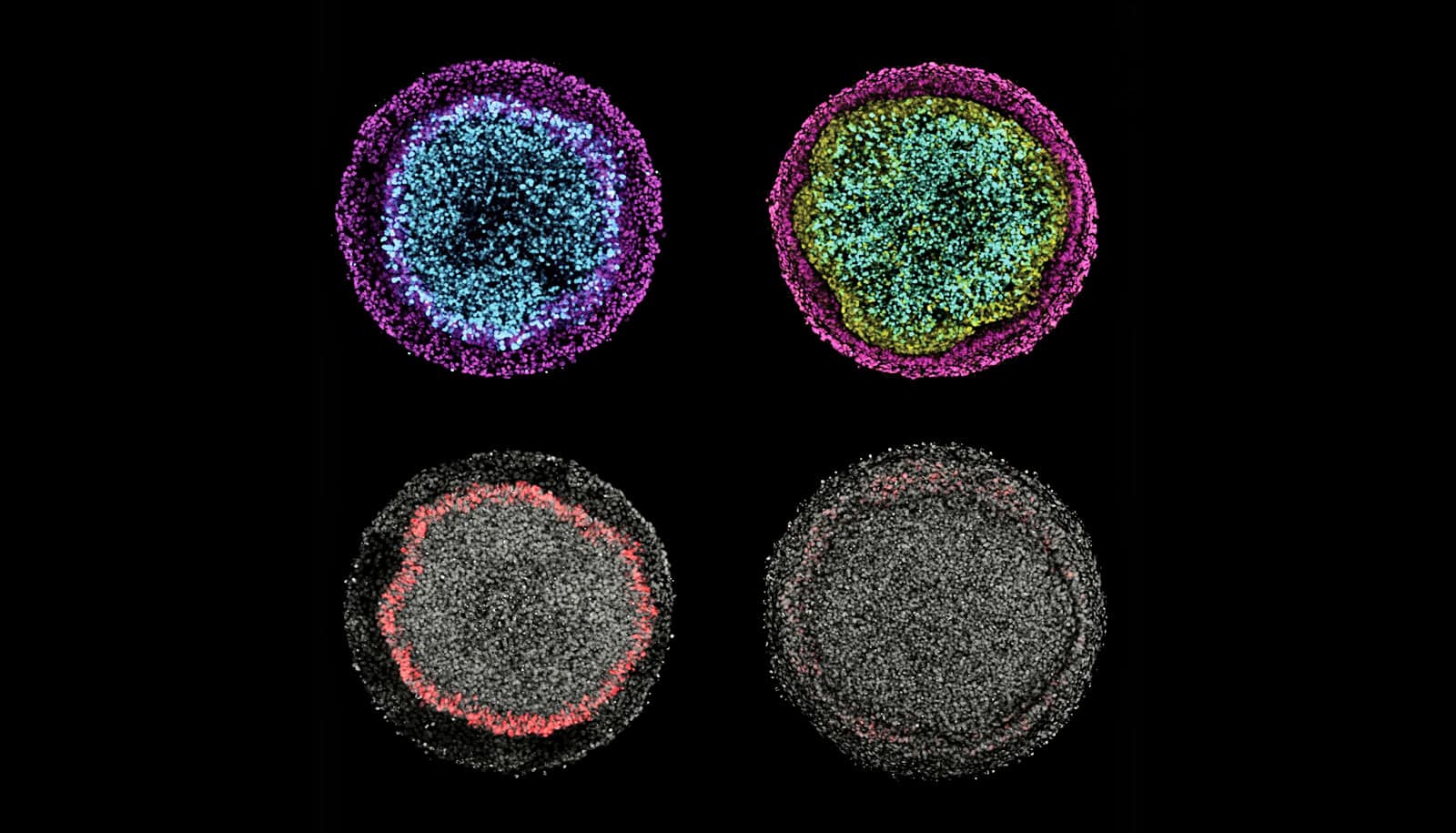

In a new system, all of the major cell types of ectoderm form in a culture dish in a pattern similar to that seen in embryos.

During embryonic development, the entire nervous system, the skin, and the sensory organs emerge from a single sheet of cells called the ectoderm. While there have been extensive studies of how this sheet forms all these derivatives, it hasn’t been possible to study the process in humans, until now.

The technique, based on controlling the geometry of stem cell colonies with microscale patterns, has helped them make the most comprehensive analysis yet of signaling pathways that drive patterning of human ectoderm.

“There are very few possible signals the embryo uses to generate the wide variety of cell types that arise,” says George Britton, graduate student at Rice University. “We want to understand the timing of these signals and how the cells interpret them in time to generate this variety.”

The study appears in Development, alongside an interview with the researchers.

Determined cells

The paper reveals that the balance between two signaling pathways, BMP and Wnt, is critical, and even a bit adaptable as they orchestrate patterning in the ectoderm. The logic they employ ultimately drives ectodermal cells to their fates, but the research showed they can take more than one road to get there.

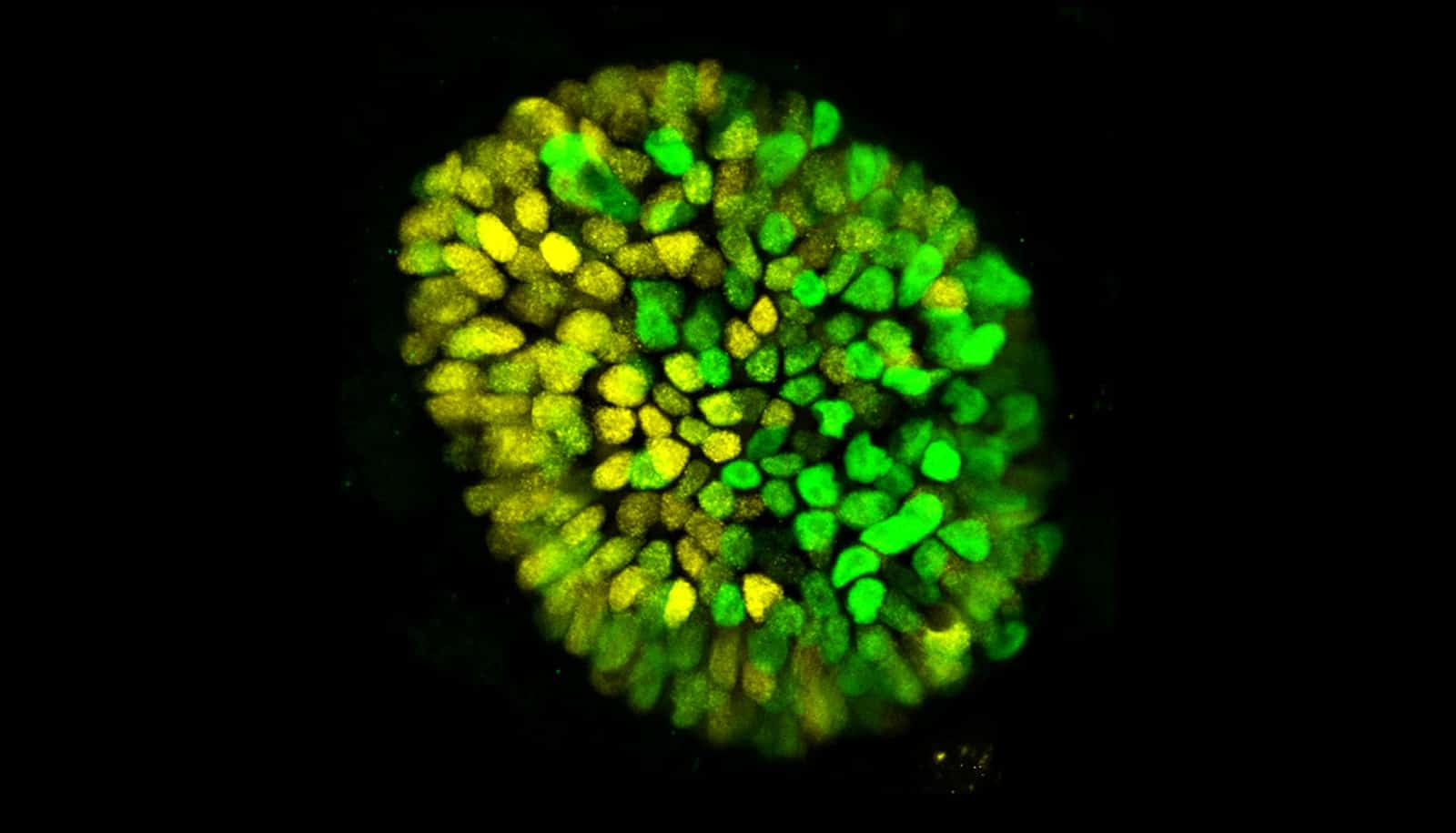

Britton says the micropatterned plates and a better understanding of how the signaling pathways work let them manipulate stem cell colonies to form unusual patterns at the start, but ultimately they always seemed to converge at the same place. “We found different trajectories of the signals that arrived at the same pattern,” he says.

That suggests the system by which stem cells become neurons, neural crest cells, neurogenic placodes, and epidermis cells is pretty robust.

“A lot of people are interested in the transcription factor network that directs neural crest emergence, so this is a powerful system to dissect the signals that contribute to that logic,” Britton says. “That was one thing we feel we contributed to the field.

“There’s also the idea that cells that have the ability to interpret relative levels of BMP and Wnt to incorporate the appropriate fate decision,” he says. “In the embryo, cells are moving around quite a bit in a space where signals and the ligands they’re exposed to are also moving around. It might be that cells are reading the relative levels to determine a certain fate.”

First days

The researchers observed that the relative activity of BMP and Wnt signaling determines cells’ decisions to become either neural crest or placodal cells, while BMP alone initiates and controls the size of the surface ectoderm, all within about the first four days.

“Four days is about right in the sense that cells are starting to make decisions: ‘I’m going to be a placodal cell, I’m going to be a neural crest cell, I’m going to [a] neural fate, and I’m going to an epidermal fate,” Britton says.

“We see that approximately a day or two after BMP treatment. But it’s hard to put a finger on whether these are the final patterns,” he says. “We’d have to do a more careful observation to make sure those placodal cells don’t change to neural crest cells, or vice versa. That will give us information on how these lineages and fates settle into a final pattern, maybe by day six or seven.”

Ectoderm ‘fates’

He says future studies will further refine their understanding of how signaling patterns work, as well as how the development of all the germ layers collaborate.

“Until now, studies of human stem cells differentiating to ectodermal fates were mostly about how to get all the cells in your culture dish to become a particular cell type; for example, how to make a dish full of neurons,” says Aryeh Warmflash, an assistant professor of biosciences and bioengineering.

“We are interested in a different question: How do cells interact with each other to make patterns of different cell fates? The system we developed does this outside the embryo and is allowing us to begin to tackle this question.”

The National Institutes of Health, through the National Institute of General Medical Sciences; the National Science Foundation, the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas, the University of Texas STARS program; and the Simons Foundation supported the research.

Source: Rice University