Researchers may have found why our skin can become itchy and inflamed due to conditions like eczema, also known as atopic dermatitis.

A common bacterium called Staphylococcus aureus sometimes stimulates production of a protein that causes our own cells to react and cause the inflammation, the researchers report.

“Our skin is covered with bacteria as part of our normal skin microbiome and typically serves as a barrier that protects us from infection and inflammation,” says Lloyd Miller, associate professor of dermatology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “However, when that barrier is broken, the increased exposure to certain bacteria really causes problems.”

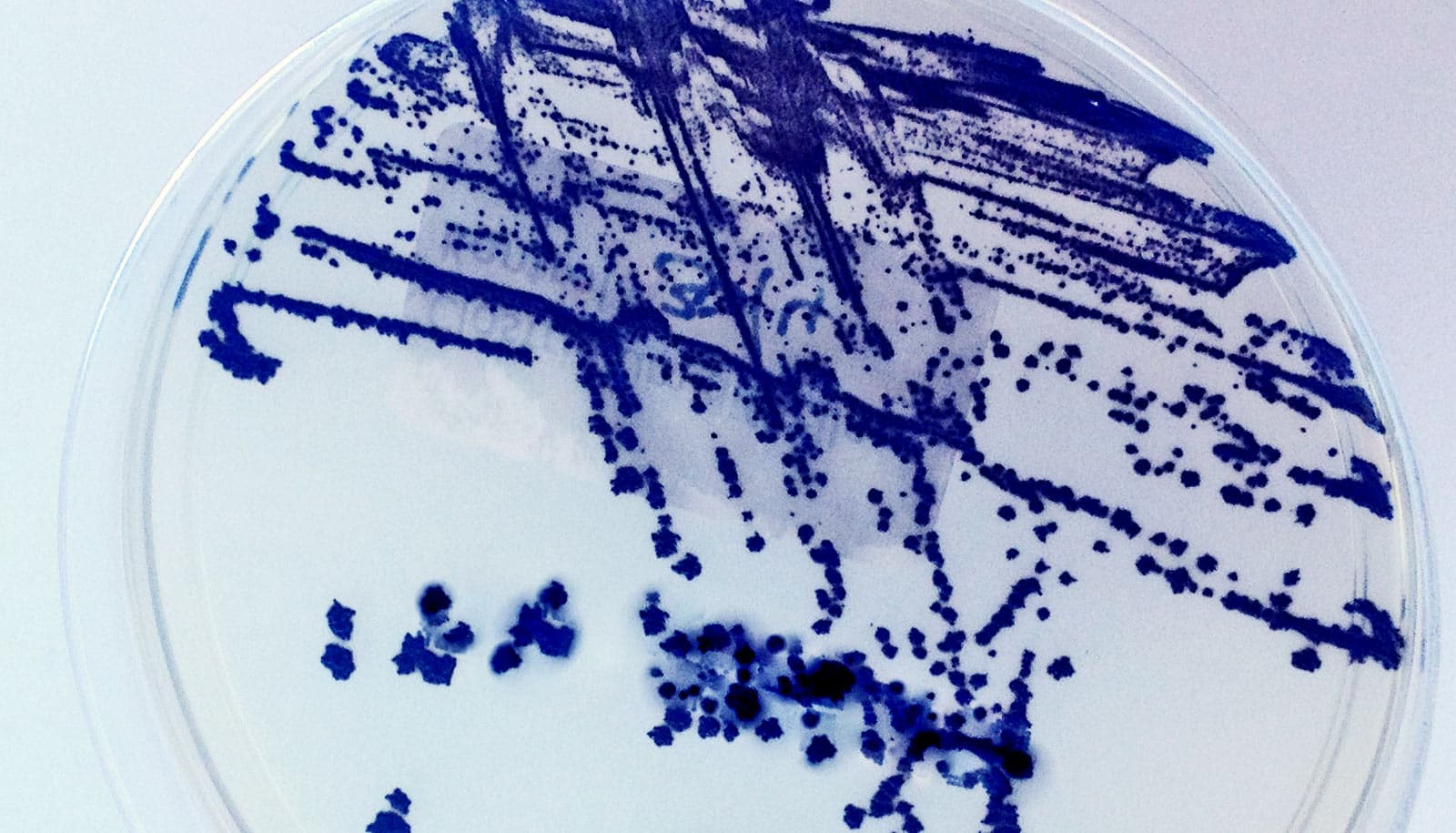

S. aureus is an important human pathogen, already known as the most common cause of skin infections in people. In the United States, 20 to 30 percent of the population has it living on the skin or in the nose, Miller adds, and over time, up to 85 percent of people come into contact with it.

Eczema is an inflammatory skin disease that affects 20 percent of children and about 5 percent of adults. Ninety percent of patients with eczema have exceedingly high numbers of S. aureus bacteria on their inflamed skin.

Untreated eczema can lead to other allergic conditions, including asthma, food allergies, seasonal allergies, and conjunctivitis. Blocking the skin inflammation in eczema has the potential to prevent these unwanted conditions.

“We don’t really know what causes atopic dermatitis, and there aren’t many good treatments for it,” Miller says.

Eczema not linked to heart disease risk after all

His team set out to learn more about how the condition arises, hoping that the work will lead to new treatments.

Previous research had shown that a rare disease that causes the skin to erupt into pustules begins with a genetic mutation that leads to unrestrained activity of a protein normally produced in our skin.

This, Miller says, was a clue that this same protein might have something to do with how bacteria on the skin’s surface induce inflammation.

The team tested this idea in mice by soaking small gauze pads with S. aureus and applying them to the back skin of both normal mice and mice they genetically engineered to lack a receptor for the suspect protein. Miller’s team found the normal mice developed scaly and inflamed skin, but the genetically engineered mice lacking protein activity had almost no skin inflammation.

“We are very excited about these results, as there is currently only a single biologic treatment targeting an inflammatory mechanism in atopic dermatitis on the market,” Miller says.

Antibiotics do little to ease kids’ eczema flare-ups

“As there are patients who don’t respond or have treatment failures, it would be better if there were biologics on the market that target alternative mechanisms involved in skin inflammation,” he says.

The researchers report their findings in a study in the journal Cell Host & Microbe.

Additional researchers who worked on the study are from Johns Hopkins, the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research at the US Food and Drug Administration, and Harvard University Medical School. The National Institutes of Health, the Atopic Dermatitis Research Network, and Pfizer Inc. funded the research.

Source: Archana Nilaweera for Johns Hopkins University