Researchers have discovered a clue in Italian limestone that helps explain a mass extinction of marine life millions of years ago.

The findings may provide warnings about how oxygen depletion and climate change could affect today’s oceans.

“This event, and events like it, are the best analogs we have in Earth’s past for what is to come in the next decades and centuries,” says Michael A. Kipp, an earth and climate science assistant professor at Duke University.

Kipp coauthored the study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that measures oxygen loss in oceans leading to the extinction of marine species 183 million years ago.

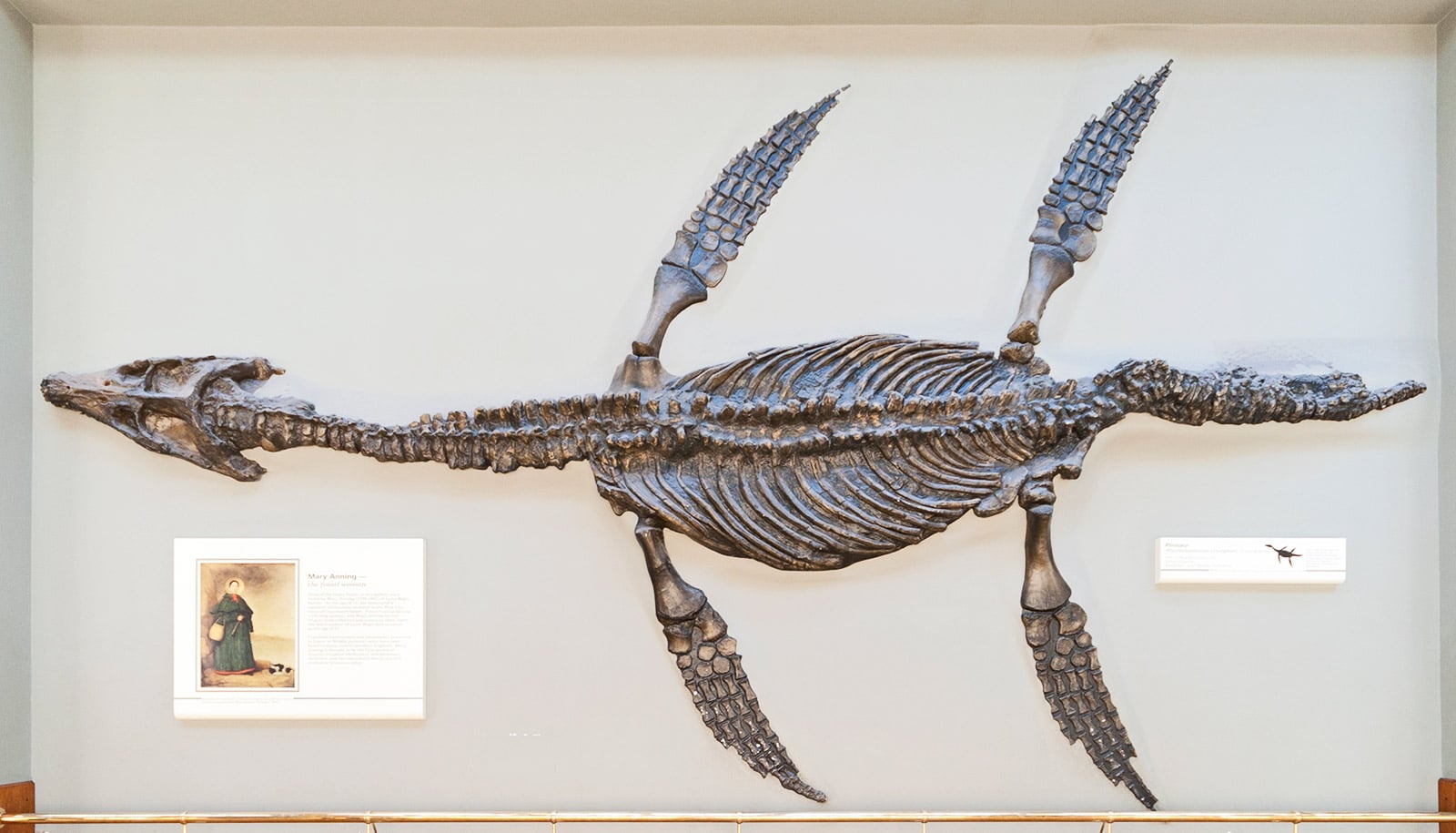

During the Jurassic Period, when marine reptiles like ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs thrived, volcanic activity in modern South Africa released an estimated 20,500 gigatons of carbon dioxide (CO2) over 500,000 years. This heated the oceans, causing them to lose oxygen.

The result was the suffocation and mass extinction of marine species.

“It’s an analog, but not a perfect one, to predict what will happen to future oxygen loss in oceans from human-made carbon emissions, and the impact that loss will have on marine ecosystems and biodiversity,” says coauthor Mariano Remírez, an assistant research professor at George Mason University.

Studying limestone sediment that carries chemicals dating back to the time of the volcanic outburst, the researchers were able to estimate the change in oxygen levels in ancient oceans.

At one point, oxygen was completely depleted in up to 8% of the ancient global seafloor, an area roughly three times the size of the United States.

Since the Industrial Revolution began in the 18th and 19th centuries, human activity has released CO2 emissions equivalent to 12% of what was released during the Jurassic volcanism.

But Kipp says that today’s rapid rate of atmospheric CO2 release is unprecedented in history, making it hard to predict when another mass extinction might occur or how severe it might be.

“We just don’t have anything this severe,” Kipp says. “We go to the most rapid CO2-emitting events we can in history, and they’re still not rapid enough to be a perfect comparison to what we’re going through today. We’re perturbing the system faster than ever before.”

“We have at least quantified the marine oxygen loss during this event, which will help constrain our predictions of what will happen in the future,” Kipp says.

The research appears in PNAS.

Source: Duke University