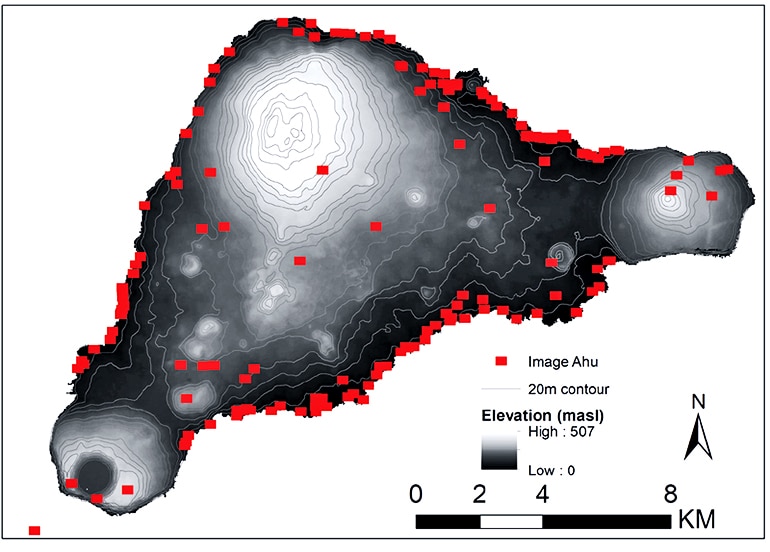

The ancient people of Rapa Nui, Chile, better known as Easter Island, built their famous ahu monuments near coastal freshwater sources, according to new research.

The island of Rapa Nui is well-known for its elaborate ritual architecture, particularly its numerous statues, or moai, and ahu, the monumental platforms that supported them. Researchers have long wondered why ancient people built these monuments in their respective locations around the island, considering the time and energy required to construct them.

The researchers used quantitative spatial modeling to explore the potential relations between ahu construction locations and subsistence resources, namely, rock mulch agricultural gardens, marine resources, and freshwater sources—the three most critical resources on Rapa Nui. Their results suggest that proximity to the island’s limited freshwater sources explains the locations of the ahu.

Mystery solved?

“Many researchers, ourselves included, have long speculated associations between ahu, moai, and different kinds of resources—water, agricultural land, areas with good marine resources, etc.,” says Robert DiNapoli, a PhD student in the archaeology program at the University of Oregon.

“However, these associations had never been quantitatively tested or shown to be statistically significant. Our study presents quantitative spatial modeling clearly showing that ahu are associated with freshwater sources in a way that they aren’t associated with other resources.”

The proximity of the monuments to freshwater tells us a great deal about the ancient island society, says Terry Hunt, a professor of anthropology at the University of Arizona and dean of the Honors College.

“The monuments and statues are located in places with access to a resource critical to islanders on a daily basis—fresh water,” says Hunt, who has been researching the Pacific Islands for more than 30 years and has directed archaeological field research on Rapa Nui since 2001.

“In this way, the monuments and statues of the islanders’ deified ancestors reflect generations of sharing, perhaps on a daily basis, centered on water, but also food, family, and social ties, as well as cultural lore that reinforced knowledge of the island’s precarious sustainability.

“The sharing points to a critical part of explaining the island’s paradox: despite limited resources, the islanders succeeded by sharing in activities, knowledge, and resources for over 500 years until European contact disrupted life with foreign diseases, slave trading, and other misfortunes of colonial interests,” Hunt adds.

Watery pattern

The researchers currently only have comprehensive freshwater data for the western portion of the island and plan to do a complete survey of the island in order to continue to test their hypothesis of the relation between ahu and freshwater.

“The issue of water availability, or the lack of it, has often been mentioned by researchers who work on Rapa Nui,” says Carl Lipo, a professor of anthropology and director of environmental studies at Binghamton University.

“When we started to examine the details of the hydrology, we began to notice that freshwater access and statue location were tightly linked together. It wasn’t obvious when walking around—with the water emerging at the coast during low tide, one doesn’t necessarily see obvious indications of water—but as we started to look at areas around ahu, we found that those locations were exactly tied to spots where the fresh groundwater emerges, largely as a diffuse layer that flows out at the water’s edge.

“The more we looked, the more consistently we saw this pattern. This paper reflects our work to demonstrate that this pattern is statistically sound and not just our perception.”

The paper appears in PLOS ONE.

Additional researchers contributing to this work are California State University, Long Beach; Penn State; and the University of Auckland.

Source: University of Arizona