New research clarifies how female reproductive cells—eggs or oocytes—get the food they need to grow and remain fertile.

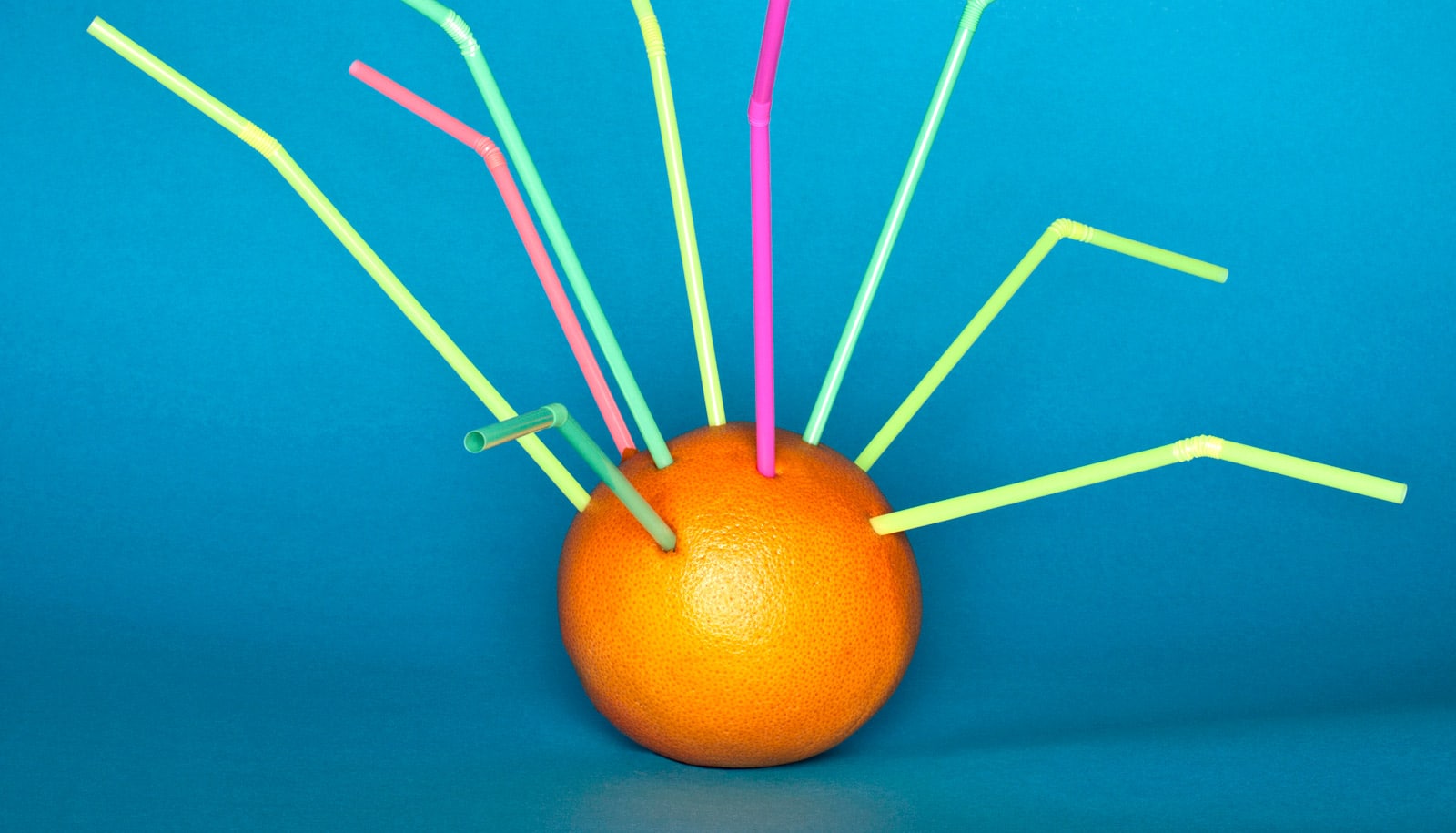

The egg gets its food from little arm-like feeding tubes (called filopodia) that jut out from tiny cells surrounding the egg and must poke through a thick wall coating the egg in order to feed it. Until recently, scientists did not really understand the place and timing of the feeding tubes’ construction.

It turns out the egg is in charge and its communication skills are highly sophisticated. When it’s time to get food, the egg sends signals to the tiny surrounding cells to make the feeding tubes, and as it grows and needs more nourishment, it signals them to make even more tubes.

These findings, which push the scope of our understanding of female fertility, appear in Current Biology.

The study, conducted in mice, reveals that growth factors—especially one known as growth differentiation factor 9—coming from the eggs drove the feeding tube multiplication and growth process, acting directly upon the genetic machinery of the follicle cells surrounding the egg. These discoveries put the spotlight directly on the egg itself, says Hugh Clarke, who led the research team at the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre.

“It shows that the egg is playing an active role in creating the microenvironment that it needs to continue its development,” says Clarke, lead study author, who is also a senior scientist from the Child Health and Human Development Program at the RI-MUHC and a professor and research director of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at McGill University.

“We observed that the whole process of egg development and its interaction with its environment is not static. It’s very dynamic,” adds first study author Stephany El-Hayek, who was a PhD student in Clarke’s lab at the time of the work.

7 tips for avoiding chemicals that harm fertility

The team also found that in older mice, the cells surrounding the egg produced fewer feeding tubes. Scientists know that the eggs of older women are less successful in producing healthy babies, but they don’t know the reason why. Clarke’s research offers a new possible explanation.

Might it be because the cells surrounding the egg are not good at making enough feeding tubes as the egg grows older? The answer to that question, which Clarke’s team is now investigating, could one day lead to the possibility of increasing fertility or even retaining fertility longer into older age, he says.

“Understanding how the egg interacts with its environment will allow us to ensure that growing eggs retain their fertility,” says Clarke. “But it could also lead to developing techniques to grow healthy eggs in the laboratory in an effort to preserve fertility in women who have cancer,” says Clarke.

Source: McGill University