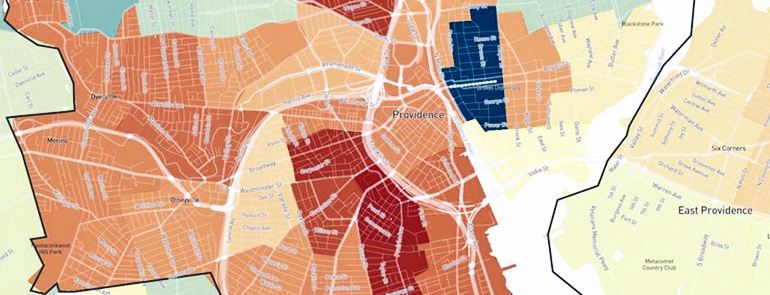

Researchers have created an interactive, map-based tool—the Opportunity Atlas—that can trace the root of people’s outcomes, such as poverty or incarceration, to the neighborhoods in which they grew up.

Social scientists have long understood that prospects for social and economic mobility among American adults are intimately linked to the neighborhoods in which they grew up.

The new research and interactive tool illustrate how growing up in one neighborhood compared to the next can make a vast difference in people’s lives.

Dream in decline

The researchers also launched a new research and policy institute, Opportunity Insights, to translate their findings into policy solutions that can improve the lives of Americans in communities across the country.

Their previous work showed that children’s chances of earning more than their parents did has declined from 90 percent to 50 percent in the last half century. The institute’s mission, the researchers say, is to use data to document the decline of the American dream, propose solutions to revive it, and empower families to rise out of poverty to achieve better life outcomes.

“Our approach is to partner with policymakers and others in communities nationwide, harnessing the power of big data to find local solutions for local problems,” says John Friedman, an economist at Brown University.

“Low rates of upward mobility in the United States are an incredibly challenging problem—but we can make progress by understanding exactly how opportunity is lacking in each specific setting and then tailoring the policy solution appropriately.”

To create the Opportunity Atlas, Friedman and colleagues studied anonymized data on 20 million Americans who are in their 30s today, measuring economic opportunity at the neighborhood level and identifying factors that impact average earnings, incarceration rates, and other outcomes by their parental income level, race, and gender.

The researchers began with a question: “Which neighborhoods in America offer children the best chances of climbing the income ladder?” Their work revealed six main findings about how neighborhoods shape the trajectories of those who grow up there:

Finding 1: Children’s outcomes in adulthood vary sharply across neighborhoods that are just a mile or two apart

That finding holds true even if children’s families have comparable incomes. In the Watts neighborhood in central Los Angeles, 44 percent of low-income black men were incarcerated on April 1, 2010, the day of the 2010 Census. By contrast, just 6.2 percent of black men who grew up in families with similar incomes in central Compton, 2.3 miles away, were incarcerated on that day.

Finding 2: Places that have good outcomes for one racial group do not always have good outcomes for others

To use the Watts example, Hispanic men who grew up in Watts have an incarceration rate of just 4 percent, compared to 44 percent for black men. Gender can also affect outcomes. Low-income black women who grow up in Watts earn three times as much, as adults, as low-income black men from that neighborhood. The researchers assert that policies addressing neighborhood issues should target specific subgroups rather than use a “one size fits all” approach.

Finding 3: Moving to a better neighborhood earlier in childhood can increase a child’s income by several thousand dollars

Children of low-income families who moved at the time of their birth from the Central District of Seattle, a low-upward-mobility area, to Shoreline, a high-upward-mobility area that is 10 miles north, earned $9,000 more per year at age 35 than those who moved in their 20s, according to the study.

Finding 4: Traditional indicators of local economic success such as job growth do not always translate into greater upward mobility

Cities like Atlanta and Charlotte that have high rates of job and wage growth also have among the lowest rates of upward mobility for children who grow up there, the researchers found. Those cities achieve high economic growth by attracting high-skilled outsiders to move there and fill high-paying jobs. Children are more likely to be upwardly mobile, the researchers write, if they grow up around people who have jobs.

Finding 5: Historical data on children’s outcomes are a useful predictor of children’s prospects for upward mobility today

Places that have produced good outcomes in the past typically tend to produce good outcomes a decade later, though the researchers caution that estimates should be combined with additional analyses and knowledge of areas that have changed substantially.

Finding 6: The new data uncover “opportunity bargains”—affordable neighborhoods that produce good outcomes for children

In other words, not all higher-opportunity neighborhoods have higher costs of living. The availability of low-rent, high-opportunity neighborhoods suggests that affordable housing policies could be redesigned to produce larger gains for children without increasing government expenditure, the authors write. More broadly, the existence of opportunity bargain areas shows that creating pathways to opportunity need not require reproducing conditions in highly affluent, expensive neighborhoods.

Going forward, Friedman and his colleagues hope researchers use the Opportunity Atlas to better target programs that aim to improve economic opportunities for disadvantaged children. They suggest that these data could inform the distribution of housing vouchers to higher-opportunity areas, placement of preschool programs, or eligibility for local programs or tax credits.

The full set of data, configurable by Census track, is freely available on the Opportunity Atlas website. Additional researchers are from Harvard University and the US Census Bureau.

Source: Brown University