A new device could help doctors with disabilities overcome the challenges of performing standard patient examinations.

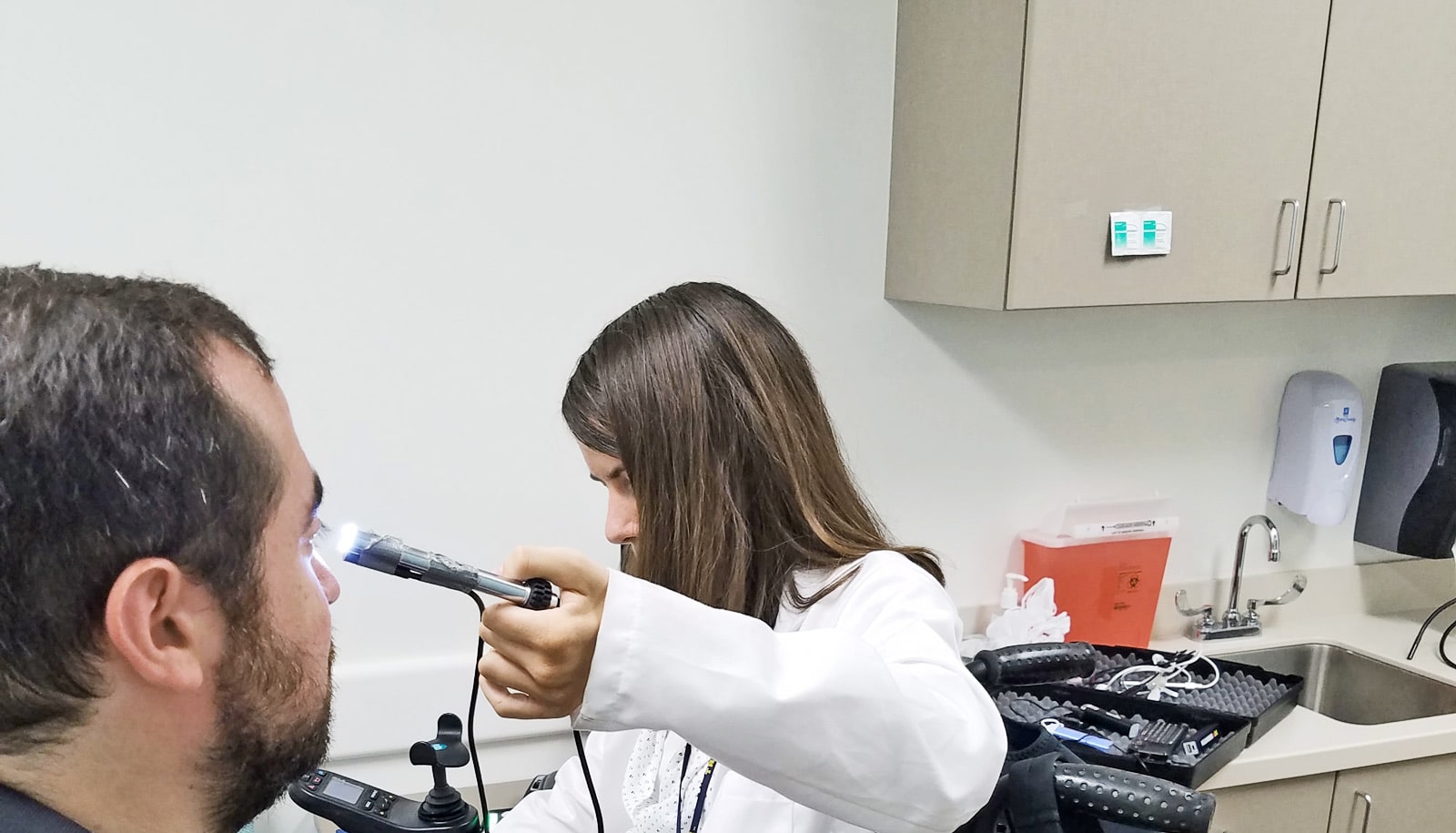

Instead of using a traditional stethoscope or otoscope to examine a patient, Molly Fausone, a physician-in-training at the University of Michigan, uses a long, flexible wire with a camera at its tip. A live video feed plays diagnostic information back on her cell phone.

After a swimming accident at age 15 left Fausone paralyzed from the chest down with limited use of her hands, she wanted to stay away from hospitals as much as she could. She spent the first half of her college career at Stanford University exploring her options, thinking maybe she would become an engineer.

“I wanted to find something I was excited about, and when I took a course in human biology I knew that was what I wanted to do,” she says.

She thought about a career in biological research but medicine was still in the back of her mind. After graduation, she taught biology for a year at Stanford and enjoyed working closely with students.

“I slowly made my way back to medicine after my injury, working in a free clinic in Chicago for two years after teaching at Stanford. I had reached the conclusion that medicine was a good combination of research, interpersonal interactions, and teaching, too,” she says.

Fausone is now a third-year medical student and is determined to become a doctor despite the physical limitations of her disability.

Few doctors with disabilities

Though doctors treat patients with all kinds of disabilities, illnesses, or injuries, doctors themselves rarely have disabilities. While more than 20 percent of Americans live with disabilities, under 2 percent of practicing physicians do.

“Very few universities accept first year medical students who are paraplegic or quadriplegic,” says David Burke, professor and interim chair of the human genetics department. “Historically, certain people have been dissuaded from areas of medicine.

“Most of the imaging systems that doctors use require the doctor to be up against the patient’s ear or mouth, or nose. The physician’s eye has to be collinear with the object being examined. If the patient is lying down, going to the other side of the patient isn’t always possible, as some examination rooms aren’t big enough to take a wheelchair around both sides,” Burke says.

Recognizing that even a straightforward patient examination can pose a major challenge, Burke and David Lorch, program director for the Global Challenges for the Third Century Initiative on Deep Monitoring, started brainstorming, eventually creating a device that allows doctors with disabilities to examine a patient’s skin, eyes, ears, nose, throat, and mouth from a distance.

“Being able to align my eye with a patient’s ear or nose isn’t the critical component of being a doctor,” Fausone says. “The crux of it is finding a problem, interpreting it, and treating it.”

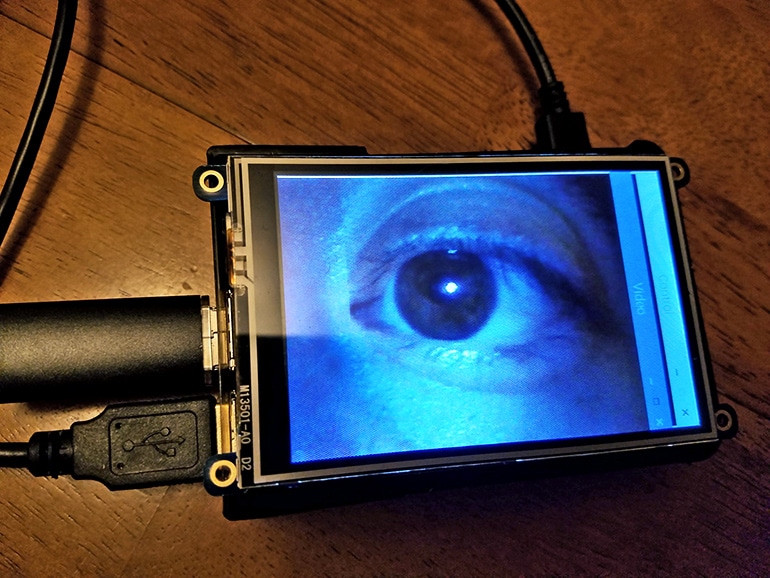

The device has a long, flexible wire and a camera in its speculum, which is the cone-shaped piece at the end of a standard medical otoscope used to examine a patient’s ears. The system displays images on any mobile device.

Other features on the way

Burke and Lorch are working on adding other features. Adding video recording, for example, would provide a variety of opportunities for all doctors, such as looking back at older recordings to see if a condition has changed, sending the recording to a specialist, or using it to teach medical students.

“We now have a set of low-cost technologies that make it easier to build machines that can capture high-quality information from patients and then send it, rather than the physician and the patient needing to physically be in the same place at the same time,” Burke says.

“I think this will be particularly important for remote and underserved populations, places where there are a low density of physicians, especially specialists.”

The live video stream can enhance and zoom in on images to facilitate the physician’s examination. The device has its own WiFi network to ensure recordings are sent safely.

Body feedback could make assisted walking easier

Another challenge Fausone faces is standard neurological examinations that require the physician to exert significant force, such as when the examiner asks the patient to press against his or her hand with the same amount of force.

“We’re using three dimensional tracking technologies so that we can find a way for her to measure a person’s strength and mobility without her having to make direct contact with the patient,” Lorch says.

The device would capture the amount of force a patient exerted, allowing for more accurate measurement compared to a physician’s subjective assessment of the neurological examination. Both Burke and Lorch also note this device could help create more standardization in the medical field.

The goal is for all physicians to use these devices, regardless of whether they have a physical limitation or disability. The option to use them could broaden the opportunities of a medical career for many who otherwise would not be able to meet its demands.

“When we think about disability, we typically think about physical disabilities,” says Donna Omichinski, center coordinator for the University of Michigan Rehabilitation and Engineering Research Center, Technology Increasing Knowledge: Technology Optimizing Choice (TIKTOC RERC).

“There are also invisible disabilities such as hearing impairment or neurodevelopmental disability. Finding ways to adapt and accommodate training within medical professions is not just an issue for doctors with disabilities.

Clothes are more than a hassle for people with disabilities

“This can be an issue for nurses, physical therapists, physician’s assistants, etc. Oftentimes, the environment becomes the factor that limits a person’s function and accessibility, and technology can serve as a bridge to these barriers.”

A grant program from Third Century Initiative Global Challenges funded the force and movement assessing device. The device for examining a patient’s skin, eyes, ears, nose, throat, and mouth is primarily funded by the TIKTOC RERC small grant program.

Source: University of Michigan