When E. coli bacteria leave their host’s digestive tract, they must adapt to sudden starvation. New research suggests that’s why they shrink.

Close examination of nutrient-deprived E. coli under the microscope—a routine process in a lab that studies bacterial cell size—reveals cells that looked different, and that these differences are related to their ability to survive.

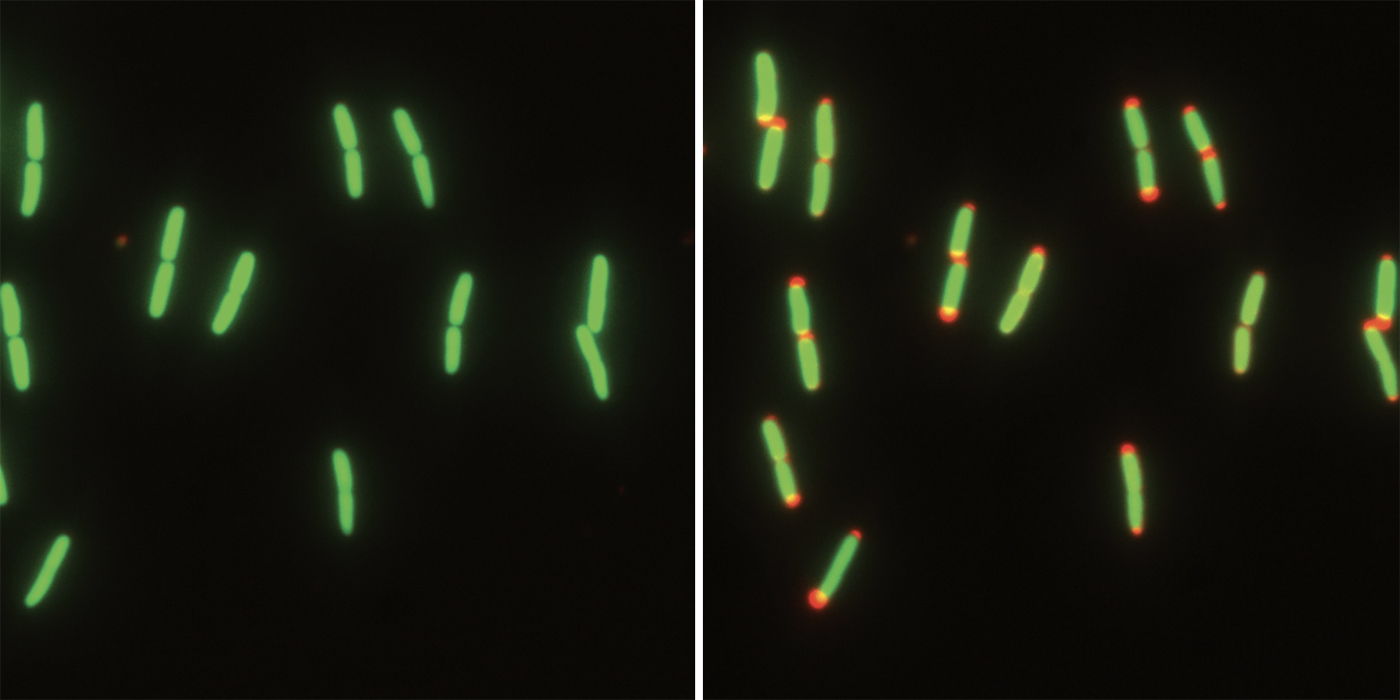

“Their cytoplasm shrank. As it shrank, the inner membrane pulled away from the outer membrane and left a big space at one end of the cell,” says Petra Levin, professor of biology in at Washington University in St. Louis, whose postdoctoral scientist, Corey Westfall, and undergraduate student, Jesse Kao, first made the observation.

The space to which Levin refers, between the bacteria’s inner and outer membranes, is called the periplasm. In collaboration with Kerwyn Casey Huang, professor of bioengineering and of microbiology and immunology at Stanford University, and postdoctoral scientist Handuo Shi, Levin found an unexpected developmental response to starvation—one that may be keeping E. coli alive until they find their next buffet.

The work appears in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Why do E. coli shrink?

The biologists showed that when E. coli cells lack nutrients, the cytoplasm becomes more dense as its volume decreases, probably because of water loss. At the same time, the periplasm increases in volume as the inner membrane pulls away from the outer membrane.

“Although we don’t know for sure yet, we think that the cell is concentrating the nutrients in the cytoplasm so that it can keep running metabolism at a high rate,” Levin says. “Perhaps this is an adaptation to E. coli’s constantly and rapidly changing lifestyle, in which it knows that each environment is temporary.”

Rapid rebound

The shrinking is reversible, the scientists found. Once they transferred the starving bacteria into a nutrient-rich medium, the inner membrane and the cytoplasm expanded. The bacterial cells rapidly rebounded from starvation, especially when E. coli received their favorite carbon source, glucose. And, importantly, if the Tol-Pal system was intact.

The Tol-Pal system is a critical cellular machinery composed of proteins that connect the outer membrane to the inner membrane. But its function has been understudied. As the inner membrane expands, the Tol-Pal system helps to reconnect it with the outer membrane, the scientists speculate. When the Tol-Pal system was absent, the internal contents of the cells bled out.

“We speculate that Tol-Pal acts as the zipper slider, helping the inner membrane zip into the outer membrane coat during recovery,” Levin says.

What happens to the transmembrane proteins, embedded in both the inner and outer membrane, when the inner membrane pulls away from the outer membrane? Do they get ripped apart? Levin and colleagues don’t yet know but hope to answer these questions in the future.