New research identifies the pathway by which the body’s natural process for removing dead and dying cells can actually fuel tumor growth, a little understood paradox of certain cancers.

The finding could help researchers develop drugs to block the harmful tumor acceleration, while still allowing the body to clear out the dying cells, says study lead author Hernan Roca, associate research scientist at the University of Michigan School of Dentistry.

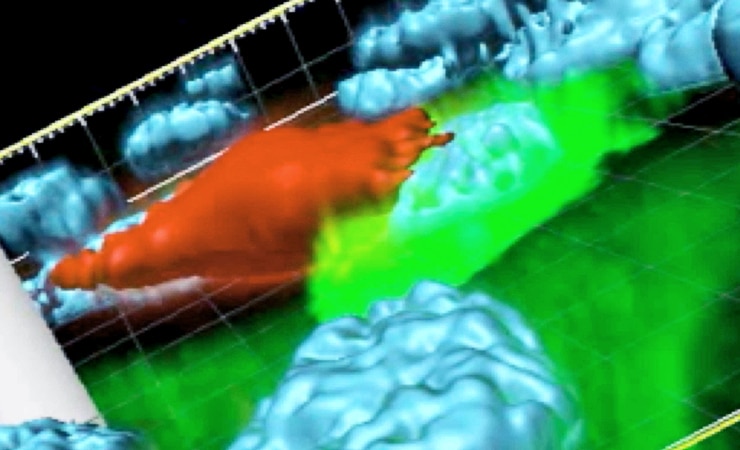

This process of removing cellular debris is called efferocytosis, and it’s a critical and normal function in both healthy people and those with cancer. These cellular house cleaners are called phagocytes, also known to be the first immune system responders to resolve infections by foreign invading organisms.

The study found that with metastatic prostate cancer cells, efferocytosis produced a pro-inflammatory protein called CXCL5 that isn’t normally released during cellular cleanup in healthy situations. Researchers found this CXCL5 protein stimulated tumor growth.

When researchers induced cell death in mouse bone tumors, it correlated with an increase of CXCL5, and the growth of tumors with induced cell death accelerated. Blocking the CXCL5 protein in mice, however, hindered tumor progression.

Next, researchers took these findings to look at blood samples from human patients with metastatic prostate cancer, and found that their level of inflammatory CXCL5 was higher relative to localized prostate cancer patients, or healthy patients.

‘Pac-Man’ protein tells cells to eat sickly neighbors

“In the presence of cancer, uncontrolled cell growth is also accompanied by a high, or significant, amount of cancer cell death,” and those dead cells must be removed, Roca says. “The challenge for the future is to understand how to treat these patients to avoid this pro-inflammatory and tumor promoting response, while still preserving the essential function of cell removal.”

When prostate cancer metastasizes it frequently appears in bone, and at that point it’s incurable. Since bone is a rich reservoir of these phagocytic immune cells, these findings shed light into novel effective cancer therapies.

The researchers report their findings in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Source: University of Michigan