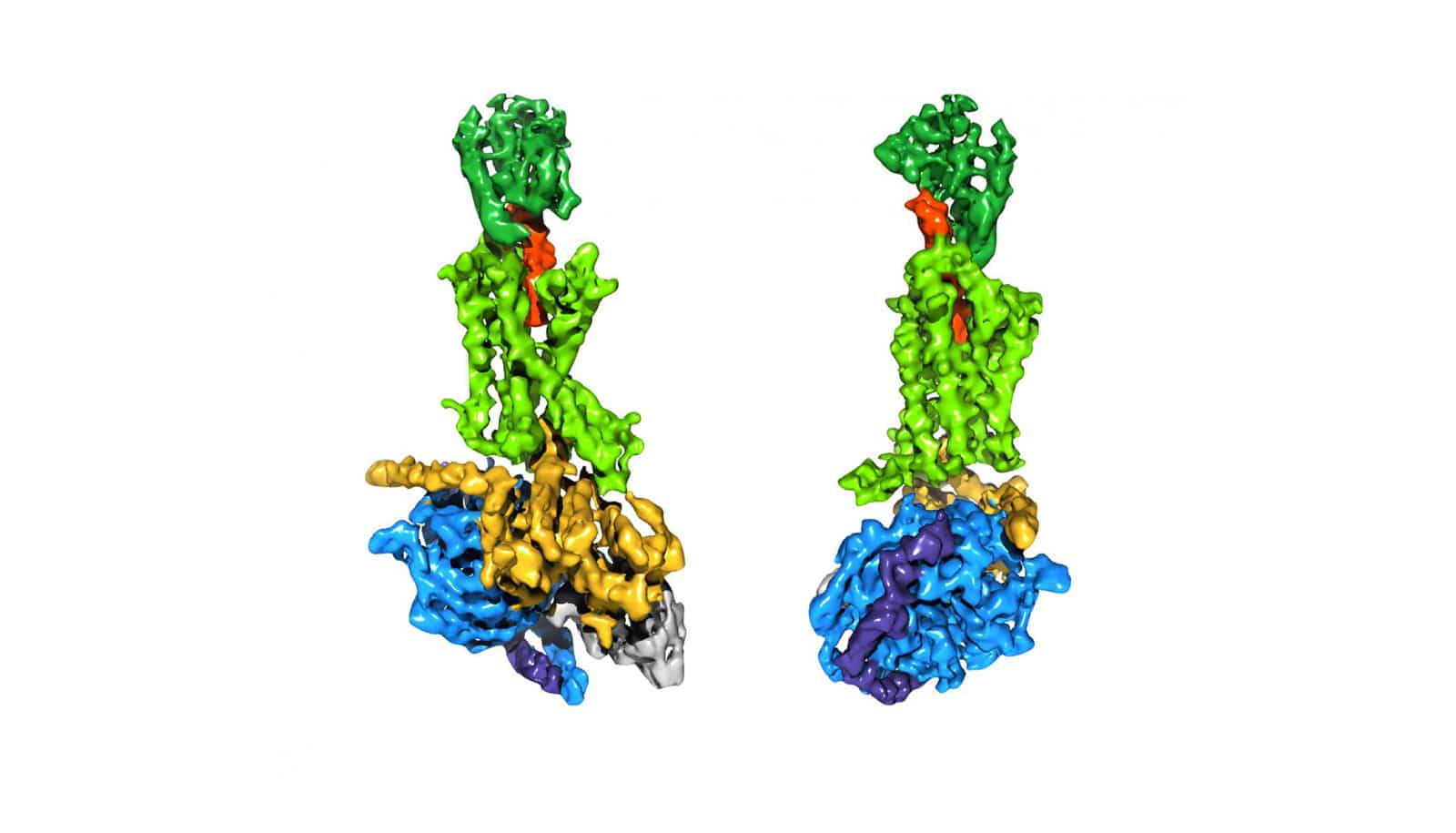

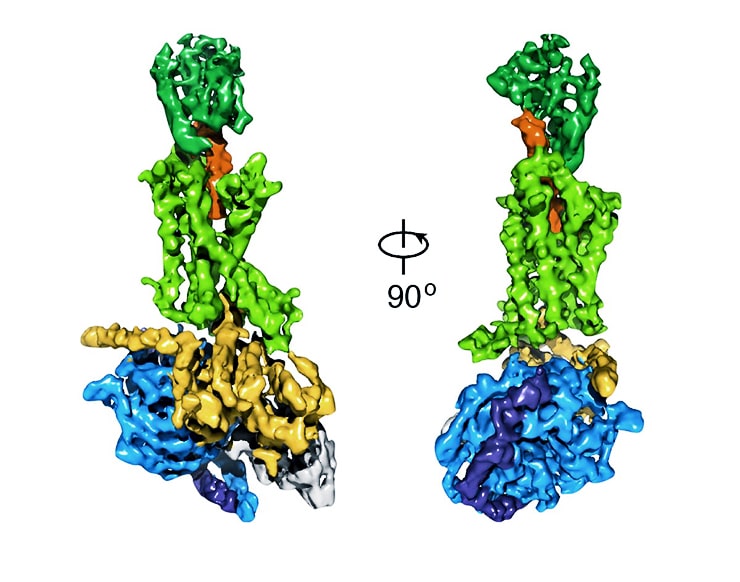

Researchers have captured the first cryo-electron microscopy images of a key cellular receptor for diabetes in action.

The findings, published in Nature, reveal new information about workings of G protein-coupled receptors—which are intermediaries for molecular messages related to nearly every function within the human body.

G protein-coupled receptors, often shorthanded as GPCRs, reside in the membrane of cells, where they detect signals from outside of the cell and convey them to the inside to be acted upon. They respond to signals including sensory input like light, taste, and smell, as well as to hormones and neurotransmitters.

The new, near atomic-resolution images provide an incredibly detailed look at how these important receptors bind to and transmit signals from peptide hormones.

The team revealed how the hormone GLP-1 (Glucagon-like peptide-1) binds to its receptor on the outside of a cell, and how this causes changes to the arrangement of the part extending into the cell—which then engages and activates the G protein.

GLP-1 plays an important role in regulating insulin secretion, carbohydrate metabolism, and appetite. It binds to the B family of G protein-coupled receptors, though information about their precise interactions have heretofore been limited by a lack of images of the complex in action.

“It’s hard to overstate the importance of G protein-coupled receptors,” says Georgios Skiniotis, a researcher at the University of Michigan Life Sciences Institute and Medical School and a senior author of the study. “GPCRs are targeted by about half of all drugs, and getting such structures by cryo-electron microscopy will be crucial for further drug discovery efforts. The GLP-1 receptor is an important drug target for type 2 diabetes and obesity.”

Diabetes could cause up to 12% of US deaths

The size and fragility of GPCR complexes have made them notoriously difficult to capture using the longtime gold-standard of imaging: X-ray crystallography. It took Brian Kobilka, a professor of molecular and cellular physiology at Stanford University Medical School and a senior collaborator on the paper, many years to obtain the first one—which led to a Nobel Prize for Kobilka in 2012.

The current study was done using a cryo-electron microscopy, or cryo-EM. Cryo-EM is an evolving, cutting-edge imaging technology that involves freezing proteins in a thin layer of solution and then bouncing electrons off of them to reveal their shape. Because the frozen proteins are oriented every which way, computer software can later combine the thousands of individual snapshots into a 3D picture at near-atomic resolution.

Advances in cryo-EM now make it possible to capture protein complexes with similar resolution to X-ray crystallography, without having to force the proteins into neat, orderly crystals—which limits the variety of arrangements and interactions that are possible.

Team maps Zika virus and finds unique ‘targets’

“Using cryo-EM, we can also uncover more information about how GPCRs flex and move,” says Yan Zhang, a postdoctoral researcher in Skiniotis’ lab and a co-lead author of the paper. “And we can observe functional changes in complexes that are difficult, if not impossible, to crystallize.”

Grants from the National Institutes of Health supported the work. Additional study authors are from the University of Michigan, ConfometRx, and Stanford University.

Source: University of Michigan