A new study suggests one possible reason why reproduction slows with age.

The researchers report that older worms are less efficient at repairing broken DNA strands while making egg cells—part of a process that’s essential for fertility.

The findings appear in PLOS Genetics.

Each sperm or egg cell has only half the number of chromosomes found in a regular cell. During meiosis, the cell division process that forms sperm and eggs, the parent cells must evenly divide their DNA. The costs of error can be high, since incorrectly divided chromosomes are a major cause of birth defects.

To get it right, cells use a surprising strategy: They deliberately break their strands of DNA, and then repair them.

“It’s one of the most amazing processes in biology,” says Erik Toraason, a former graduate student in the lab of Diana Libuda at the University of Oregon who led the work. The repair process “physically locks the chromosomes together and provides an organization point” that ensures that the chromosomes are divided evenly.

Toraason wanted to understand how aging affects those processes. Eggs lose their viability relatively early in an organism’s lifespan, but “the reason these cells are so susceptible to aging is not well understood,” says Toraason, who is now a postdoctoral researcher at Princeton University.

“But one of the factors that’s considered to be important is genome repair, and the idea that that might decline, leaving oocytes—developing eggs—vulnerable to defects,” Toraason says.

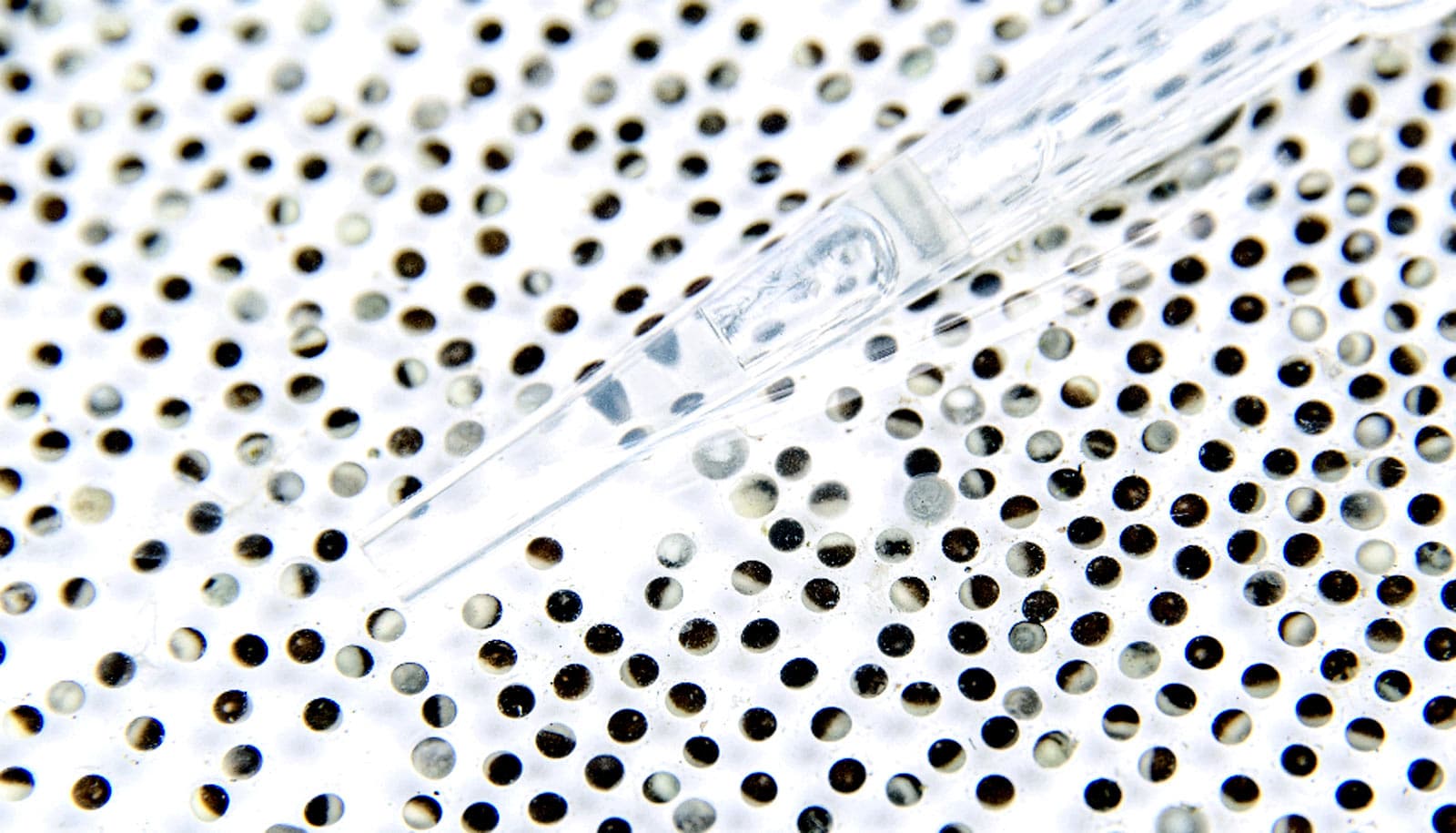

Worms proved to be an ideal testing ground for those questions. C. elegans worms are usually hermaphroditic, meaning each worm produces both eggs and sperm. But thanks to a genetic mutation that nixes sperm production, researchers can create egg-producing worms that are functionally female.

Toraason and research assistant Vikki Adler used that trick to separate the effects of aging from the effects of running out of sperm, which happens normally as hermaphroditic worms age and also leads to a decline in fertility.

Running out of sperm seemed to affect the rate at which the hermaphroditic worms created breaks in their egg cell DNA, the researchers found. But the ability to repair DNA breaks declined with age even in the female worms, independent of sperm levels.

“We found that that forming breaks is altered when you run out of sperm, but break repair is only affected by the aging process, not sperm,” Libuda says.

The team doesn’t yet know why this process changes with age, but at least for worms, it could be related to a shift in resources.

In worms that have used up all their sperm, unfertilized oocytes sometimes become a food source for offspring. Since the oocytes aren’t being used for reproduction, the worms no longer need to spend resources breaking and repairing their DNA.

Source: Laurel Hamer for University of Oregon