A new book describes how millions of enslaved people were kept in what was effectively a continuing bondage after emancipation.

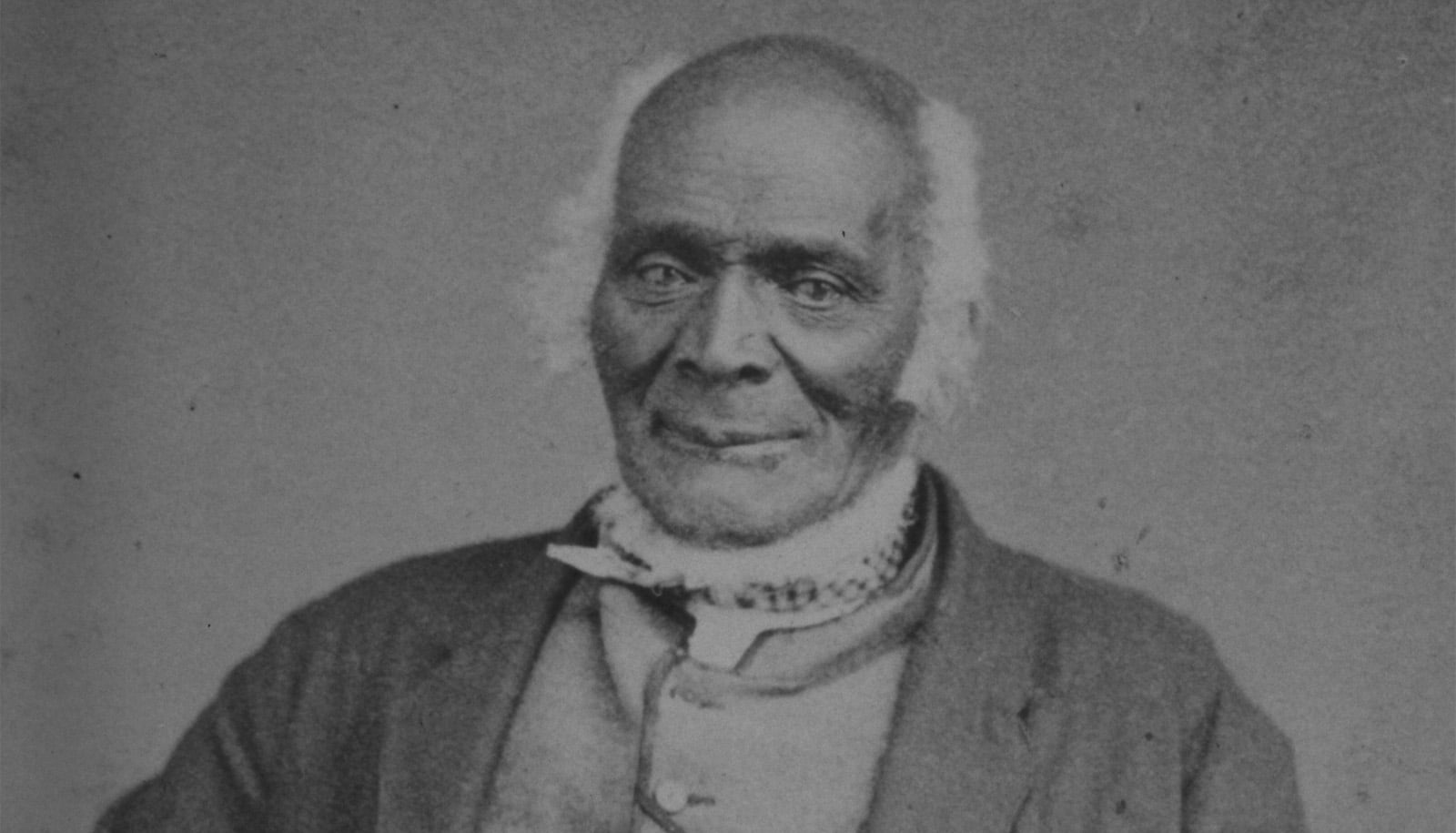

In 1790—six years after the state of Connecticut officially abolished slavery—James Mars was born there to a Black family that had been enslaved in the state. The law gave the former owner of the family the right to keep the newborn child enslaved until he was 25, even though his parents were freed.

That man planned to take Mars and his brother as youngsters to the South, to be sold into permanent slavery, but the family escaped with him. Later captured, he was forced to work in the man’s house and fields, and was sold at age 15 to another Connecticut slave owner—all sanctioned by the state’s emancipation law.

Mars’ story is emblematic of the entire process of emancipation from slavery in the US, from New England to the deep South, and across the world, says Kris Manjapra, a professor of history at Tufts University.

“I call the silencing of the historical experiences of people who are subordinated by the racial caste system ‘ghostlining.'”

His new book, Black Ghost of Empire: The Long Death of Slavery and the Failure of Emancipation (Scribner, 2022), details a history that is often glossed over. It describes how millions of enslaved people were not accorded their rights as full members of society for more than a century.

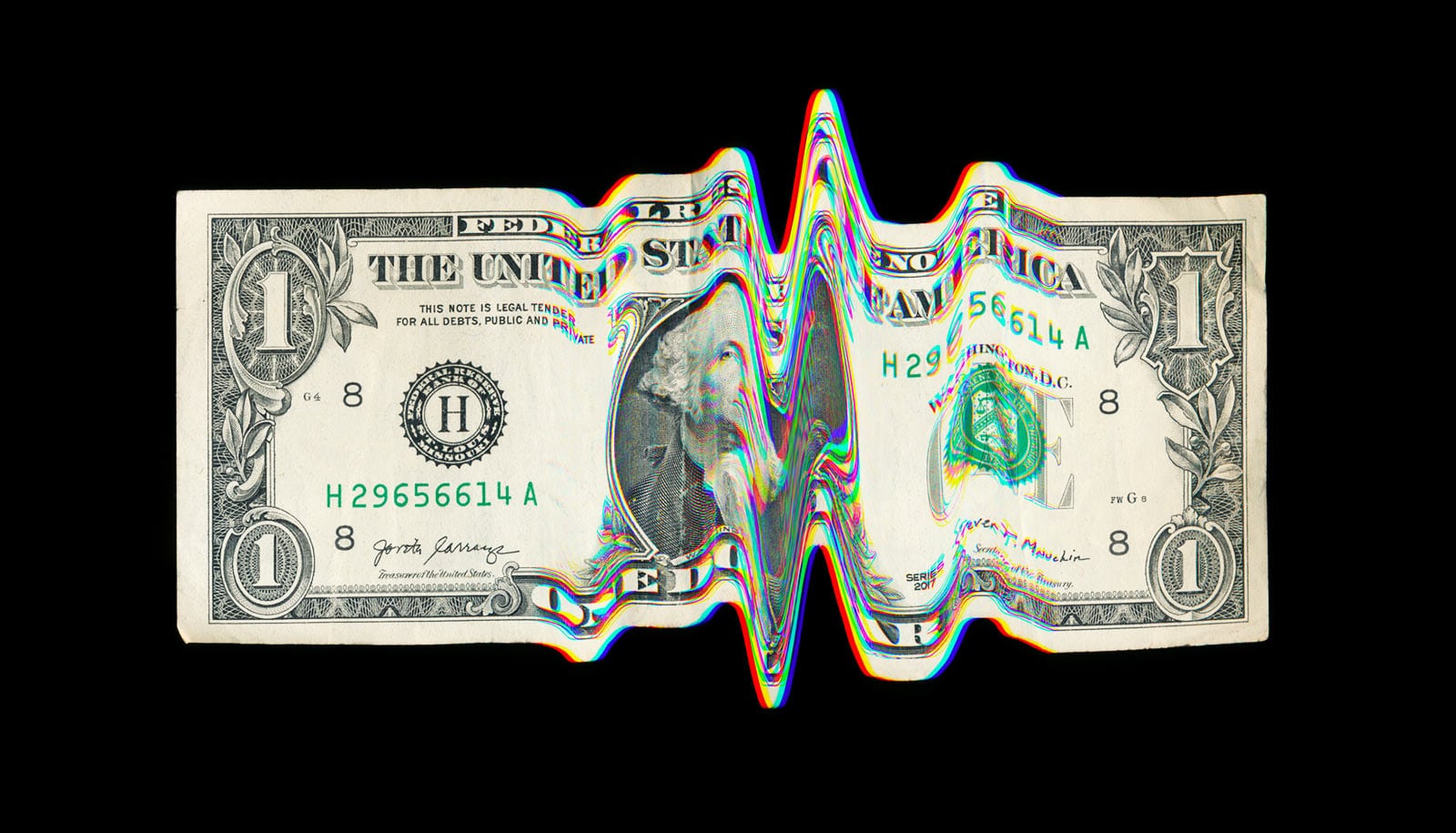

Even as formerly enslaved people of African descent in the Americas were nominally freed, they did not receive compensation for their past labor or the abuse they had suffered. Instead, it was the enslavers who were paid, often princely sums, as governments chose to compensate them for the loss of their “property.”

“In 2018, I discovered that Britain had taken 180 years to pay off the national debt it generated, beginning in 1833, to pay reparations to enslavers during the British empire’s emancipation process,” Manjapra says. “I knew then that I had to write a book to understand the transnational significance of this discovery.”

Indeed, as he writes in the book, in 2018 the British Treasury congratulated itself for having spent £20 million in stock and bonds in the 1830s “to buy the freedom for all slaves in the Empire,” it tweeted. That debt was not paid off until 2015. In today’s dollars, that’s more than $200 billion paid to enslavers and their descendants.

And the enslaved? They didn’t see a penny of that money. They had to keep working for free for five years after being “freed” under the law, and ended up with nothing, essentially forced into poverty. “The British state never repudiated the slave-owner reparations, just as it has never apologized for the centuries of slavery that it sanctioned and promoted,” Manjapra writes. The same happened in many other countries as well.

Emancipation vs. liberation

The US was just one piece of a larger system that exploited and harmed people of African descent. “The national wealth of many settler nations in North and South America, as well as countries across Western Europe, was built on slavery’s plunder,” Manjapra says. The money flowing from lucrative European sugar plantations in the Americas, for example, helped fund the Industrial Revolution.

Slavery had been part of the landscape of North America since the beginning of the colonies, more so than is commonly remembered. For instance, enslaved people made up almost 20% of New York’s population by the 1740s—second only to Charleston, South Carolina, in percentage terms.

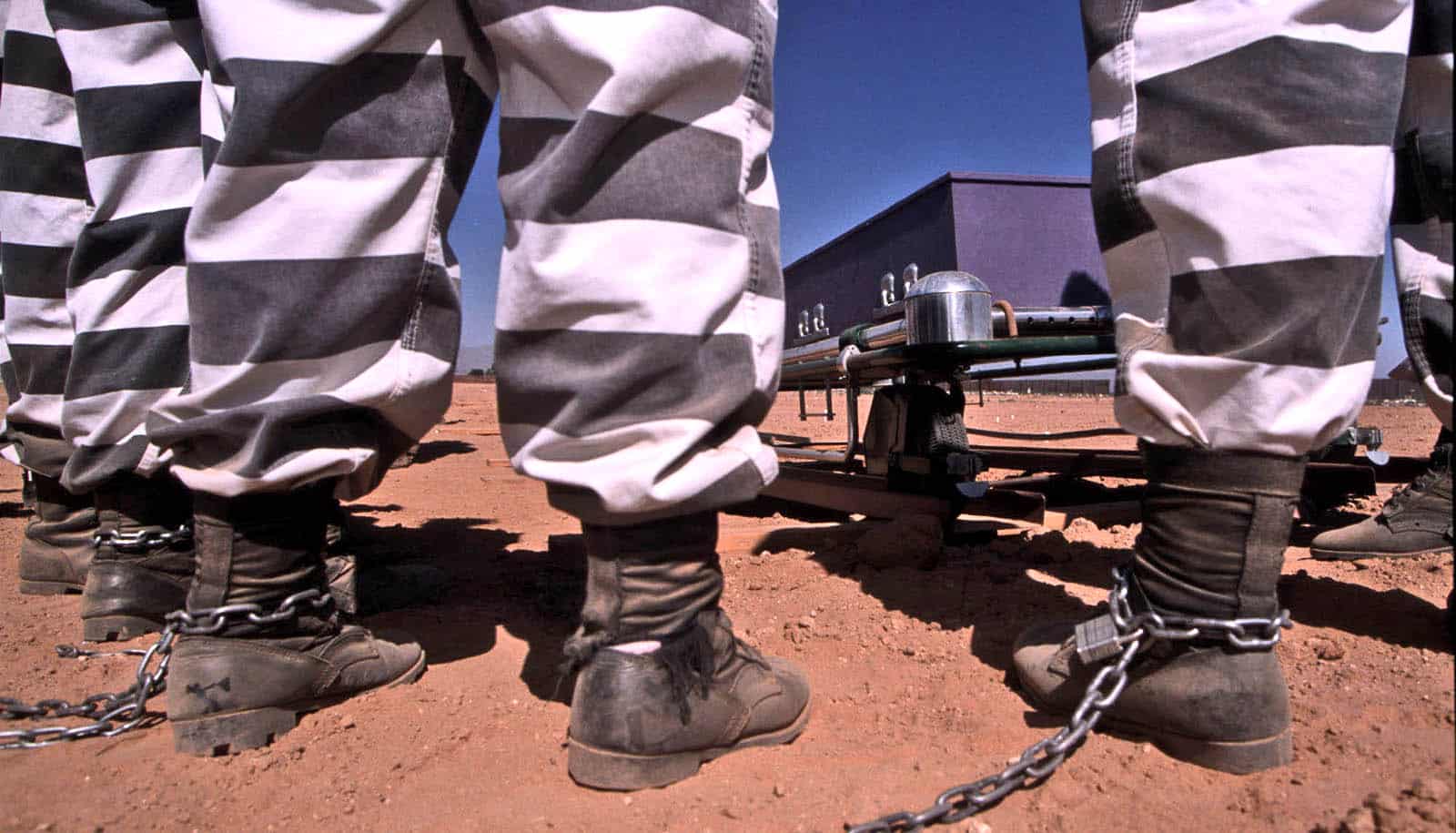

Having grown for centuries, slavery did not end quickly. In his book, Manjapra details the slow and halting process of abolition across North America, the Caribbean, and Latin America. “How slavery ended, not just that it ended, should matter to us,” he says.

Take New York’s emancipation act. Just as with Connecticut’s abolition of slavery, New York’s was guaranteed to delay freedom. The state’s 1817 statute promised to free all slaves born before 1799—but not until 1827, Manjapra notes, protecting enslaver’s businesses and lifestyles above the interests of the enslaved.

Emancipation has always been a top-down process, enacted by those in power. “Emancipations always happened on the terms of the enslavers,” says Manjapra. “I’d say that it was liberation, not emancipation, that Black communities always fought for,” he says. “Liberation takes place on the terms and according to the needs of the enslaved and their descendants.”

After the Civil War, “America’s emancipation marked not a jubilee date to end slavery,” he writes, “but an ongoing and expanding dirty war against Black communities.” Across the North, post-slavery laws and policies “excluded Black communities from full participation in society,” he says, while Jim Crow laws, which sought to subjugate the formerly enslaved, swept the country, especially the Southern states.

After the Haitian revolution

Manjapra tells the story of Haiti, where hundreds of thousands of enslaved Africans were forced to work under brutal conditions in sugar plantations, making French owners tremendously wealthy. By the 1770s, the territory was accounting for more than a quarter of all French national revenue. But in the early 1800s, the workers rose up against their enslavers, achieving independence from France.

France battled against the newly independent Haiti, forcing payment of reparations to the French slave owners. Those payments began in 1825 and continued for 120 years, sometimes taking up as much as 80% of Haiti’s revenues to pay former slaveowners.

As one British abolitionist wrote in the 1820s, as quoted by Manjapra: “Shall robbers, or withholders of their fellow creatures’ liberty be not only exempt from punishment, but entitled to compensation for the relinquishment of their human prey?”

The answer was clearly yes, as the people writing the emancipation laws and their compensation clauses were often the same enslavers who stood to benefit financially.

But as in Haiti, there are examples of enslaved people of African descent rising up to break their shackles. Across the Caribbean, enslaved people escaped their confinement, creating their own sheltered communities.

“I always find the free villages that emerged in the 1830s and 1840s across the Caribbean as an inspiring example of what liberation meant for the freed people,” Manjapra says. “In these villages, people owned land in common, they farmed to feed their families and to sell their goods on the market, and they practiced their cultural ways, with roots in Africa and in Indigenous Caribbean traditions.”

‘Ghostlining’ and repair

According to Manjapra, it’s impossible to study emancipations, “which were designed to deny repair to the enslaved and their descendants,” without also studying reparations.

Reparations are about “the ongoing struggle to obtain apology and amends, and the satisfaction of restitution and redress for the generational harm caused by slavery and its continuities.”

For him, reparations are not fundamentally about payments to individuals, but about “the search to re-create social reciprocities that hundreds of years of bondage, emancipation, racist property rights, and imperial myths have destroyed.”

That involves changing laws and policies, and redistributing wealth, privilege, and social benefits. “Reparative justice creates the scope for reciprocity and trust to grow anew, and this benefits everyone involved,” he says.

The call for reparations to redress centuries of harm that enslaved African peoples suffered is mostly ignored in America and Europe, and Manjapra isn’t surprised. “We are still awaiting a proper reckoning by national governments and international entities, such as the United Nations, with this history,” he says.

“I think US society is still organized by a racial caste system that assigns status, privilege, benefits, entitlements, and property relations according to ideas of racial difference and hierarchy,” he says.

“This system also governs the way history and collective experience is represented; it governs what gets talked about and what gets silenced,” he says. “I call the silencing of the historical experiences of people who are subordinated by the racial caste system ‘ghostlining.'”

But there is a way to overcome this ghostlining, Manjapra says, through activism in writing, scholarship, art, and cultural production. His book is one example of this effort, which he calls “an essential dimension in the struggle against the racial oppression.”

Source: Taylor McNeil for Tufts University