Researchers have the first validation of a new program to assess the risk of seizures in patients with epilepsy.

In a preliminary study, the Epilepsy Seizure Assessment Tool (EpiSAT) proved equally able or better than 24 specialized epilepsy clinicians at using patients’ histories to identify periods of heightened propensity for seizures.

“Epilepsy affects more than 3.4 million people nationwide,” says coauthor Marina Vannucci, professor of statistics at Rice University. “This study could serve as a benchmark case for other diseases or situations that could employ a statistical approach.”

Epilepsy seizure counting

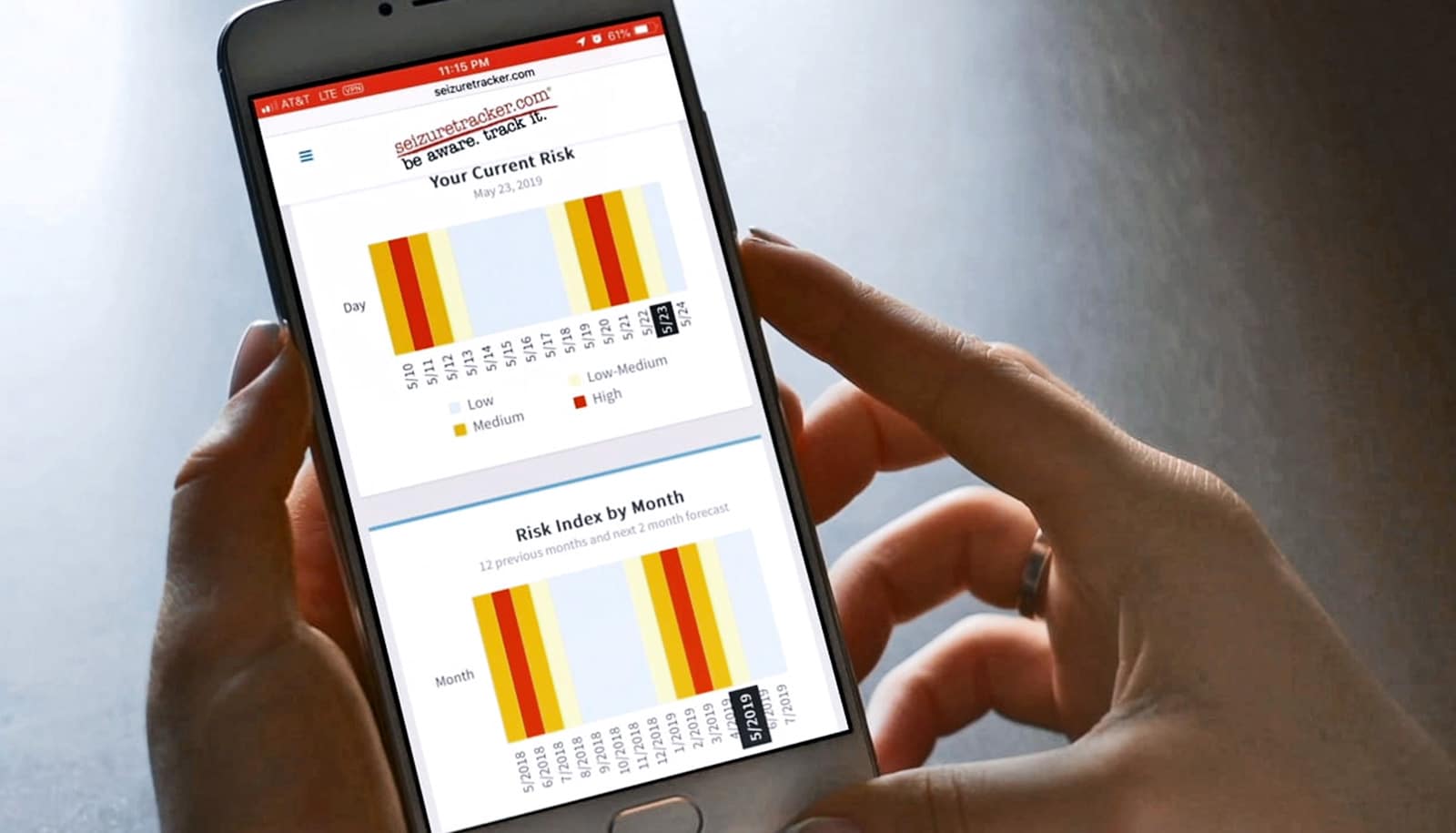

The researchers’ automated machine-learning algorithm correctly identified changes in seizure risk—improvement, worsening, or no change—in more than 87% of cases. They achieved those results by analyzing 120 seizures from four “synthetic” diaries and 120 seizures from real seizure diaries that SeizureTracker.com, one of the largest electronic seizure diaries in the world, gathered. EpiSAT showed “substantial observed agreement” with clinicians more than 75% of the time, according to the findings, which appear in Epilepsia.

“One challenge in treating people with epilepsy is that, like the chance of rain, there has never been a good way to quantify seizure risk and to determine whether apparent changes in seizure frequency reflect chance or actual improvement or worsening in their clinical state,” says Vikram Rao, chief of the epilepsy division and an associate professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco. “The algorithm that Dr. Chiang developed in this study directly addresses that clinical dilemma.”

Clinicians rely on patient seizure diaries to get a sense of the severity and frequency of the attacks.

“Seizure counting is one of the oldest indices physicians rely on to monitor the underlying epilepsy burden and assess response to treatment,” says lead author Sharon Chiang, now a resident physician at the UC San Francisco neurology department.

“A fundamental challenge is that changes in observed seizure frequency are not necessarily reflective of treatment, but may be due to natural variability. Crude estimates of seizure frequency can be misleading, and if misinterpreted as a change in seizure propensity can lead to unnecessary or harmful treatment decisions,” she says.

Mimicking reality

Matching real patient data to simulated data allowed the team to know with certainty when the algorithm was on target and raised confidence in their ability to analyze patient data, Vannucci says.

“The ability to mimic what happens in reality lets us assess the performance of our method,” she says. “We can know for sure whether it recovers the truth.”

“This new publication shows the benefits of a quantitative approach that can guide treatment when deciding whether treatment has been helpful,” says John Stern, a professor of neurology and co-director of the Seizure Disorder Center at the University of California, Los Angeles, as well as co-principal investigator of the study.

The study follows extensive collaboration by the same team of researchers. A 2017 outlined a method integrating neuroimaging scans to identify patients at high risk of continued seizures before employing invasive surgery that may or may not provide complete relief.

Vannucci says the team plans to incorporate data from electronic health records to refine EpiSAT. “Including possible covariates could serve as an additional validation of the method.” The ultimate goal is to see the tool deployed in clinical practice.”

Additional coauthors are from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Seizure Tracker LLC, Baylor University, the National Institutes of Health, and UC San Francisco. The National Institutes of Health and National Science Foundation supported the research.

Source: Rice University