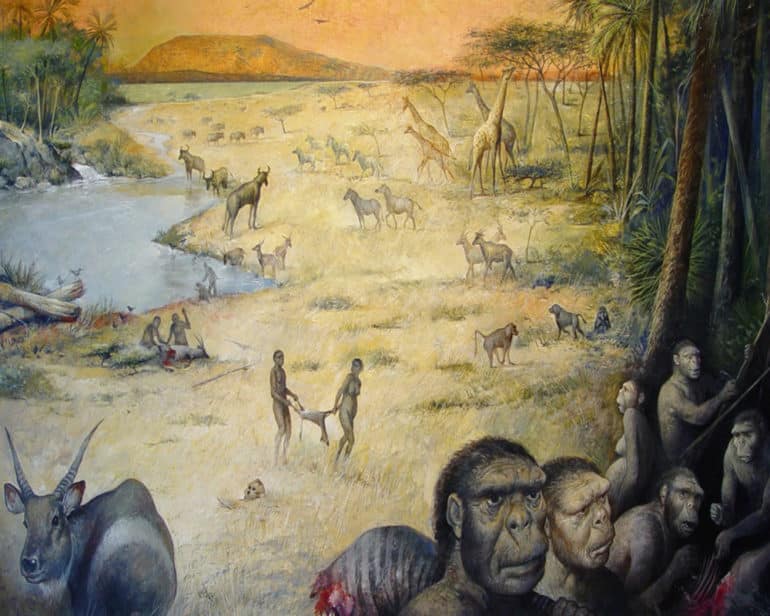

Scientists have pieced together an early human habitat in Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, and discovered that despite access to food, water, and shady shelter, the living 1.8 million years ago was far from easy.

These human ancestors, who looked like a cross between apes and modern humans, even had stone tools with sharp edges, but still had to eke out a tough living, says Gail M. Ashley, professor of earth and planetary sciences at Rutgers University. “It was a very stressful life because they were in continual competition with carnivores for their food.”

During years of work, researchers reconstructed the landscape on a fine scale, using plant and other evidence collected at the sprawling site. The landscape reconstruction will help paleoanthropologists develop ideas and models on what early humans were like, how they lived, how they got their food (especially protein), what they ate and drank, and their behavior, Ashley says.

Paleoanthropologist Mary Leakey discovered the site in 1959 and uncovered thousands of animal bones and stone tools. Through exhaustive excavations in the last decade, scientists collected numerous soil samples and studied them via carbon isotope analysis. The landscape had a freshwater spring, wetlands, woodland, and grasslands.

[Our ancestors made these stone tools 3.3 million years ago]

“We were able to map out what the plants were on the landscape with respect to where the humans and their stone tools were found,” Ashley says. “That’s never been done before. Mapping was done by analyzing the soils in one geological bed, and in that bed there were bones of two different hominin species.”

The two species of hominins, or early humans, are Paranthropus boisei—robust and pretty small-brained—and Homo habilis, a lighter-boned species. Homo habilis had a bigger brain and was more in sync with our human evolutionary tree, Ashley says. Both species were about 4.5 to 5.5 feet tall, and their lifespan was likely about 30 to 40 years.

“It was a very stressful life because they were in continual competition with carnivores for their food.”

The shady woodland had palm and acacia trees, but researchers don’t think the hominins camped there. Based on the high concentration of bones, the primates probably obtained carcasses elsewhere and ate the meat in the woods for safety.

In a surprising twist, a layer of volcanic ash covered the site’s surface, nicely preserving the bones and organic matter, Ashley says. “Think about it as a Pompeii-like event where you had a volcanic eruption.” A volcano about 10 miles from the site may have erupted and “spewed out a lot of ash that completely blanketed the landscape.”

[Is your Neanderthal DNA making you depressed?]

At the site, scientists found thousands of bones from giraffes, elephants, and wildebeests, swift runners in the antelope family. The hominins may have killed the animals for their meat or scavenged leftover meat. Competing carnivores included lions, leopards, and hyenas, which also posed a threat to hominin safety.

Paleoanthropologists “have started to have some ideas about whether hominins were actively hunting animals for meat sources or whether they were perhaps scavenging leftover meat sources that had been killed by say a lion or a hyena,” Ashley says.

“The subject of eating meat is an important question defining current research on hominins. We know that the increase in the size of the brain, just the evolution of humans, is probably tied to more protein.” They may have also eaten hominins’ food also may have included wetland ferns for protein and crustaceans, snails and slugs.

Scientists think the hominins likely used the site for a long time, perhaps tens or hundreds of years, Ashley says. “We don’t think they were living there. We think they were taking advantage of the freshwater source that was nearby.”

The study is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Researchers from Penn State, the Geological Institute in Zurich, Switzerland, and Complutense University in Madrid, Spain contributed to the work.

Source: Rutgers University