Measures to ban e-cigarettes, intended to prevent teen vaping, could make it tougher for tobacco smokers to quit, two experts argue.

E-cigarettes have been at the center of a heated debate among policymakers, parents, and the public health community. San Francisco recently became the first US city to ban the sale of e-cigarettes.

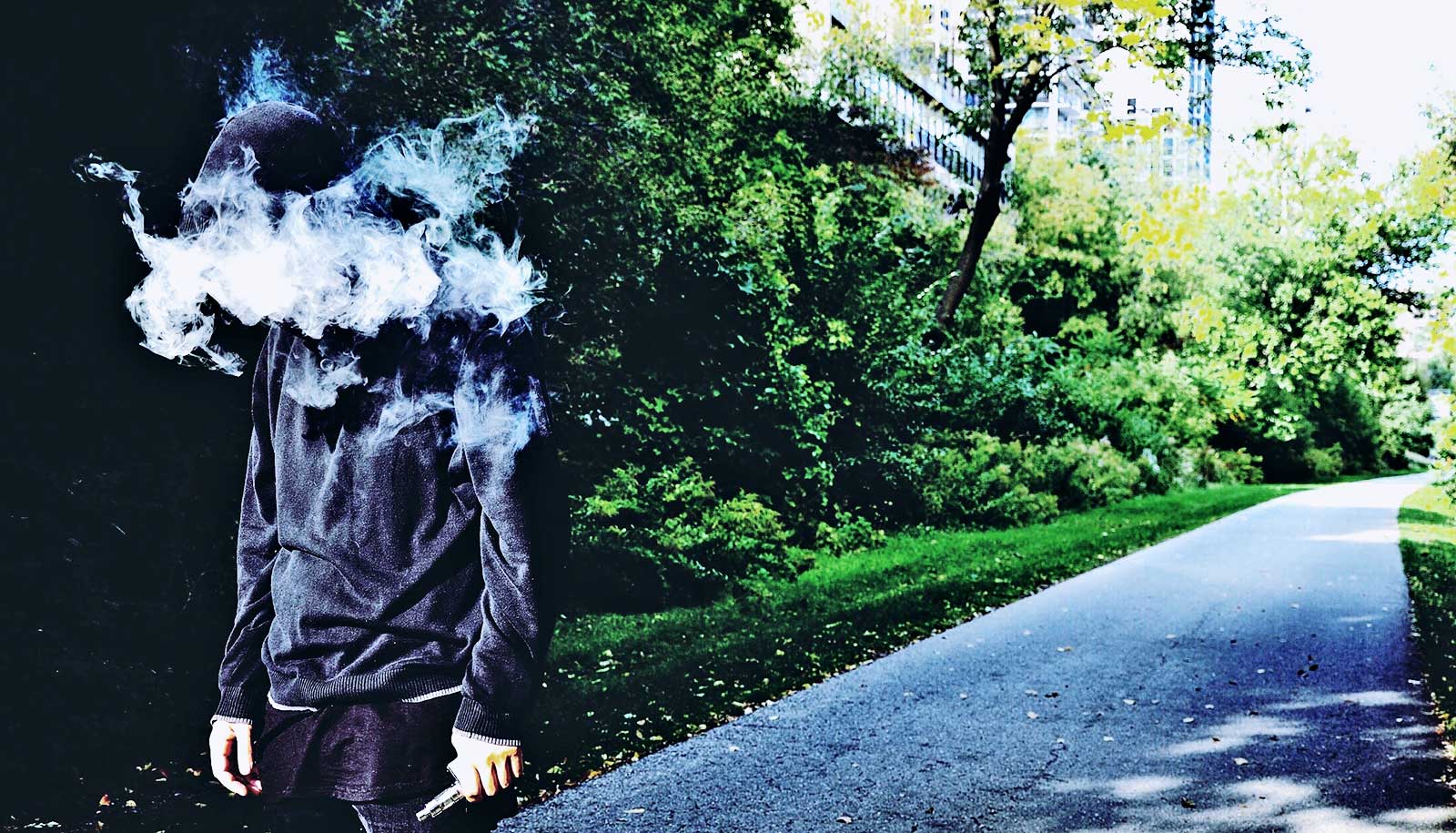

On one hand, research shows that e-cigarettes are substantially safer than cigarettes, delivering nicotine through a vaporized mist rather than burning tobacco—which creates cancer-causing toxins.

On the other hand, a surge in youth vaping raises questions about teens getting hooked on nicotine and what the long-term health impact of e-cigarettes will be. But since vaping products have not been on the market long enough, health experts may not know the precise effects for decades.

David Abrams and Ray Niaura—both professors of social and behavioral sciences at the New York University College of Global Public Health and co-directors of the Tobacco Research Lab, coauthored a paper in 2017 in Tobacco Control that showed if most American smokers switched from cigarettes to vaping over the next 10 years, it could save as many as 6.6 million lives.

Here they discuss the potential ramifications of the San Francisco e-cigarette ban on public health.

How have bans been used to address other public health issues?

Abrams: The prohibition of alcohol in the 1920s and early 1930s did not work well—in fact, it was disastrous, leading to a robust black market with bootlegging, crime, and money laundering. It was repealed in 1933. Today, we have strict age checks and enforcement of laws to suppress underage drinking as much as possible, but society tolerates the reality that some teens will take risks: about 30 percent say they used alcohol in the past month. We balance the risks, but can’t eliminate or ban all teen alcohol use.

Likewise, the “just say no” campaigns and “scared straight” programs on drug prevention may have done more harm than good. Most studies of the anti-drug program D.A.R.E. have found no benefit to the intervention, and some have even shown that teens who take part in these programs are more likely to smoke and drink, rather than being deterred. So, the net public health impact was negative, despite the well-meaning intentions.

Niaura: A harm reduction approach, which aims to minimize negative consequences rather than promote abstinence, may be more effective than prohibition at addressing certain public health issues.

Take sex education as an example. Comprehensive sex education explains that abstinence is the only guaranteed way to prevent pregnancies and STDs, but it also gives guidance on how to reduce risks for teens who choose to be sexually active. Harm reduction can embrace abstinence and give practical advice to those who won’t abstain.

Unfortunately, abstinence-only sex education is still common, and it has consequences. In a recent study, teens who signed a pledge to not have sex before marriage were more likely to contract an STD and get pregnant out of wedlock, a result of abstinence-focused messaging that downplays the effectiveness of condoms and other contraceptives.

A growing body of research points to using harm reduction for smoking cessation. While quitting smoking—or never starting—is ideal, if you’re going to smoke, you can minimize your exposure to the toxins in cigarettes by switching to safer nicotine products like e-cigarettes.

What are the potential consequences of banning e-cigarettes in a city?

Abrams: Smokers would have to use regular cigarettes or go to great lengths and greater expense to get their vape products—for instance, traveling to a nearby town to buy e-cigarettes, or purchasing them from a black market created by a ban. Basically, it would help keep people smoking deadly cigarettes and the little cigars or cigarillos that appeal to teens. That is the opposite of what we want.

Who benefits from an e-cigarette ban? Who loses?

Niaura: Very few teens will benefit. Most teens who do not already use other tobacco products will not vape either.

Abrams: All tobacco smokers lose, especially populations with the highest smoking rates, including those in the LGBTQ+ community, lower income and uninsured groups, substance users, the mentally ill, and others in society who may have no political voice. They all suffer if we take away less harmful products and make them more expensive and harder to get.

The FDA has taken some steps to begin regulating e-cigarettes, although the San Francisco ban seems to be a response to that process moving too slowly. What role can the federal government play here?

Niaura: The FDA can—and should—stick to its plans to find ways to make regular cigarettes less appealing. For instance, by reducing nicotine levels—and reviewing and approving “reduced risk” products like e-cigarettes that follow the appropriate application process. Applicants must demonstrate that their products are significantly safer than smoking tobacco, but this requires adequate research that follows FDA guidelines.

The FDA must do what it can to streamline and accelerate this process without sacrificing research quality or standards.

Is it inconsistent to ban the sale of e-cigarettes when cigarettes, which we conclusively know are dangerous to our health, are readily available?

Niaura: It makes no sense to keep deadly smoked tobacco products on store shelves but say that vaping products must be taken off. Why leave the most dangerous products and take away less harmful ones? That is a public health disaster for all cigarette smokers, even if it makes political sense to some who are saying they are protecting teens.

Abrams: It’s also a human rights issue: smokers should not be deprived of accurate information that vaping is much less harmful than smoking. The best results for switching from cigarettes to e-cigarettes comes from smokers who stick with it until they find a product that works for them.

There is strong evidence that vape products, when used regularly, can double the chances of someone quitting cigarettes completely compared to nicotine replacement therapy like gums, patches, and lozenges that help some smokers quit.

Source: NYU