A new graphene-based electronic tattoo that attaches to the palm can sense if you’re feeling stressed out.

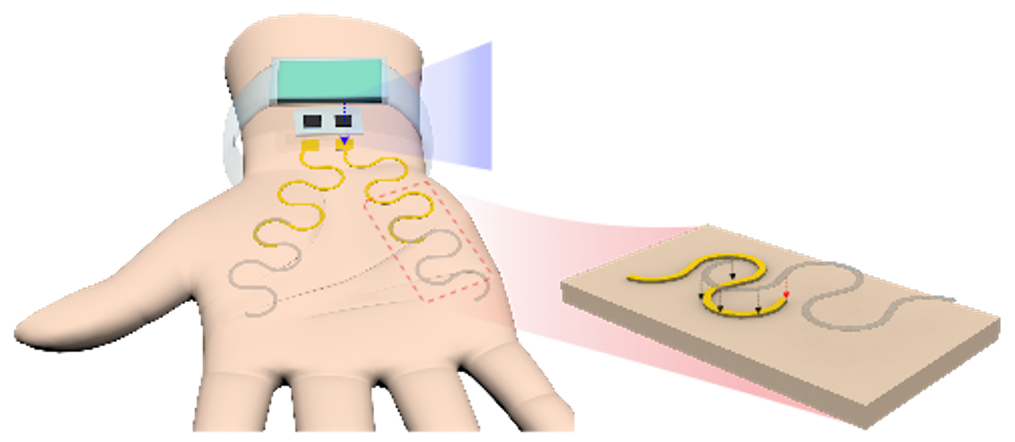

It’s nearly invisible and connects to a smart watch.

Our palms tell us a lot about our emotional state, tending to get wet when people are excited or nervous. This reaction is used to measure emotional stress and help people with mental health issues, but the devices to do it now are bulky, unreliable, and can perpetuate social stigma by sticking very visible sensors on prominent parts of the body.

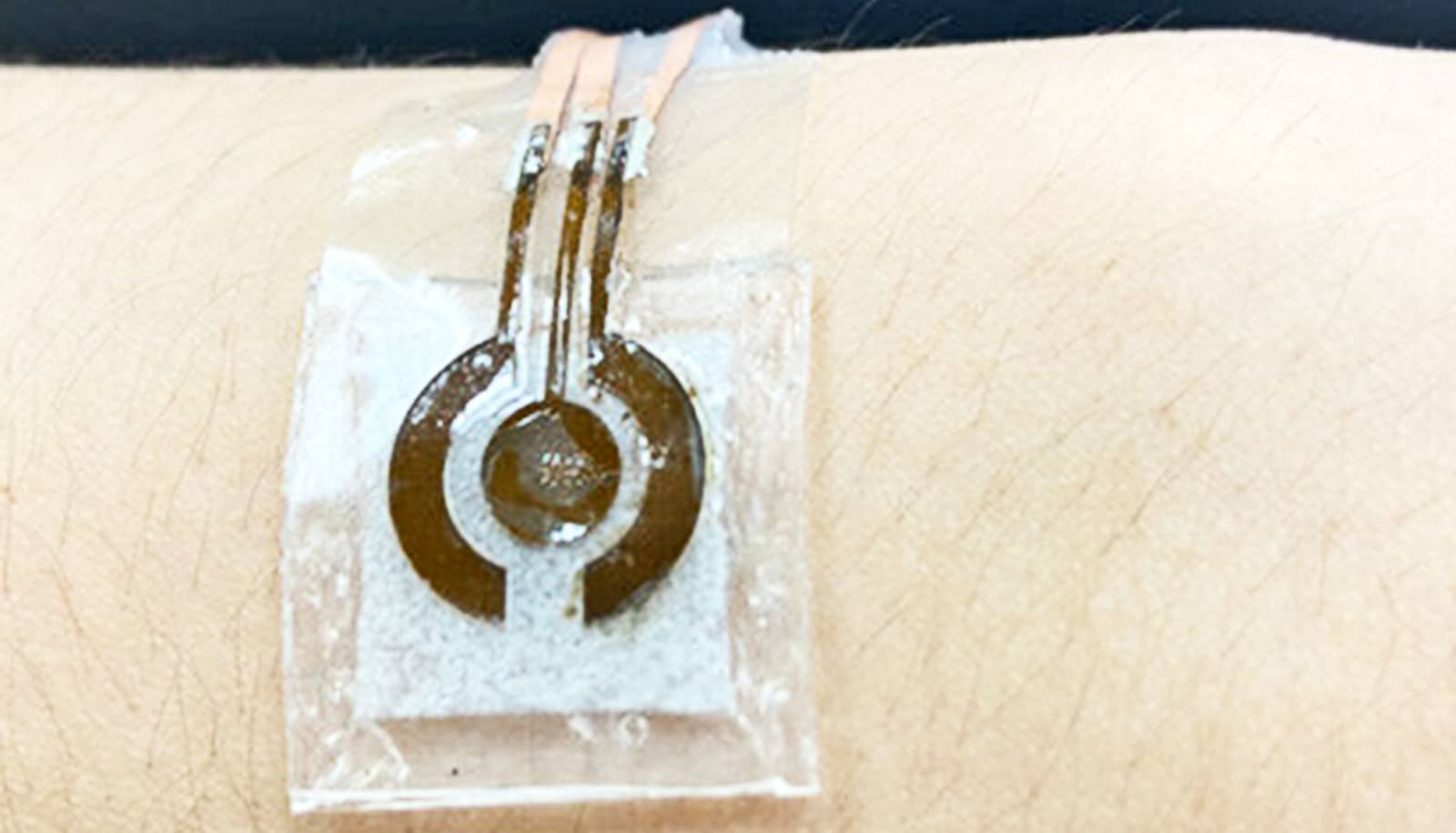

As reported in Nature Communications, the researchers applied emerging electronic tattoo (e-tattoo) technology to this type of monitoring, known as electrodermal activity or EDA sensing.

“It’s so unobstructive that people sometimes forget they had them on, and it also reduces the social stigma of wearing these devices in such prominent places on the body,” says lead author Nanshu Lu, professor in the aerospace engineering and engineering mechanics department at the University of Texas at Austin.

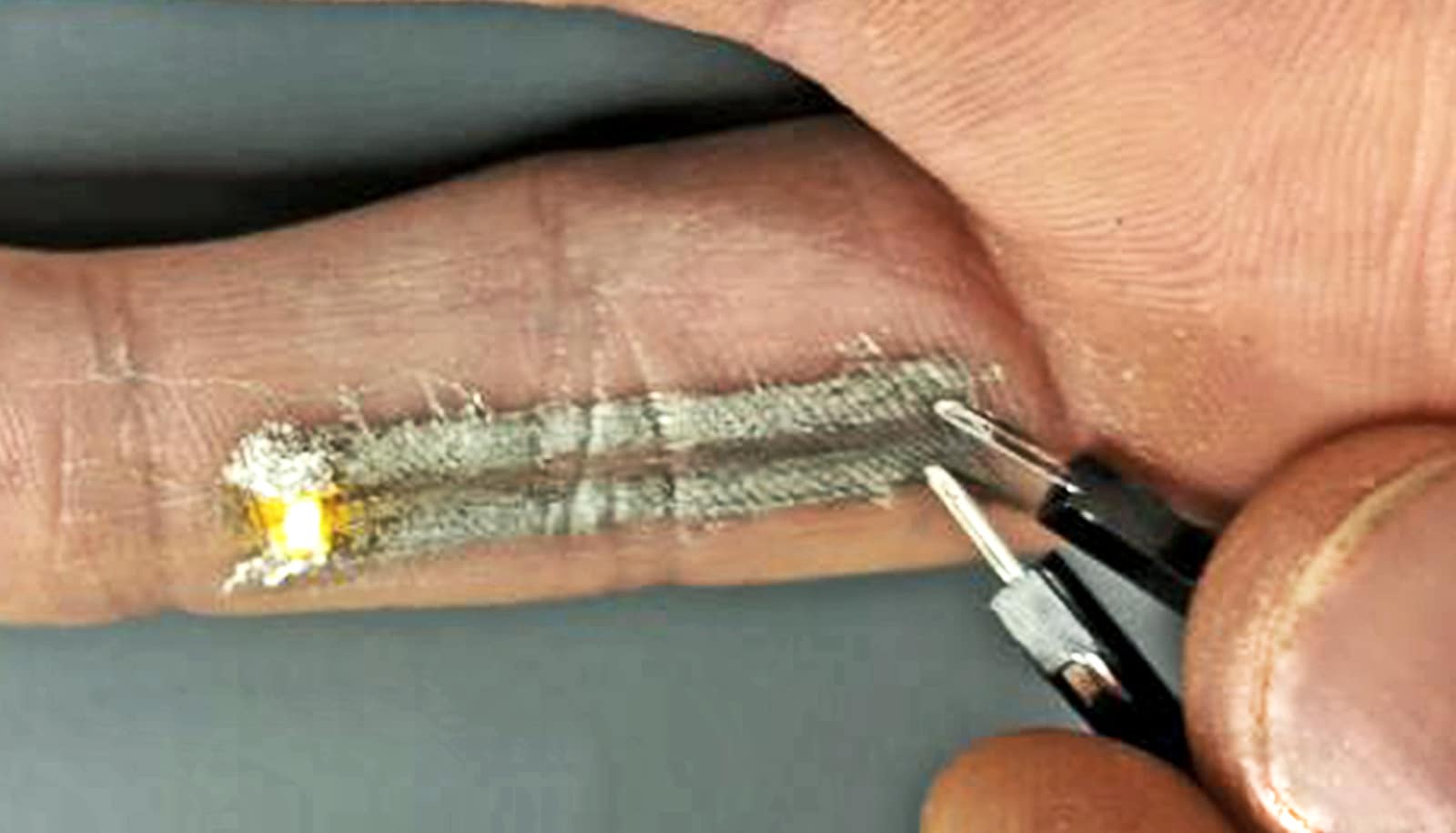

Lu and her collaborators have been advancing wearable e-tattoo technology for many years. Graphene has been a favorite material because of how thin it is and how well it measures electrical potential from human body, leading to very accurate readings.

But, such ultra-thin materials can’t handle much, if any strain. So that makes applying them to parts of the body that include a lot of movement, such as the palm/wrist, challenging.

The secret sauce of this discovery is how the e-tattoo on the palm is able to successfully transfer data to a rigid circuit—in this case a commercially available smart watch, in out-of-lab, ambulatory settings. The researchers used a serpentine ribbon that has two layers of graphene and gold partially overlapped.

By snaking the ribbon back and forth, it can handle the strain that comes with movements of the hand for everyday activities like holding the steering wheel while driving, opening doors, running, etc.

Current palm monitoring tech uses bulky electrodes that fall off and are very visible, or EDA sensors applied to other parts of the body, which gives a less accurate reading.

Other researchers have tried similar methods using nanometer-thick straight-line ribbons to connect the tattoo to a reader, but they couldn’t handle the strain of constant movement.

The researchers were inspired by virtual reality (VR), gaming and the incoming metaverse for this research, Lu says. VR is used in some cases to treat mental illness; however, the human-aware capability in VR remains lacking in many ways.

“You want to know whether people are responding to this treatment,” Lu says. “Is it helping them? Right now, that’s hard to tell.”

Additional coauthors are from Texas A&M University and UT Austin.

Source: University of Texas at Austin