One in three species of all plants and animals may face extinction by 2070, according to a new study based on data from hundreds of species around the globe.

Accurately predicting biodiversity loss from climate change requires a detailed understanding of what aspects of climate change cause extinctions, and what mechanisms may allow species to survive, researchers say.

The new study presents detailed estimates of global extinction from climate change by 2070. Researchers combined information on recent extinctions from climate change, rates of species movement, and different projections of future climate to estimate that one in three species of plants and animals may face extinction by 2070.

Appearing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the study likely is the first to incorporate data from recent climate-related extinctions and from rates of species movements to estimate broad-scale extinction patterns from climate change.

Escaping rising temperatures

To estimate the rates of future extinctions from climate change, Cristian Román-Palacios and John J. Wiens, both in the ecology and evolutionary biology department at the University of Arizona, looked to the recent past. Specifically, they examined local extinctions that have already happened, based on studies of repeated surveys of plants and animals over time.

The researchers analyzed data from 538 species and 581 sites around the world, focusing on plant and animal species surveyed at the same sites over time, at least 10 years apart. They generated climate data from the time of the earliest survey of each site and the more recent survey. They found that 44% of the 538 species had already gone extinct at one or more sites.

“By analyzing the change in 19 climatic variables at each site, we could determine which variables drive local extinctions and how much change a population can tolerate without going extinct,” Román-Palacios says.

“We also estimated how quickly populations can move to try and escape rising temperatures. When we put all of these pieces of information together for each species, we can come up with detailed estimates of global extinction rates for hundreds of plant and animal species.”

The study identified maximum annual temperatures—the hottest daily highs in summer—as the key variable that best explains whether a population will go extinct. Surprisingly, the researchers found that average yearly temperatures showed smaller changes at sites with local extinction, even though research widely uses average temperatures as a proxy for overall climate change.

“This means that using changes in mean annual temperatures to predict extinction from climate change might be positively misleading,” Wiens says.

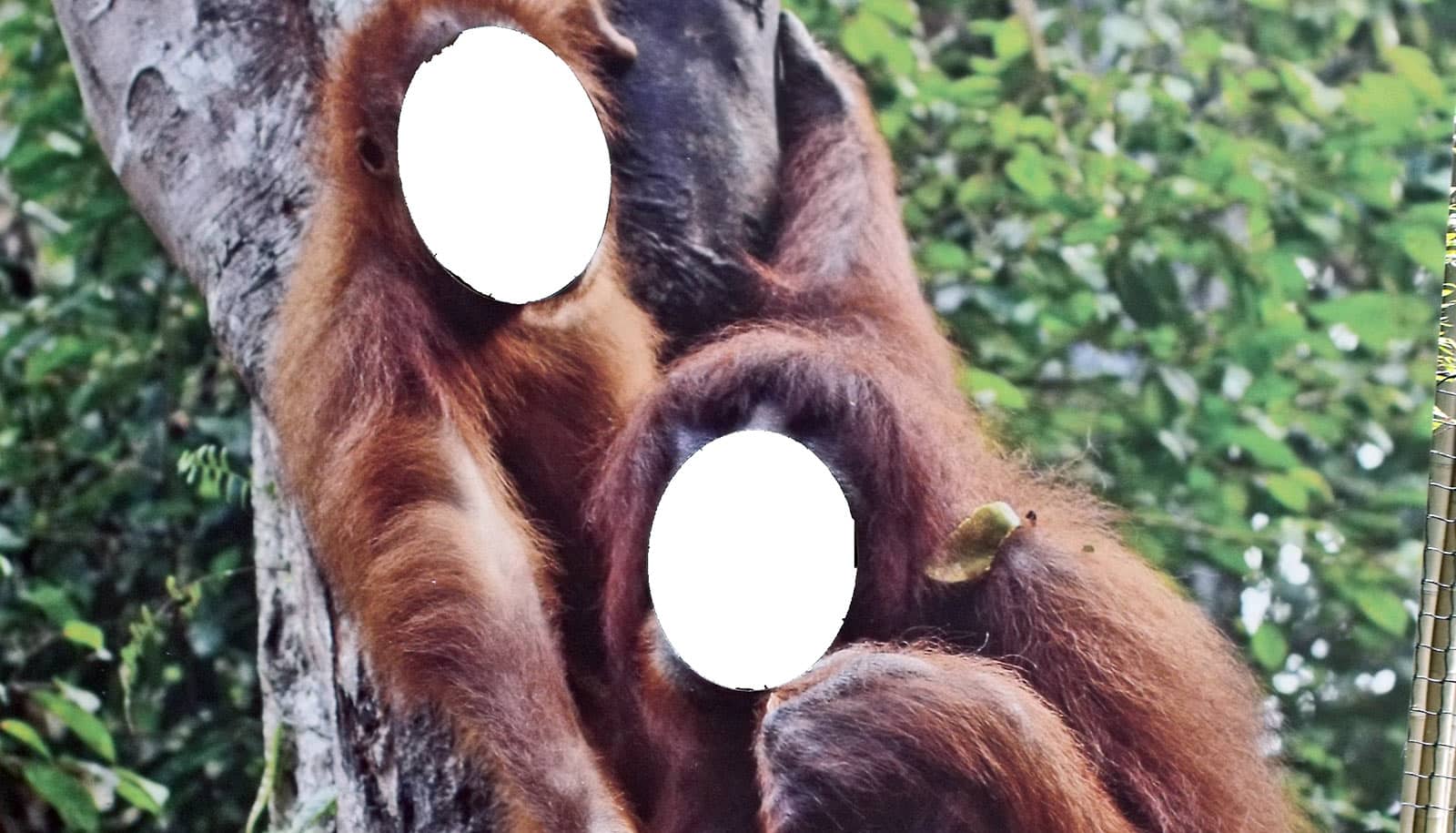

Worse extinction risk in the tropics

Previous studies have focused on dispersal—or migration to cooler habitats—as a means for species to “escape” from warming climates.

However, the authors of the current study found that most species will not be able to disperse quickly enough to avoid extinction, based on their past rates of movement.

Instead, many species may tolerate some increases in maximum temperatures, but only up to a point. They found that about 50% of the species had local extinctions if maximum temperatures increased by more than 0.5 degrees Celsius, and 95% if temperatures increase by more than 2.9 degrees Celsius.

Projections of species loss depend on how much climate will warm in the future, the researchers say.

“In a way, it’s a ‘choose your own adventure,'” Wiens says. “If we stick to the Paris Agreement to combat climate change, we may lose fewer than 2 out of every 10 plant and animal species on Earth by 2070. But if humans cause larger temperature increases, we could lose more than a third or even half of all animal and plant species, based on our results.”

The paper’s projections of species loss are similar for plants and animals, but extinctions are projected to be two to four times more common in the tropics than in temperate regions.

“This is a big problem, because the majority of plant and animal species occur in the tropics,” Román-Palacios says.

Source: University of Arizona