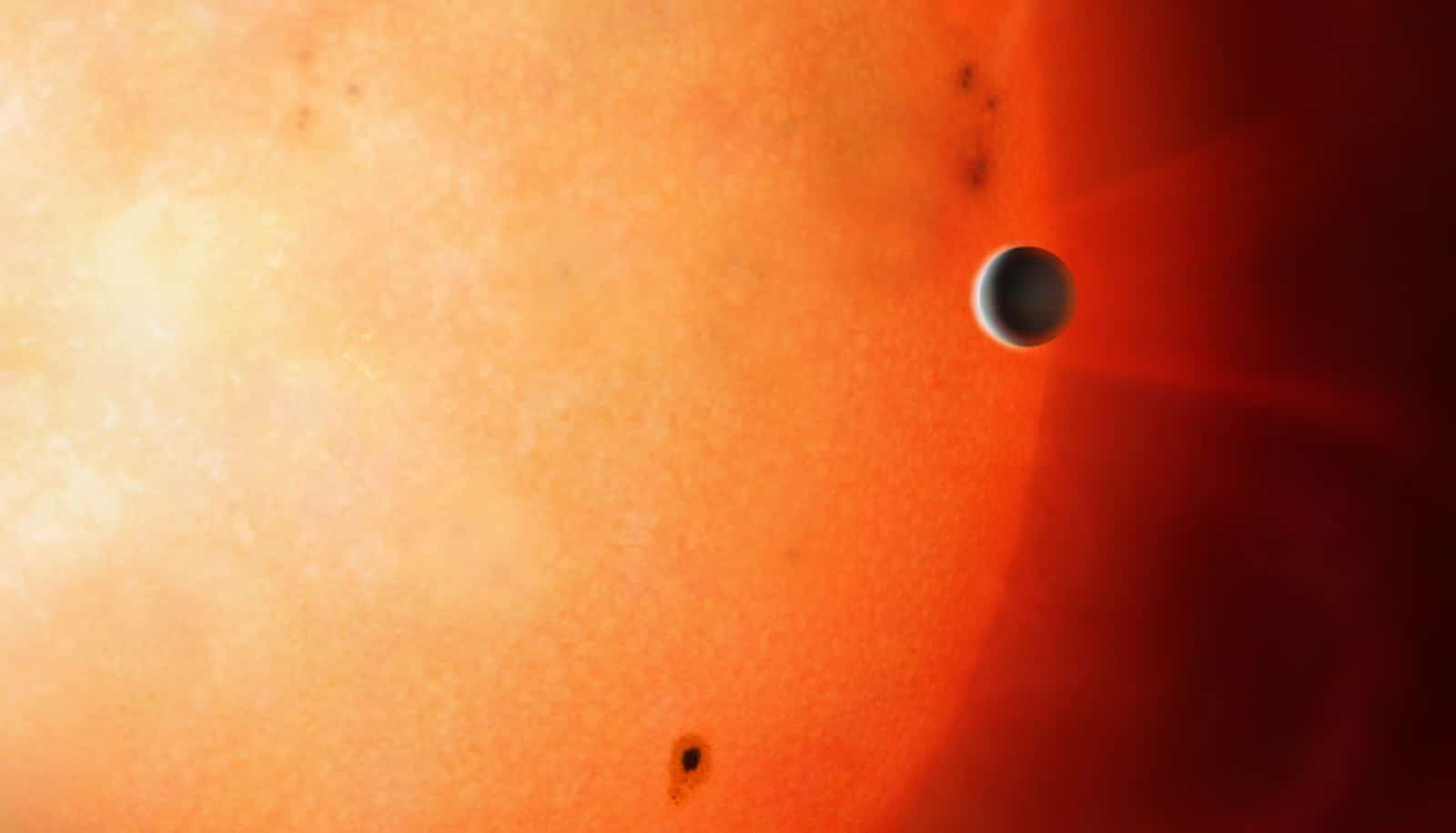

Astronomers have observed the exoplanet NGTS-10b orbiting a star in just over 18 hours, the shortest orbital period ever observed for a planet of its type.

It means that a single year for this hot Jupiter—a gas giant similar in size and composition to Jupiter in our own solar system—passes in less than a day of Earth time.

The discovery appears in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society and the scientists believe that it may help to solve a mystery of whether or not such planets are in the process of spiraling towards their suns to their destruction.

“Over the next ten years, it might be possible to see this planet spiraling in,” says study coauthor Daniel Bayliss of the University of Warwick’s physics department. “We’ll be able to use NGTS to monitor this over a decade. If we could see the orbital period start to decrease and the planet start to spiral in, that would tell us a lot about the structure of the planet that we don’t know yet.

“Everything that we know about planet formation tells us that planets and stars form at the same time. The best model that we’ve got suggests that the star is about 10 billion years old and we’d assume that the planet is too. Either we are seeing it in the last stages of its life, or somehow it’s able to live here longer than it should.”

The discovery of exoplanet NGTS-10b

The planet NGTS-10b was discovered around 1,000 light years away from Earth as part of the Next-Generation Transit Survey (NGTS), an exoplanet survey based in Chile that aims to discover planets down to the size of Neptune using the transit method. This involves observing stars for a telltale dip in brightness that indicates that a planet has passed in front of it.

At any one time the survey observes 100 square degrees of sky which includes around 100,000 stars. Out of those 100,000 stars, this one caught the astronomers’ eyes due to the very frequent dips in the star’s light caused by the planet’s rapid orbit.

“We’re excited to announce the discovery of NGTS-10b, an extremely short period Jupiter-sized planet orbiting a star not too dissimilar from our sun,” says lead author James McCormac.

“Although in theory hot Jupiters with short orbital periods (less than 24 hours) are the easiest to detect due to their large size and frequent transits, they have proven to be extremely rare. Of the hundreds of hot Jupiters currently known there are only seven that have an orbital period of less than one day.”

Locked in place

NGTS-10b orbits so rapidly because it is very close to its sun—only twice the diameter of the star that, in the context of our solar system, would locate it 27 times closer than Mercury is to our own sun. The scientists have noted that it is perilously close to the point that tidal forces from the star would eventually tear the planet apart.

The planet is likely tidally locked so one side of the planet is constantly facing the star and constantly hot—the astronomers estimate the average temperature to be more than 1,000 degrees Celsius (1,832 degrees Fahrenheit). The star itself is around 70% the radius of our sun and 1,000 degrees cooler. NGTS-10b is also an excellent candidate for atmospheric characterization with the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope.

Using transit photometry, the scientists know that the planet is 20% bigger than our Jupiter and just over twice the mass according to radial velocity measurements, caught at a convenient point in its lifecycle to help answer questions about the evolution of such planets.

Soon to spiral to its death?

Massive planets typically form far away from the star and then migrate either through interactions with the disc while the planet is still forming, or from interactions with additional planets much further out later in their life.

The astronomers plan to apply for time to get high-precision measurements of NGTS-10b, and to continue observing it over the next decade to determine whether this planet will remain in this orbit for some time to come—or will spiral into the star to its death.

NGTS is situated at the European Southern Observatory’s Paranal Observatory in the heart of the Atacama Desert, Chile. It is a collaboration among UK Universities Warwick, Leicester, Cambridge, and Queen’s University Belfast, together with Observatoire de Genève, DLR Berlin, and Universidad de Chile. In the UK, the facility and the research have support from the Science and Technologies Facilities Council (STFC) part of UK Research and Innovation (UKRI).

Source: University of Warwick