A new study assesses rates and routes of possible infectious disease transmission during flights.

An infectious passenger with influenza or other droplet-transmitted respiratory infection will most likely not transmit infection to passengers seated farther away than two seats laterally and one row in front or back on an aircraft, the new research indicates.

Vicki Hertzberg, professor at Emory University’s Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing and Howard Weiss, professor in the School of Mathematics at the Georgia Institute of Technology, led tracking efforts in their FlyHealthy study, developing a model that combines estimated infectivity and patterns of contact among aircraft passengers and crew members to determine likelihood of infection.

FlyHealthy team members monitored specific areas of the passenger cabin, and made five round trips from the East to West Coast recording movements of passengers and crew. In addition, they collected air samples and obtained surface samples from areas most likely to harbor microbes. They leveraged the movement data to create thousands of simulated flight scenarios and possibilities for direct exposure to droplet-transmitted respiratory diseases.

“Respiratory diseases are often spread within populations through close contact,” explains Hertzberg. “We wanted to determine the number and duration of social contacts between passengers and crew, but we could not use our regular tracking technology on an aircraft. With our trained observers, we were able to observe where and when contacts occurred on flights. This allows us to model how direct transmission might occur.”

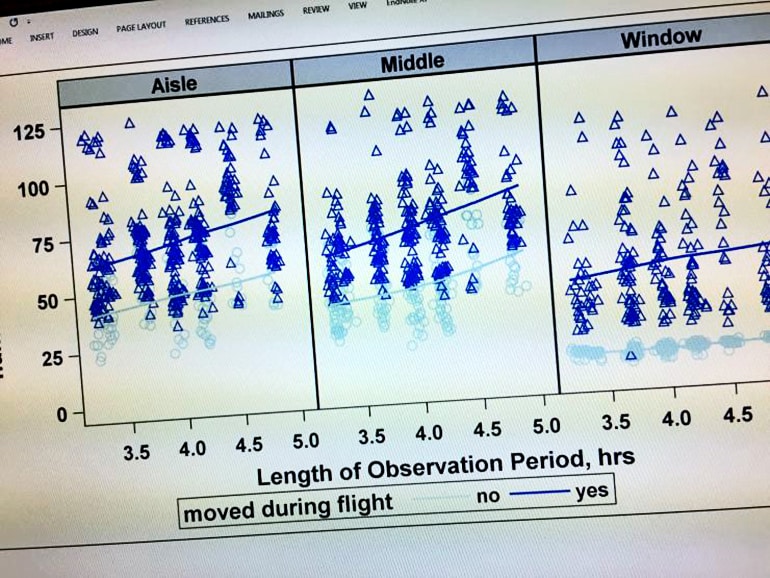

“We now know a lot about how passengers move around on flights. For instance, around 40 percent of passengers never leave their seats, another 40 percent get up once during the flight, and 20 percent get up two or more times. Proximity to the aisle was also associated with movement. About 80 percent of passengers in aisle seats got up during flights, in comparison to 60 percent of passengers in middle seats and 40 percent in window seats. Passengers who leave their seats are up for an average of five minutes,” Hertzberg says.

The researchers also point to fomite transmission—exposure to viruses that remain on certain surfaces such as tray tables, seat belts, and lavatory handles—as additional likely contributors to disease transmission. They provide public health recommendations to help prevent the spread of infectious disease.

How to avoid spreading the flu at work

“We found that direct disease transmission outside of the one-meter area of an infected passenger is unlikely,” explains Weiss. Respiratory infections can also be transmitted indirectly through contact with an infected surface. This could happen if a sick passenger coughs into their hand, and later touches a lavatory surface or overhead bin handle.

“Passengers and flight crews can eliminate this risk of indirect transmission by exercising hand hygiene and keeping their hands away from their nose and eyes.”

The study only evaluated the potential spread of infectious agents on an aircraft. Transmission could also occur at other points in a passenger’s journey, underscoring the need to maintain healthy habits, Weiss adds.

Complete findings of the study appear in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Funding for the research came from Boeing.

Source: Georgia Tech