Diabetes, age-related health conditions, and other metabolic disorders can lead to a buildup of cholesterol in the retina, find researchers.

The cholesterol buildup tends to crystalize and contribute to the development of diabetic retinopathy.

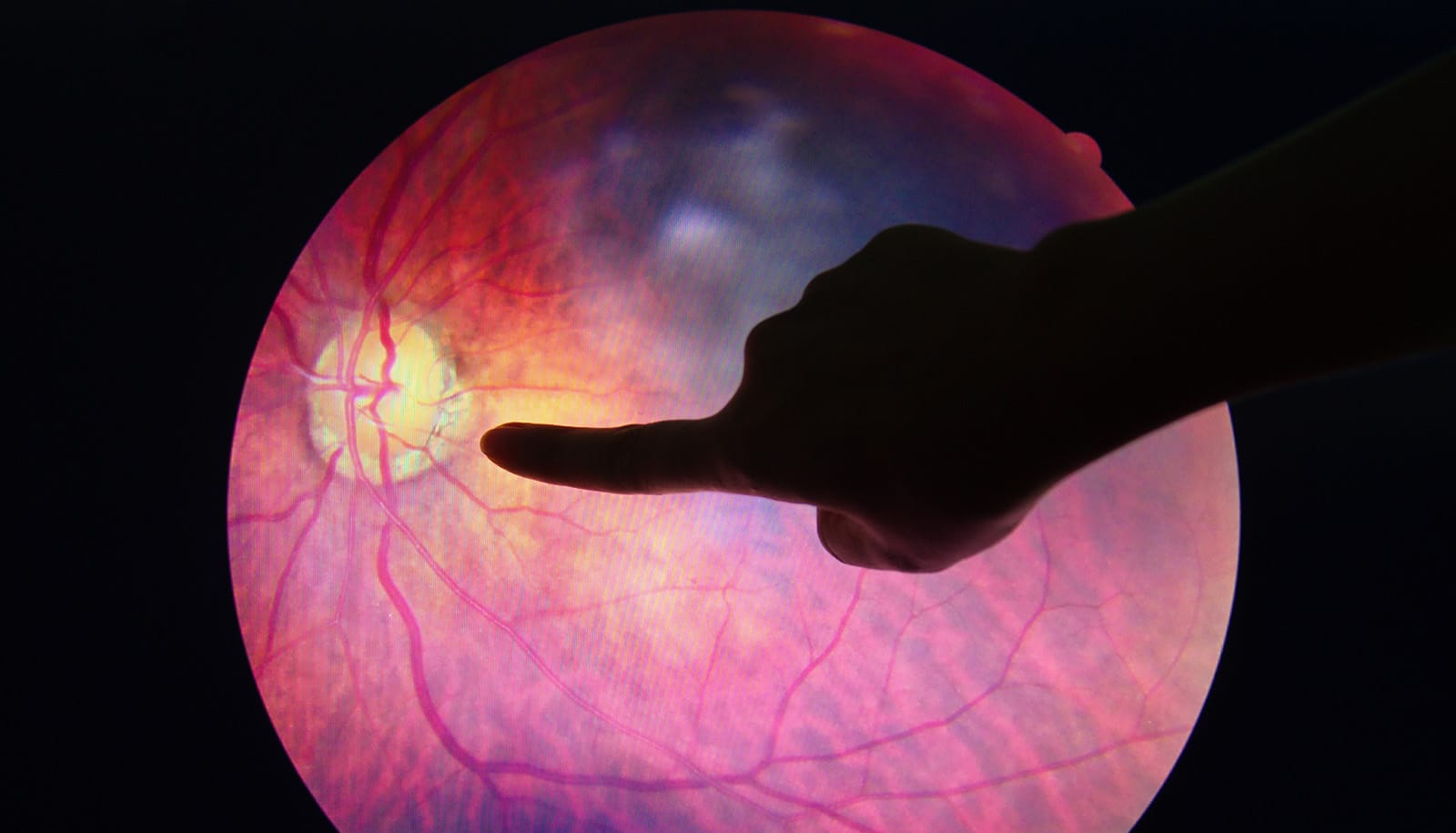

Crystalized deposits are very reflective and can be seen in images of the retina. This is important because noninvasive retina evaluations can be done by most optometrists, creating an opportunity for earlier diagnosis for more people.

“Retinopathy is the leading cause of preventable blindness and one of the most feared complications of type 1 and type 2 diabetes,” explains Julia Busik, professor emeritus of physiology at Michigan State University. “Within 20 years of developing diabetes, every individual with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes will have some degree of retinopathy. Current treatment approaches are very invasive and are only directed at the very late stage of retinopathy.”

“We are actively pursuing what can be done to lower cholesterol in the retina,” says Tim Dorweiler, a doctoral candidate in the molecular, cellular, and integrated physiology program at Michigan State and first author of the paper. “The retina is a very isolated organ, just like the brain, and both have a blood barrier that separates them from the rest of the body. This is what makes the retina hard to study and extremely complex.”

George Abela, chief of Michigan State’s Division of Cardiology, says that these cholesterol crystals are like the crystals found in atherosclerotic plaque that can form in arteries and cause heart attacks, a finding discovered in his lab. He helped the research team identify ways to scan retinas using modified tissue preparation for scanning electron microscopy. This also helps researchers analyze the composition of the crystals, which typically result when there is too much cholesterol in one place.

There is also hope that new treatments to address crystals formed by cholesterol could be less invasive than current options for diabetic retinopathy. And there are questions about other areas of the body where these crystals could be treated to prevent other diseases.

Their findings appear in the journal Diabetologia. Additional contributors are from the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Case Western Reserve University, and Western University of Health Sciences.

The study had funding from the National Eye Institute.

Source: Dalin Clark for Michigan State University