A new test can determine whether Ebola is causing a patient’s symptoms in less than half an hour and is portable enough to take into the field, researchers report.

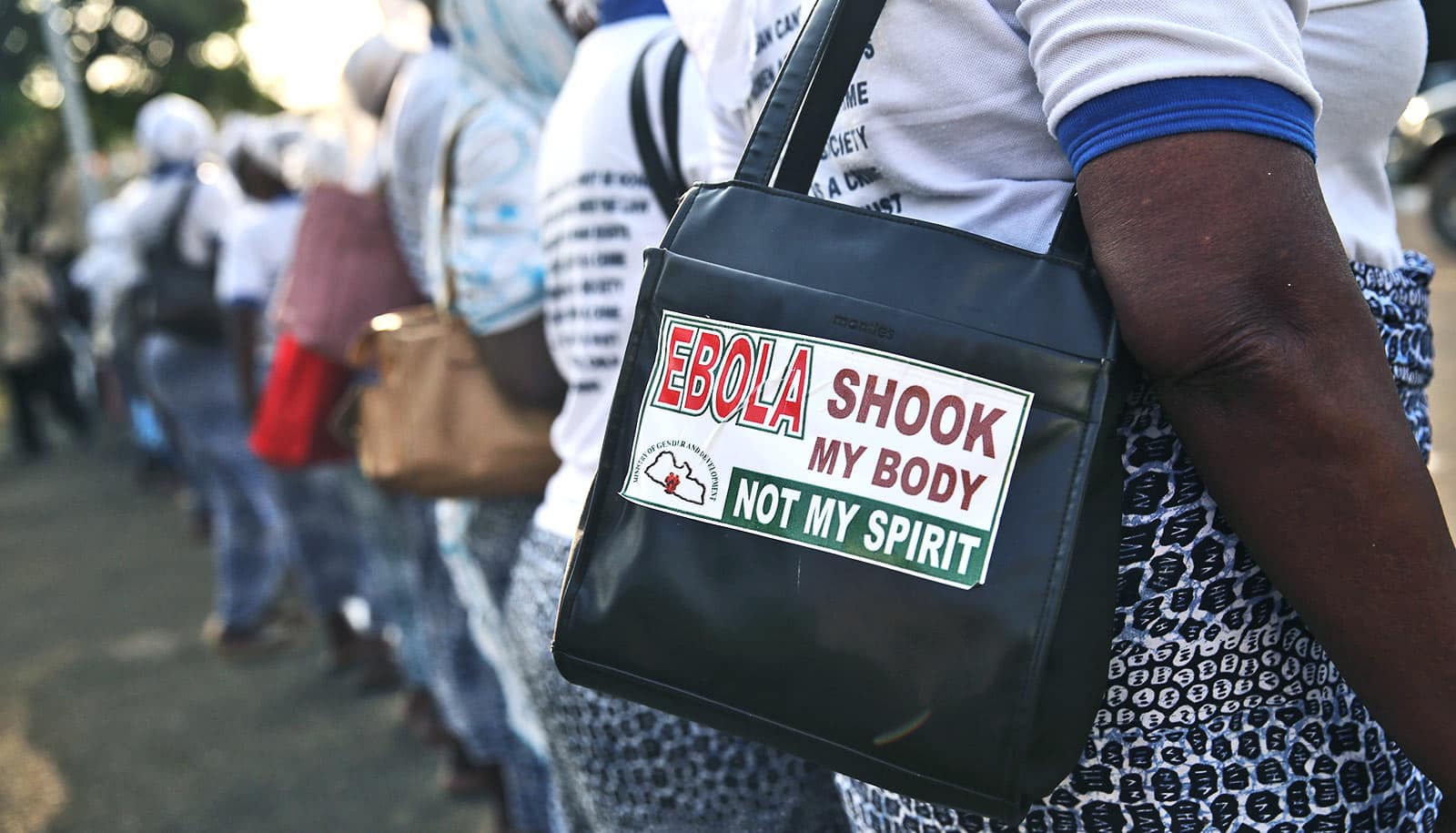

At a clinic in Liberia, people trickle in from the surrounding neighborhoods, shivering despite the warm air, reporting varying degrees of headaches and nausea. Many of them are anxious—it’s 2014 and an Ebola outbreak is underway and they fear the worst: that they, like some of their neighbors and loved ones, have contracted the highly fatal disease. One by one, they wait for a clinician to examine them, all the while mosquitoes float and buzz in the thick evening air.

During the early stages of Ebola, symptoms are often hard to distinguish from another disease endemic to the region, malaria, a mosquito-borne blood infection that a parasite causes. Without an instantaneous way of screening a patient’s blood, doctors may place people sick with malaria in quarantine, surrounded by other ill people who ultimately might, in fact, have Ebola and be highly contagious, instead of treating them with antimalarial medication.

That danger of being unable to diagnose Ebola—or malaria—in seconds or minutes, rather than hours or days, is one of the major deficiencies that contributed to the 2014–2016 West Africa Ebola crisis, according to the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation.

“The standard diagnostic tests that exist are very good, but they’re hard to do out in the field in the middle of an outbreak like we saw in West Africa,” says John Connor, an associate professor of microbiology at the Boston University School of Medicine. Instead, samples need to go to a facility capable of running the tests. “It could be several days between taking a sample and getting a diagnosis.”

When dealing with a fast-spreading, highly contagious, deadly disease like Ebola, those several days could mean the difference between containing an outbreak—or not.

Picking out pathogens

Connor and a team researchers came together to do something about it. Together, the team proposed an idea for a new kind of diagnostic that would bridge critical gaps in the field.

“We set out to create a rapid, point-of-care diagnostic that could look for malaria, Ebola, and other pathogens that are often found in these regions,” says Connor, a virologist at Boston University’s National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratory, which contains a Biosafety Level-4 laboratory that has been working with Ebola virus since August 2018.

As he reflects on the West Africa outbreak that prompted the last two years of his research efforts, Connor says better diagnostics are needed just as much now as ever. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Connor says, is “a smoldering outbreak… the largest outbreak that Congo has ever had and it’s looking like it’s not under control.”

While there are myriad ways to design rapid, portable diagnostics, the solution the team pursued was based on a test that they could store without refrigeration, which is typically hard to maintain along supply routes to rural outbreak areas. That’s why a compact diagnostic system built on magnetic beads and glass-encased gold nanoparticles was so appealing for the job.

The system, surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS), is based upon the idea that light scatters off of different types of molecules in distinct ways. Specific molecules have distinct light-scattering signatures, or unique barcodes, that can be detected. Although the barcodes can be weak on their own, adding gold particles makes the barcode easier to detect by boosting the light signal.

“Gold amplifies the barcode by about a million times,” says Connor.

Partnering with BD (Becton Dickinson), a global medical technology company which had developed SERS for other global-health-related applications, Connor and his collaborators helped design a system that would be able to differentiate between various barcodes of the malarial parasite and Ebola virus, as well as Marburg and Lassa viruses, two other deadly hemorrhagic fevers found in the same regions of Africa where Ebola outbreaks occur.

At the start of the test, a small sample of blood is mixed with magnetic beads coated in antibodies that attract each of the four infectious agents. If the blood contains malaria-causing parasites or Ebola, Marburg, or Lassa viruses, the pathogens glom onto the magnetic beads. At the same time, similar antibodies on glass-encased gold nanoparticles also attach to the pathogens, creating a link between the magnetic and gold beads. Then, inside a small machine, magnetic force concentrates the materials into one spot and a small laser beam hits them.

Fast diagnosis

Analyzing the barcode of light that flashes back from a sample, the machine provides a readout of the presence of malarial parasites or Ebola, Marburg, or Lassa viruses. If a sample contains more than one infectious agent, the test is able to identify them all.

From sample-taking to final readout, the entire process can be completed in a half hour or less. A paper that describes the development of the system, and shows experimental data showing its efficacy in animal and human blood samples, appears in Science Translational Medicine.

According to one of the study’s coauthors, Yanis Ben Amor of Columbia University, who partnered with lab technicians in Africa to test the device in the actual field, a great benefit is that “once the sample is added to the tube, there is no need to reopen the tube since all the reagents are already inside.” For the technicians carrying out the testing, “this was seen as a tremendous advantage in the context of highly infectious samples.”

Designed to go anywhere, the system’s components can be battery operated and can fit inside a backpack. How does Connor know that? He’s stuffed them inside his own standard-sized backpack to test out its portability.

“The implications for getting good diagnostics to remote places are huge,” says Connor, who is a corresponding author of the study.

Building community relationships

Connor says that the value of the diagnostic goes beyond identifying who has a contagious illness and who does not. It’s also about building stronger relations with the communities at risk of infection.

During an outbreak, “there is a strain between clinicians who are trying to assist with limited resources and the local community that is losing trust in their healthcare workers because they don’t have the appropriate tools and therefore can’t help to their fullest capability,” says Ben Amor.

If patients can rapidly get diagnoses and treatment for illnesses, it can foster trust while immediately helping clinicians identify who they should quarantine and who they should send home with antimalarial medicines.

The best scenario would be that clinicians are able to limit the time patients wait in crowded rooms, and therefore, decrease transmission opportunities, says Ben Amor.

Connor adds that the system could be custom-tailored to detect and differentiate virtually any combination of pathogens—bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic.

“The reason I find this system so promising is that it can diagnose more than one thing, which is important in the real-world context of infectious diseases,” Connor says. “The disease landscape is complicated and pathogens aren’t operating in isolation from one another.”

Additional researchers who contributed to this work came from Columbia University; the National Institutes of Health Integrated Research Facility; and clinical partners from Senegal and the Hemorrhagic Fever Lab at Université Gamal Abdel Nasser de Conakry, Guinea; as well as BD. The Paul G. Allen Foundation funded the work.

Source: Boston University