In a genetic surprise, ancient DNA shows the closest family members of an extinct bird from the Caribbean known as the Haitian cave-rail are not in the Americas, but Africa and the South Pacific.

The findings uncover an unexpected link between Caribbean bird life and the Old World.

Like many animals unique to the Caribbean, cave-rails became extinct soon after people settled the islands. The last of three known West Indian species of cave-rails—flightless, chicken-sized birds—vanished within the past 1,000 years.

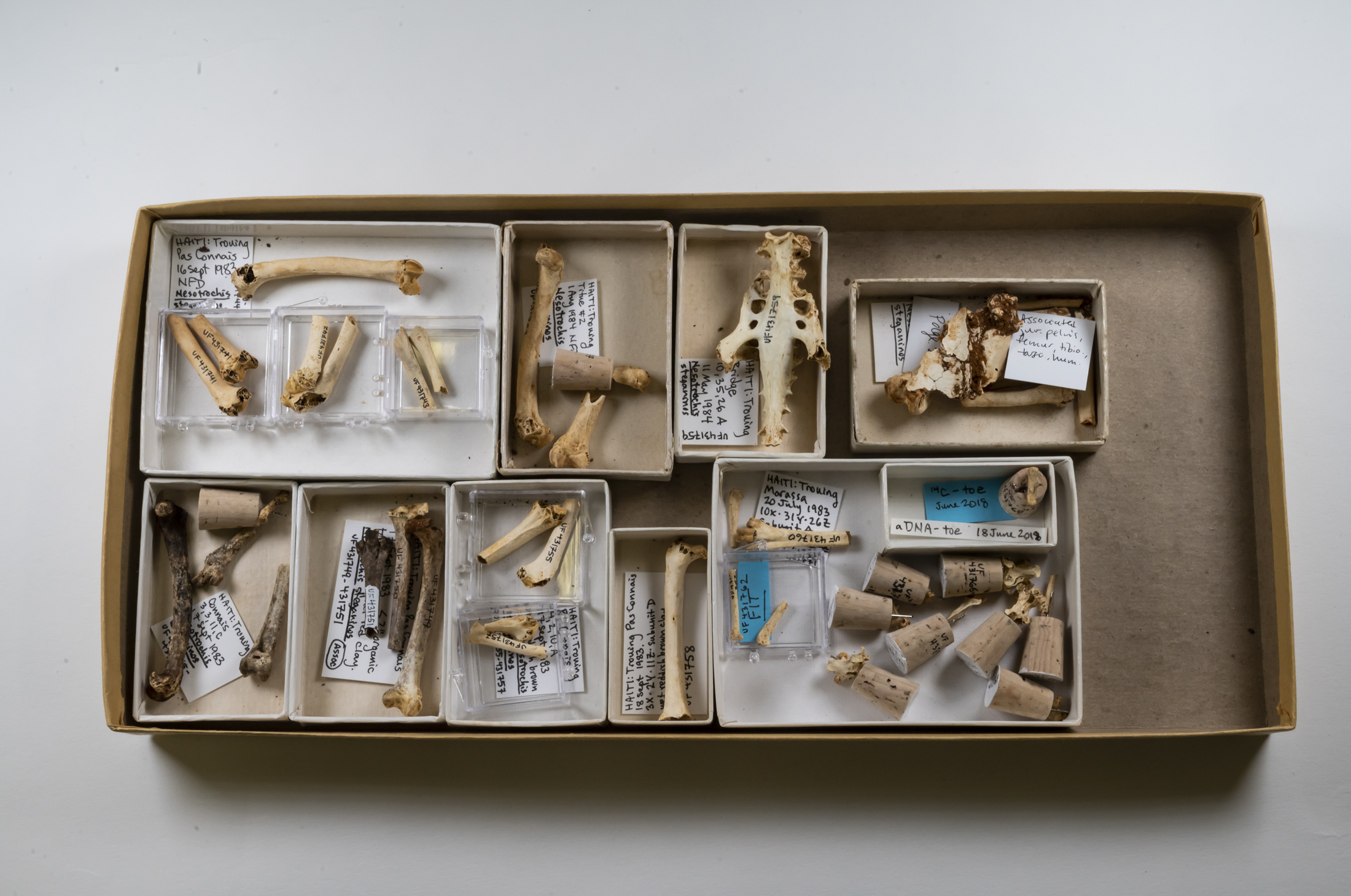

Researchers analyzed DNA from a fossil toe bone of the Haitian cave-rail, Nesotrochis steganinos, to resolve the group’s long-debated ancestry.

But they were unprepared for the results: The genus Nesotrochis is most closely related to the flufftails, flying birds that live in sub-Saharan Africa, Madagascar, and New Guinea, and the adzebills, large, extinct, flightless birds native to New Zealand.

Evolutionary whodunit

The study, published in Biology Letters, presents the first example of a Caribbean bird whose closest relatives live in the Old World, showcasing the power of ancient DNA to reveal a history humans have erased.

The discovery was “just mind-blowing,” says study lead author Jessica Oswald, who began the project as a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Florida’s Florida Museum of Natural History.

“If this study had not happened, we might still be under the assumption that the closest relatives of most things in the Caribbean are on the mainland in the Americas,” says Oswald, now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Nevada, Reno and a Florida Museum research affiliate. “This gives us an understanding of the region’s biodiversity that would otherwise be obscured.”

Many animals evolved unusual forms on islands, often making it difficult to classify extinct species based on their physical characteristics alone. But advancements in extracting viable DNA from fossils now enables scientists to answer longstanding questions with ancient genetic evidence.

Oswald describes her work as similar to a forensic investigation, piecing together fragmented, degraded genetic material to trace the evolutionary backstory of extinct animals.

“Understanding where all of these extinct species fit into a larger family tree or evolutionary history gives us insight into what a place looked like before people arrived,” she says. “That’s why my job is so fun. It’s always this whodunit.”

Haitian cave-rail isn’t a rail at all

Oswald was just starting her ancient DNA work at the Florida Museum when study coauthor David Steadman, curator of ornithology, suggested the Haitian cave-rail as a good candidate for analysis.

Cave-rails share physical characteristics with several types of modern birds, and scientists have conjectured for decades whether they are most closely related to wood rails, coots, or swamphens—birds that all belong to the rail family, part of a larger group known as the Gruiformes. Oswald and Steadman hoped that studying cave-rail DNA would clarify “what the heck this thing is,” Oswald says.

When preliminary results indicated the species had a trans-Atlantic connection, Steadman, who has worked in the Caribbean for more than 40 years, was skeptical.

“Being flightless and plump was not a great strategy during human colonization of the Caribbean.”

The genetics also showed that the cave-rail isn’t a rail at all: While flufftails and adzebills are also members of the Gruiformes, they are in separate families from rails.

“It just didn’t seem logical that you’d have to go across the Atlantic to find the closest relative,” Steadman says. “But the fact that people had a hard time classifying where Nesotrochis was within the rails—in hindsight, maybe that should have been a clue. Now I have a much more open mind.”

One reason the cave-rail was so difficult to classify is that when birds lose the ability to fly, they often converge on a similar body plan, Steadman says. Flightlessness is a common adaptation in island birds, which face far fewer predators in the absence of humans and invasive species such as dogs, cats, rats, and pigs.

“You don’t have to outfly or outrun predators, so your flying and running abilities become reduced,” Steadman says. “Because island birds spend less energy avoiding predators, they also tend to have a lower metabolic rate and nest on the ground. It’s no longer life in the fast lane. They’re essentially living in a Corona commercial.”

While sheltered from the mass extinctions that swept the mainland, cave-rails became helpless once people touched foot on the islands, having lost their defenses and cautiousness.

“Being flightless and plump was not a great strategy during human colonization of the Caribbean,” says study coauthor Robert Guralnick, Florida Museum curator of biodiversity informatics.

Clues in ancient DNA

How did cave-rails get to the Caribbean in the first place? Monkeys and capybara-like rodents journeyed from Africa to the New World about 25-36 million years ago, likely by rafting, and cave-rails may also have migrated during that time span, Steadman says.

“Humans have meddled so much in the region and caused so many extinctions, we need ancient DNA to help us sort out what’s related to what.”

He and Oswald envision two probable scenarios: The ancestors of cave-rails either made a long-distance flight across an Atlantic Ocean that was not much narrower than today, or the group was once more widespread across the continents, with more relatives remaining to be discovered in the fossil record.

Other researchers have recently published findings that corroborate the story told by cave-rail DNA: A study of foot features suggested Nesotrochis could be more closely related to flufftails than rails, and other research showed that adzebills are close relatives of the flufftails. Like cave-rails, adzebills are also an example of a flightless island bird extinguished by human hunters.

“Humans have meddled so much in the region and caused so many extinctions, we need ancient DNA to help us sort out what’s related to what,” Oswald says.

The findings also underscore the value of museum collections, Steadman says. The toe bone Oswald used in her analysis was collected in 1983 by Charles Woods, then the Florida Museum’s curator of mammals. At that time, “nobody was thinking about ancient DNA,” Steadman says. “It shows the beauty of keeping things well curated in a museum.”

Additional coauthors are from Occidental College, the University of Nevada, Reno, the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and the Florida Museum. The National Science Foundation and the Florida Museum funded the work.

Source: University of Florida