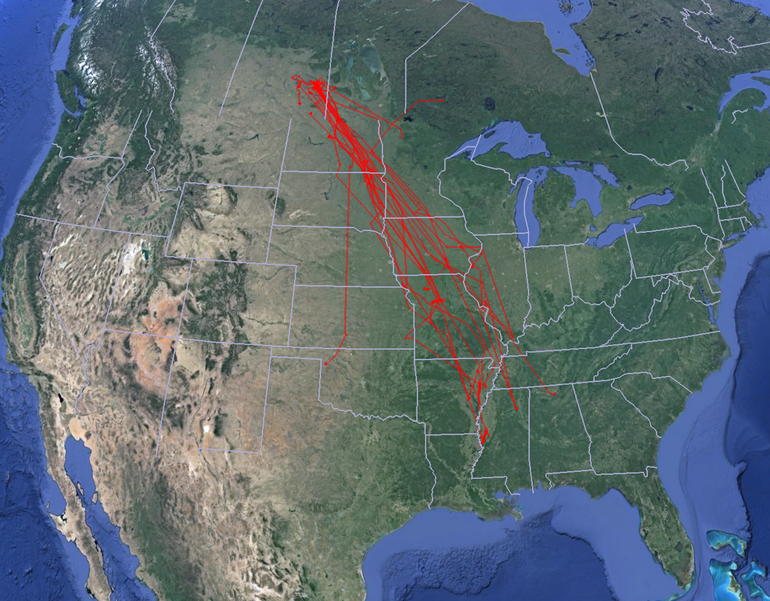

Researchers have used satellite tracking technology to monitor Mallard duck migration from Canada to the American Midwest and back again.

Their findings show that 2011-2012 migrations extensively used public and private wetland conservation areas.

Scientists now have baseline information for future research into what influences the ducks’ migration flight paths, landing site selection, and foraging behavior. The data will also be useful to conservationists looking for ways to ensure healthy duck populations into the future.

The research shows private lands enrolled in the USDA’s Wetland Reserve Program (WRP) have become a critical component of the ducks’ migrations, says Lisa Webb, cooperative assistant professor of wildlife at University of Missouri and research ecologist with the USGS Cooperative Research Unit. The WRP provides landowners with technical and financial support for restoring and maintaining wetland areas that have conservation benefits.

Migratory ducks also use sanctuaries on public areas, such as state wildlife management areas and the National Wildlife Refuge System extensively.

Tracking ducks from orbit

The project attached small solar-powered tracking devices to the ducks, which transmitted their locations every 4 hours. Data bounced off a satellite and then went to the researchers who monitored the ducks’ progress in real time.

[related]

“This allowed us to evaluate their behavior and biology on an exceptionally detailed scale throughout their annual migration cycle,” says Dylan Kesler, co-investigator and assistant professor of fisheries and wildlife.

“Previously, we only knew when the birds left and when they arrived and little else. Now, we have an extensive dataset from which to understand the role of different habitats and other factors in migratory populations. We can begin to understand migration in a way that it has never been understood before.”

Kesler points out that scientists also now know more about the pre-migratory feeding habits of the ducks. The ducks’ ability to gain weight before their long flights is an important factor in how many will make it to their northern breeding grounds and southern wintering stations.

Identifying ways to support duck populations is important because more than 50 percent of American wetlands have been lost since 1800, says Kesler. This loss has affected migratory bird populations and migration timing and routes, he says.

The mallard is probably the most familiar and abundant duck in North America. The male has a green head and chestnut breast while females are mottled brown. Both sexes have a blue speculum (wing patch) bordered on both sides by white.

The mallard nests in the spring throughout Canada and northern US, with eggs hatching in April and May. They migrate to a winter home in the Midwestern and southern US in September and October. They take off back to Canada in February and March.

The National Wildlife Refuge System is the largest protected area network in North America specifically designated for wildlife conservation and includes more than 150 million acres stretching from Alaska to the Caribbean.

The program is designed to maintain wetlands and other wildlife habitat in areas where surrounding lands have been converted to golf courses, cities, and agriculture.

Better conservation areas

The new dataset is so extensive that William Beatty, postdoctoral fellow of University of Missouri Fisheries and Wildlife Sciences, is using the information as the basis for a computer model to understand future migrations and the effect that human populations, physical obstructions, agriculture, and conservation areas may have on migratory bird populations.

The satellite tracking data showed the researchers something not known until now—during their migrations ducks forage for food up to 20 miles away from their roosting areas. Beatty says this discovery shows how the conservation areas being used by the ducks can be improved.

He recommends establishing multiple types of conservation areas in selected locations to promote wetland habitat diversity to give birds a variety of food choices.

“The role of habitat conditions during the non-breeding season—fall migration, winter and spring migration—is not fully understood,” Webb says.

“Now that scientists and conservationists better understand which habitat features are important to mallards during the non-breeding season, we can begin to consider how results may help conservation agencies as they decide where to restore new wetland habitat for waterfowl.”

The research results appear in Biological Conservation.

Source: University of Missouri