The exoplanet Fomalhaut b in a nearby star system likely never existed, say astronomers.

Their analysis points to a vast, expanding cloud of dust instead—likely from a cosmic collision.

“Clearly, Fomalhaut b was doing things a bona fide planet should not be doing.”

The astronomers conclude that NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope was looking at an expanding cloud of very fine dust particles from two icy bodies that smashed into each other. Hubble came along too late to witness the suspected collision but may have captured its aftermath. The missing-in-action planet was last seen orbiting the star Fomalhaut, 25 light years away.

“These collisions are exceedingly rare and so this is a big deal that we actually get to see evidence of one,” says András Gáspár, an assistant astronomer at the University of Arizona’s Steward Observatory and lead author of a research paper announcing the discovery. “We believe that we were at the right place at the right time to have witnessed such an unlikely event with NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope.”

“The Fomalhaut star system is the ultimate test lab for all of our ideas about how exoplanets and star systems evolve,” adds George Rieke, professor of astronomy at Steward Observatory. “We do have evidence of such collisions in other systems, but none of this magnitude has been observed in our solar system. This is a blueprint of how planets destroy each other.”

Fomalhaut-b was strange

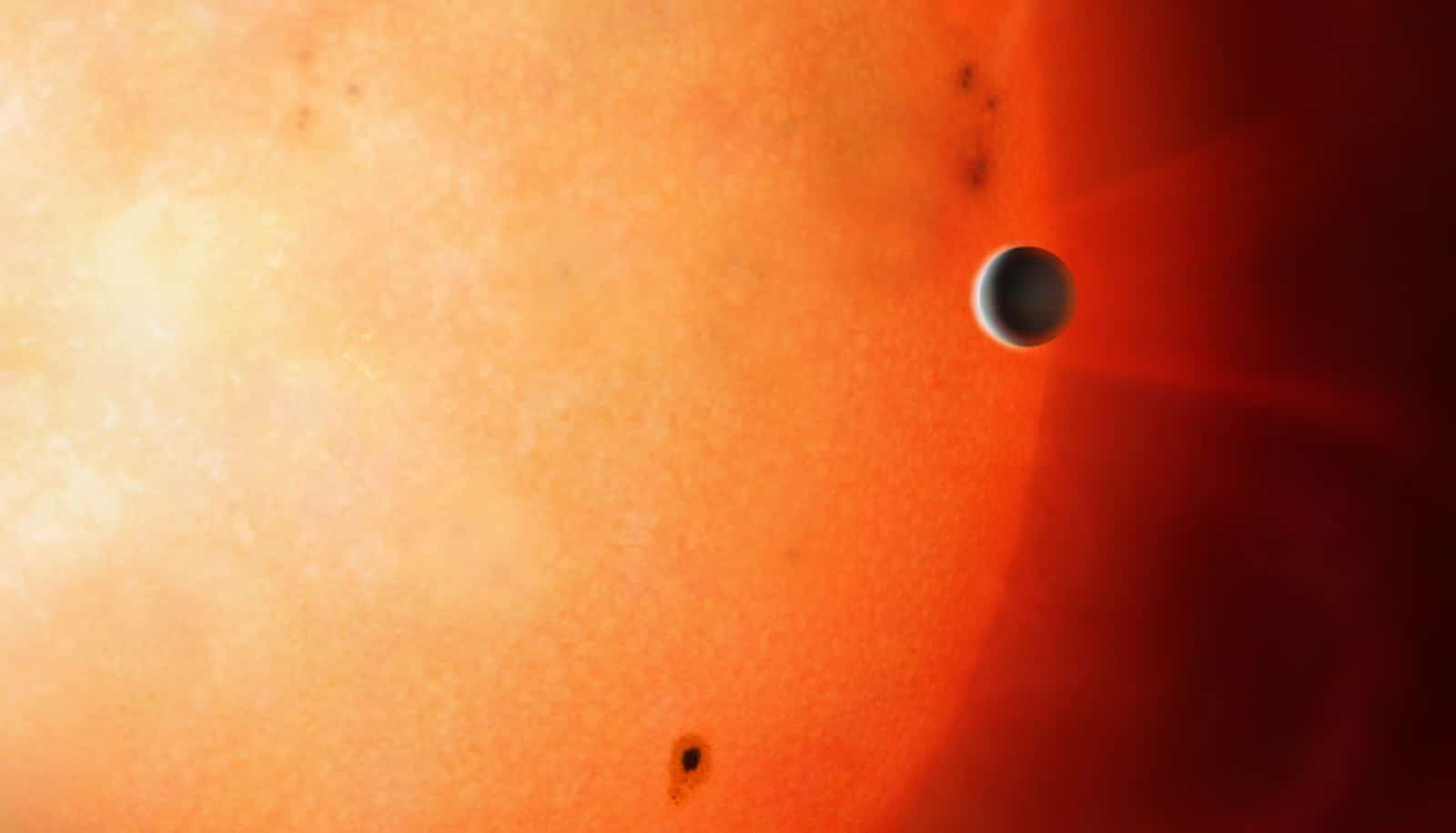

The suspected exoplanet, named Fomalhaut b, was first announced in 2008, based on data from 2004 and 2006. It was clearly visible in several years of Hubble observations, which revealed it was a moving dot. Until then, evidence for exoplanets had mostly been inferred through indirect detection methods, such as subtle back-and-forth stellar wobbles and shadows from planets passing in front of their stars.

Unlike other directly imaged exoplanets, however, puzzles arose with Fomalhaut b. The object was bright in visible light—highly unusual for an exoplanet, which is simply too small to reflect enough light from its host star to be seen from Earth. At the same time, it did not have any detectable infrared heat signature—again, highly unusual, as a planet should be warm enough to shine in the infrared, especially a young one like Fomalhaut b. Astronomers conjectured that the added brightness came from a huge shell or ring of dust encircling the planet that may have been collision-related.

“Our study, which analyzed all available archival Hubble data on Fomalhaut, revealed several characteristics that together paint a picture that the planet-sized object may never have existed in the first place,” Gáspár says.

The team emphasizes that the final nail in the coffin came when their data analysis of Hubble images taken in 2014 showed the object had vanished, to their disbelief. Adding to the mystery, earlier images showed the object to continuously fade over time, they say.

“Clearly, Fomalhaut b was doing things a bona fide planet should not be doing,” Gáspár says.

Dust cloud

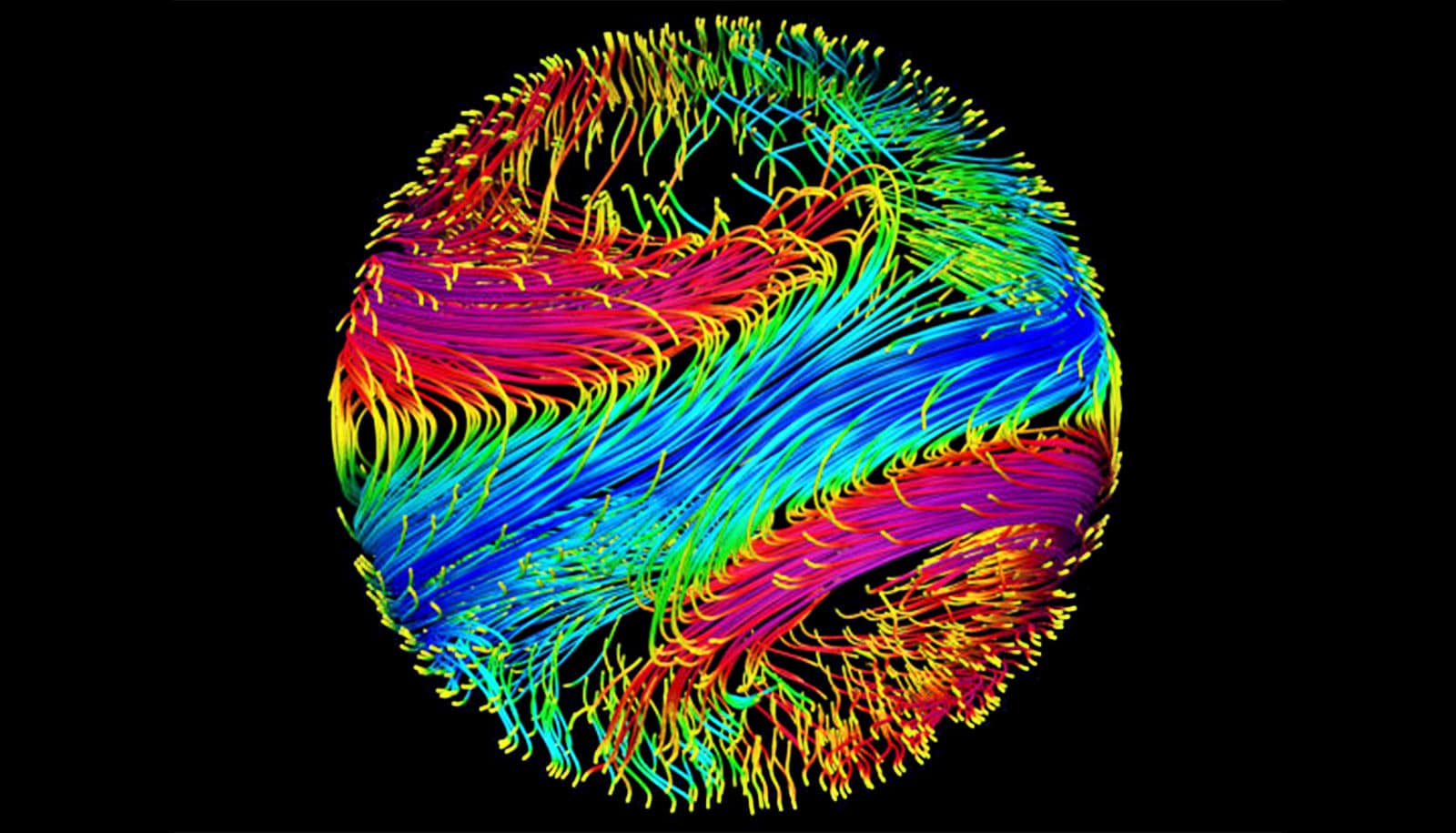

The interpretation is that Fomalhaut b is slowly expanding from the smashup that blasted a dissipating dust cloud into space. Taking into account all available data, Gáspár and Rieke think the collision occurred not too long prior to the first observations taken in 2004. By now, the debris cloud—consisting of dust particles around 1 micron in size, or about 1/50th the diameter of a human hair—is below Hubble’s detection limit. The dust cloud is estimated to have expanded by now to a size larger than the orbit of Earth around the sun.

Equally confounding is that the team reports that the object is more likely on an escape path, rather than on an elliptical orbit, as expected for planets. This is based on the researchers adding later observations to the trajectory plots from earlier data.

“A recently created massive dust cloud, experiencing considerable radiative forces from the central star Fomalhaut, would be placed on such a trajectory,” Gáspár says. “Our model is naturally able to explain all independent observable parameters of the system: its expansion rate, its fading, and its trajectory.”

Because Fomalhaut b is presently inside a vast ring of icy debris encircling the star Fomalhaut, colliding bodies would likely be a mixture of ice and dust, like the comets that exist in the Kuiper belt on the outer fringe of our solar system. Gáspár and Rieke estimate that each of these comet-like bodies measured about 125 miles across, roughly half the size of the asteroid Vesta.

The authors say their model explains all the observed characteristics of Fomalhaut b. Sophisticated modeling of how dust moves over time, done on a cluster of computers at the university, shows that such a model is able to fit quantitatively all the observations. According to the authors’ calculations, the Fomalhaut system, located about 25 light-years from Earth, may experience one of these events only every 200,000 years.

Gáspár and Rieke—along with other team members—will also be observing the Fomalhaut system with NASA’s upcoming James Webb Space Telescope in its first year of science operations. The team will be directly imaging the inner warm regions of the system, and for the first time in a star system other than our own, they will obtain detailed information about the architecture of Fomalhaut’s elusive asteroid belt. The team will also search for bona fide planets orbiting Fomalhaut that might still await discovery.

Their paper appears in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The Hubble Space Telescope is a project of international cooperation between NASA and the European Space Agency. NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, manages the telescope. The Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland, conducts Hubble science operations. STScI is operated for NASA by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy in Washington, DC.

Source: University of Arizona