Walls, furniture, steering wheels, toys, and even Jell-O can become touch sensors with a new technology called Electrick.

Touch sensing is most common on small, flat surfaces such as smartphone or tablet screens. Researchers have found a way, however, to turn surfaces of a wide variety of shapes and sizes into touchpads using tools as simple as a can of spray paint.

The “trick” is to apply electrically conductive coatings or materials to objects or surfaces or to craft objects using conductive materials. By attaching a series of electrodes to the conductive materials, researchers showed they could use a well-known technique called electric field tomography to sense the position of a finger touch.

“For the first time, we’ve been able to take a can of spray paint and put a touch screen on almost anything,” says Chris Harrison, assistant professor in the Human-Computer Interaction Institute (HCII) at Carnegie Mellon University and head of the Future Interfaces Group.

Until now, large touch surfaces have been expensive and irregularly shaped or flexible touch surfaces have been largely available only in research labs. Some methods have relied on computer vision, which can be disrupted if a camera’s view of a surface is blocked. The presence of cameras also raises privacy concerns.

With Electrick, conductive touch surfaces can be created by applying conductive paints, bulk plastics, or carbon-loaded films, such as Desco’s Velostat, among other materials.

Yang Zhang, a PhD student in HCII, says Electrick is both accessible to hobbyists and compatible with common manufacturing methods, such as spray coating, vacuum forming, and casting/molding, as well as 3D printing.

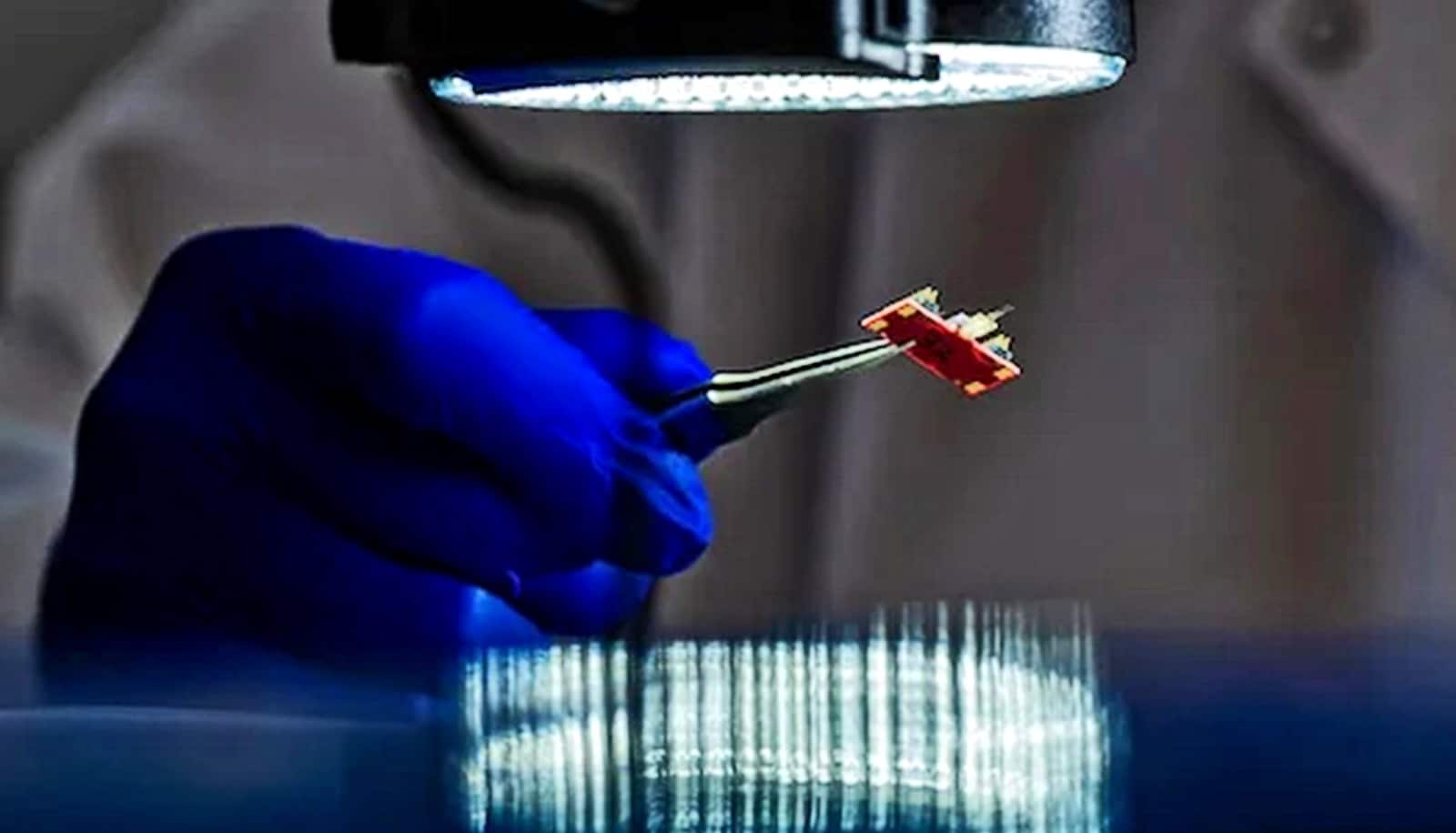

These 3D-printed electrodes for screens are transparent

Like many touchscreens, Electrick relies on the shunting effect—when a finger touches the touchpad, it shunts a bit of electric current to ground. By attaching multiple electrodes to the periphery of an object or conductive coating, Zhang and his colleagues showed they could localize where and when such shunting occurs.

They did this by using electric field tomography—sequentially running small amounts of current through the electrodes in pairs and noting any voltage differences.

The tradeoff, in comparison to other touch input devices, is accuracy. Even so, Electrick can detect the location of a finger touch to an accuracy of one centimeter, which is sufficient for using the touch surface as a button, slider, or other control, Zhang says.

Zhang, Harrison, and fellow PhD student Gierad Laput used Electrick to add touch sensing to surfaces as large as a 4-by-8-foot sheet of drywall, as well as objects as varied as a steering wheel, the surface of a guitar, and a Jell-O mold of a brain. Even Play-Doh can be made interactive with Electrick.

They used the technology to make an interactive smartphone case—opening applications such as a camera based on how the user holds the phone—and a game controller that can change the position and combinations of buttons and sliders based on the game being played or the player’s preferences.

Zhang says the Electrick surfaces proved durable. Adding a protective coating atop the conductive paints and sheeting also is possible.

The David and Lucile Packard Foundation supported this research. The group will present a paper on Electrick at the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, this week in Denver, Colorado.

Source: Carnegie Mellon University