear with another part of the brain, the amygdala. The hippocampus, responsible for many aspects of memory and spatial navigation, seems to play an important role in contextualizing fear, for example, by tying fearful memories to the place where they happened.

The discovery may help explain why one of the leading ways to treat fear-based disorders, exposure therapy, sometimes stops working. Exposure therapy promotes the formation of new memories of safety that can override an original fear memory. For example, if someone becomes afraid of spiders after a bite, he might undertake exposure therapy by letting a harmless spider crawl on him. The safe memories are called “extinction memories.”

“Extinction does not erase the original fear memory but instead creates a new memory that inhibits or competes with the original fear,” Drew says. “Our paper demonstrates that the hippocampus generates memory traces of both fear and extinction, and competition between these hippocampal traces determines whether fear is expressed or suppressed.”

Given this, recommended practices around the frequency and timing of exposure therapy may need revisiting, and researchers may be able to explore new pathways for drug development.

Suppressing fear

In experiments, Drew and his team placed mice in a distinctive box and induced fear with a harmless shock. After that, when one of the mice was in the box, it would display fear behavior until, with repeated exposure to the box without a shock, the extinction memories formed, and the mouse was not afraid.

Scientists were able to artificially activate the fear and suppress the extinction trace memories by using a tool called optogenetics to turn the extinction neurons on and off again.

“Artificially suppressing these so-called extinction neurons causes fear to relapse, whereas stimulating them prevents fear relapse,” Drew says. “These experiments reveal potential avenues for suppressing maladaptive fear and preventing relapse.”

Additional researchers from the University of Texas and Columbia University contributed to the work. Funding for the research came from the National Institutes of Health and the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology.

Source: University of Texas at Austin